![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

10/4/2014

![]()

I've a weakness for friendly robot stories, perhaps in the way that some people have a weakness for boy-and-his-dog stories. They usually lack substance, but there is something comforting about these facsimile friendships that usually result in personal growth for the protagonist. As much as we hate to admit it, dogs and robots are dumb beyond their roles, unable to demonstrate intellectual creativity or self-motivated improvement, yet human owners project human qualities onto both beasts, for whatever reasons. Both robot and dog represent unwavering devotion and love, unlike those annoying human relationships where support and interest waxes and wanes unpredictably. Dogs and robots can be taken for granted and they never resent it. Their constancy is comforting and safe. (Until rabies or the singularity happens, in which case you're screwed).

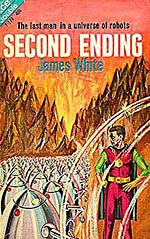

That constancy is tested in James White's 1962 robot novel Second Ending, in which robots serve their master for millennia, even beyond their own sapient evolution. The protagonist, Ross, awakens from Deep Sleep in an underground chamber nearly 300 years after he was placed in suspended animation to postpone his death from disease. To his distress, he learns that every human on Earth is dead due to the ravages of disease and nuclear fallout, and the legacy of civilization has been carried on by a troop of hospital robots. Ross is the last human alive, but with Deep Sleep and a battalion of robots at his command, he's got eternity to heal the Earth and repopulate humanity.

Second Ending is as prosaic as they come, with its linear storytelling and connect-the-dot sentences. There's nothing artful or literary about it, and it feels more fifties than most fifties novels (this was first serialized in '61, mind you). That, and an amateurish glint in his prose, may be why it took me all of a week to stay awake long enough to read its meager 100 pages. White's style is probably exactly what most people expect when they think of "vintage SF." (Which is far from the truth for many of the "old books" I read.)

Along with this stereotypical style, our hero Ross, with his plastiform toga (his clothes did not survive 300+ years), is also a stereotypical male lead. Similar to many mid-20th male protagonists, Ross is a rational problem solver, unrealistically knowledgeable in many fields of sciences, who exhibits occasional violent outbursts when he doesn't get what he wants. He makes demands, shouts orders, and he doesn't exactly balk when the bots salute him like an emperor. At one point, he takes a sledgehammer to an infuriating robot, although he does feel "sorry" when his orders result in the mid-air destruction of two near-sentient robots. He spends the rest of Earth's life cycle alone, entering and exiting Deep Sleep, but his depressing circumstances never keep him down. He's too tough for that. "Maybe he wallowed in a little self-pity, but not much nor for very long. He did some positive thinking as well" (p. 85).

The similar premise to Futurama might have readers hoping for some cigar-chewing, profanity-laced robot moments, but the bots in Second Ending are more like Rosie from The Jetsons, rather than Bender (despite my unrealistic hopes for the latter). They tick, they request orders, they don't divert from their programming until... until they spark their own little singularity event and become the intelligent designers of a new human race. They never tell Ross about their cyber enlightenment, but they keep him in Deep Sleep for millions of years, with occasional awakenings just to study him and prepare him, while they explore deep space, dabble in genetics, and steer the evolution of a similar humanoid species — just to give Ross the companions for which he yearns. (A dog could never do that.) Both Ross and the reader are in the dark about this development until the last few pages, but the robots' endearing initiative overshadows Ross' annoying macho attributes.

And that's why this story is compelling, despite its lackluster style. The mind is stretched to imagine both the evolutionary feats accomplished by the bots, as well as the immense spans of time they experience. It's dull, dry, and scientifically dubious, but this man-and-his-robot story is heart-warming and imaginative at its core.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com