![]() Rhondak101

Rhondak101

1/30/2014

![]()

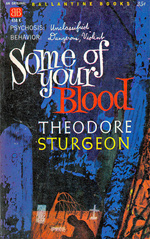

While I was reading Some of Your Blood, I was wishing that I could have read it when it was published. Since it was published in 1961 (before I was born), I then regretted that I could not come to the novella without knowing anything about it. So, if you know nothing about this book, stop reading this review now. Go read the book (I recommend it). Don't read the blurb on WWE, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or the back of the book itself. I promise I won't tell you about Rosebud either. The rest of you: scroll down.

For those of us who have read book or at least the blurb on the back of the book, it is "Theodore Sturgeon's dark and foreboding look at the vampire myth." But more than that, the book demonstrates a very interesting use of an unreliable narrator, one that rivals some of the best in my opinion, Frank Cauldhame in Iain Banks' The Wasp Factory and Alex in Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange. Each of these books made me want to re-read the book immediately, armed with my new knowledge. Sturgeon, however, does something very smart to forestall this desire, which I will explain below, but first a bit about the plot.

This is an epistolary novella that explores the committal of a solider, George Smith, to a military psychiatric hospital. (George Smith is not the patient's name, but the name he gives himself and the one others use for him.) George is placed in the hospital because he struck a superior officer. Why he became enraged over the simple question the officer asked is the central point of the story.

The novella opens with a second person address. You are told to visit the home of Dr. Philip Outerbridge and locate a secret file, "George Smith." You find it and are invited to read it. The file contains mostly the correspondence of Dr Outerbridge and his superior officer, Col. Albert Williams. The largest document in the file is the autobiography written by George while in the hospital. This document dominates the first half of the novella. It tells about George's life in rural Kentucky, his sick mother, his abusive father, and the ways he escapes that life. It tells of his time in a boy's detention home and his time living with his aunt and uncle in Virginia. However, as with all unreliable narrators, George omits some things and glosses over others.

The later half of the novella contains the majority of the correspondence and more importantly, transcripts or summaries of Dr. Outerbridge's sessions with George. This is where Sturgeon is inventive. He allows us to tag along with Dr. Outerbridge. He points out to us places in George's narrative that were bothersome to us as we read, but we did not really question them because we want to believe George. We have sympathy for George. Dr. Outerbridge re-reads George's narrative for us/with us and fills in the troublesome gaps. The way that Dr. Outerbridge solves the puzzle of George is reminiscent Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, in which the detective Hercule Poirot, provides a close reading of a document to catch the murderer. Stylistically, this novella seems modern as does the plot, which I found surprising. Today with many of us receiving imaginary degrees in profiling and crime scene investigation via TV shows, it is easy to feel a bit jaded when reading older crime novels, especially those that explore the psychology of the criminal. Yet, in this case, Sturgeon's psychology, although heavily Freudian, holds up well. The work of Alfred Kinsey, Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Sándor Ferenczi all inform Dr. Outerbridge's diagnosis.

One critique that many offer about the novella is that George is too good a writer to be a backwoods Kentuckian who didn't get much education until it was forced upon him during his time in youth detention. Sturgeon creates a voice for George that sounds somewhat authentic, but he does not trick up the narrative with phonetic spellings or too many dialect forms that impede meaning or slow down reading. I was glad of that because I often find dialect extremely annoying. While George's style is probably too rhetorical for his education or experience, Sturgeon attempts to justify stark the difference between the writing George and the written George who Dr. Outerbridge describes by discussing his alexia (the inability to use the spoken word). I respect Sturgeon's attempt. It is much better than just ignoring the difference, but I also believe that we should not quibble too much about this. The book only works because the readers care about George, and the only way to make the readers care is through George's narrative, which must be rhetorical and clear to be effective.

While the ideal reader for this novella should know nothing about it, it still works for those of us who know too much. It works because of the artful way that Sturgeon portrays George thorough his own words and the skillful way that Dr. Outerbridge deconstructs those words. I was pleasantly surprised by this work. The only other Sturgeon that I've tried to read is More Than Human. I've started it several times and stopped because I find the plot so depressing. I don't think this book will make me try that novel again, but it has encouraged me to try another book by him.