![]() thecynicalromantic

thecynicalromantic

10/20/2013

![]()

Originally posted at http://bloodygranuaile.livejournal.com/36083.html.

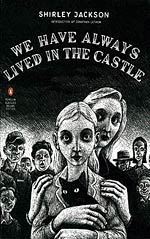

Much like everyone else who has gone through the American school system in the past few decades, I have read Shirley Jackson's famously creepy short story, The Lottery. I think The Lottery is one of those pieces that I had to read multiple times at different grade levels; however, I had never read anything else by Shirley Jackson, until now. In honor of it being Halloween, the latest book for my Classics book club was We Have Always Lived in the Castle, a short but exquisitely creepy novel about the last living members of a wealthy family, who live in a big house overlooking a small New England village.

Our narratrix in this novel is Mary Katherine Blackwood, generally known as Merricat, who is eighteen years old. The other two remaining members of her family are her older sister Constance, and her Uncle Julian. Uncle Julian is very sickly, having survived the poisoning that killed the rest of the family six years earlier. We discover, eventually, that Constance and Merricat were the only family members not poisoned, Constance because the poison was in the sugar, which she never used, and Merricat because she had been sent to her room without dinner.

When the story opens, the three of them have adapted to a very regimented and quiet life within the big Blackwood house. Merricat is the only one whoever leaves the property, going down to the village to shop on Tuesdays and Fridays. Merricat is also in charge of security, ensuring there are no holes in the fence keeping everyone else off their land, and performing a lot of odd magic rituals, mostly consisting of burying things, but sometimes including other superstitions such as breaking glass, nailing stuff to trees, and avoiding certain words. Merricat is a bit of an odd person, and her narration comes off as particularly odd because she is so matter-of-fact about things like her magic rituals, and her imaginings about living on the moon, and wishing people dead, which she does quite frequently. Constance never, ever leaves the property, or even goes into the front yard, sticking entirely inside the house and in its back gardens. This is because it was Constance who was accused, and then acquitted, of the poisoning of her family. Even though she was acquitted, most people still think Constance did it. (She didn't.)

Merricat, Constance, and Uncle Julian's idyllic and highly ritualized existence is interrupted by the arrival of their cousin Charles, who, as far as Merricat is concerned, disrupts everything. She continually refers to him as a ghost and a demon, and believes that he was able to enter the house because one of her magics failed, and she keeps attempting to do more magic to get him to leave. Charles is basically a normal guy, in all of the ways that cause him to be the most disruptive and displacing possible element in their household. In addition to taking up much of their father's space (such as staying in his room and going through his things), Charles smokes constantly, gets angry at Merricat for burying things, is generally loud, and is somewhat obsessed with the amount of money they have in the house—mostly in the safe, but he also gets extremely agitated when he discovers that Merricat once buried a handful of silver dollars in the lawn. He gets angry at the general weirdness of the household, a lot, but refuses to leave, being committed to saving them from themselves and, rather transparently, to acquiring their money. Eventually, being essentially a symbol of great big messy dudely oafishness, he leaves his lit pipe unattended, and Merricat throws it into a wastepaper basket, which causes a fire. The fire succeeds in getting Charles out of the house, but not before the firemen show up, Uncle Julian dies, half the house burns down, and the townsfolk gleefully trash most of what is left.

Constance and Merricat, being proud and weird and now deeply regretting letting anybody into their sanctuary, retreat even further, building an even stranger and more secluded life within the two remaining rooms of the house, the kitchen and Uncle Julian's room. The townspeople start leaving food at their door, apparently in penance for having trashed the place, and possibly because they seem to think that anyone strange enough to live in half a burned-down house is probably a witch or something, and, as far as Merricat is concerned, they are very happy.

Much of the creepiness in this story comes from Merricat's bizarre narration, particularly once you begin to suspect—and finally find out—that it was actually Merricat who poisoned everyone, back when she was only twelve years old. Merricat is willful, stubborn, somewhat narcissistic, and will absolutely not have anything other than exactly as she would have it; at the same time, she is very disciplined, adhering to a long list of things that she is and is not allowed to do, plus engaging in endless rounds of exacting magic rituals. It's never really clear if the magic is real or just something Merricat believes in. It's also somewhat unclear if everyone else is quite as terrible as Merricat believes or if Merricat is just a really hostile person, especially when you consider that she is the sort of person who murdered almost her entire family for sending her to her room, but it's very easy to believe her observations of people and generally be on her "side."

While this book avoids many of the goofier elements that characterize so much Gothic fiction—and I say this as someone who adores Gothic fiction—it still fits itself firmly within the Gothic tradition, both by being extremely creepy and by focusing on very dark themes such as death and destruction and the decline of very rich families. Unlike most traditional Gothics, it is short and very tightly written, avoiding both sentimentality and overwrought vocabulary. The degree to which anything supernatural happens is unclear, being either little or none at all. There is also surprisingly little violence, but a heavy focus on domesticity and domestic ritual, particularly food. (Constance does all of the cooking; Merricat is "not allowed.")

Constance, to me, is the most interesting character; while Merricat clearly adores Constance, Merricat is also 100% certain that she knows how they both best should live, and actively sabotages any attempts Constance might seem to be considering making to their lives. Merricat does not want Constance to go out into the village, which means, in practice, that she does not want Constance to stop being afraid to go out into the village. When Charles shows up and Constance starts having thoughts that perhaps Uncle Julian should be in a hospital and Merricat should be in school and Constance should leave the house ever, Merricat sees this as Charles' demonic influence and redoubles her efforts to get him out of the house, and to show Constance that they ought to stay in the house. Merricat, in short, molds both of their lives to Merricat's specific preferences, and rather than wondering for a minute if Constance is okay with that, seeks to make Constance okay with that, by proving that all the alternatives are intolerable mistakes. Merricat doesn't seem to be aware of how manipulative and possessive she is, and seems to honestly believe that she is looking out for her sister. The book ends with Merricat telling Constance how happy they both are.

Charles is probably somewhat unfairly maligned in the story, seeing as he is a regular person and Merricat insists upon referring to him as a ghost and a demon; however, I admit that even without Merricat's opinions, I really didn't like him either; he falls into the role of Man of the House very easily, even though he is just a guest, and he makes no effort to try and figure out why they are so weird or what the culture of the house is, and as far as I am concerned that makes him rude and presumptuous.

The creepiest part of the book, I think, is how hard it is not to like Merricat, to sympathize with her and agree that all the people she thinks are terrible are terrible, and that they are being small-minded and rude for being hostile to her and Constance, and that it makes perfect sense to try and protect your house with magic and anyone who gets mad at you just because they don't get it clearly deserves a bit of shaking up anyhow, and that it's really invasive of people not to leave them alone all shut up in their weird house. Being able to make the reader sympathize with a murderer—and not any sort of tragic-backstory of justifiable-homicide sort of murderer; just the cold-blooded murder of her whole family, for petty and objectively stupid reasons—is evidence of the disturbing sort of genius of really, really great writers.

http://bloodygranuaile.livejournal.com