![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

8/3/2016

![]()

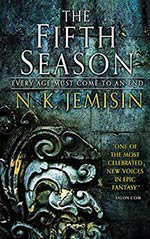

Based on reviewer response so far, I expected this to be like City of Stairs, by which I mean it would be very popular within its subgenre, stir the passions of many a blogger friend, but have very little effect on me. Between last year's insipid The Goblin Emperor and this year's heft of shortlisted fantasy, it's time I admit the unforeseen and reluctant truth that I'm just a sci-fi/realism reader now.

But it's hard for even a fantasy detractor like me to not recognize good, solid fantasy when I see it.

Some might argue that the big reveal of The Fifth Season is that it is actually science fiction, not fantasy, and they would be correct insofar that our not-so-far future reality converges on Jemisin's far-future cracked earth of instability and hierarchies. At a later point in the novel, the secondary twang is exposed for the primary reality that it is, and we find ourselves following what is actually a post-apocalyptic tale with the only thing epic being the extent of climate disaster. But even though it is technically more sci-fi than fantasy, the feel of fantasy just can't be shaken off. (And we know so much of sci-fi is fantasy anyway, so.)

And I know, I know... these distinctions don't really matter, but that's the only reason I can think of why it didn't quite connect with me. It is a very good story, for sure, and I probably would have adored it in my early days of exploring the subgenre.

For readers with a similar bias, The Fifth Season is still worth exploring. Sure, it still relies on those fantasy signatures that try my patience: hefty world-building, magic systems with arbitrary rules, and endless travelling to show off the world-building (and so you never know when you're nearing the middle or the end, and makes you wonder why you can't just drop in at the 70% mark and force-absorb the details for a possibly less passive experience). But it also includes these neat little interactive moments that invoke other powerful moments in SF and literary history: a Dune moment with the hand test; a Kindred moment with Alabaster's apologism; a Beloved moment with the horrifically understandable emancipation of the child. By engaging with these moments, TFS inserts itself into a higher class of SF, touching upon real human issues by honestly and modernly engaging some of the most uncomfortable moments in literature in the way a jaded SF reader would respond and understand (and squirm). Granted, it isn't immune to movie contract bait like over-heightened and pithy dialogue ("I'm not interested in your rusting history --" "History is always relevant."), and there are also too many moments when sluggish description muddles up the mind's eye during action scenes, including the narrative's overreliance on "suddens" and "suddenlys" stalls the prose when just stating the action would be sufficient, but that happens in sci-fi, too.

All of that feels like nitpicking when considering the conceptual framework of the novel: the worldbuilding of TFS transcends common landscape descriptions, emerging as a ground-to-sky atmosphere, pulled through into the language and structure of the story, designing a clash-and-converge system of tectonic narrative threads. The use of slang, with all its "rusteds" and "Earth's sakes" and "Earth, be damneds," can get tiresome, but then moments of true playfulness and originality emerge: at one point, a simple comma removal gets to the actual fulcrum of the tale: "I've spent my whole life either training or working, for Earth's sake," and serves to illustrate the nature of this dry and cracking world derisively called "Father" Earth.

Also worth discussing is the use of second-person perspective throughout one of the threads. Usually relied on as a horror gimmick or solution to literary boredom, the first sign of this might induce eye-rolling, but it's put to good use here. In a thread that depicts the very fresh shock of a grieving mother, first-person would be too unconvincingly verbal to effectively convey the PTSD, while third-person might be too distant to effectively grasp. The immediacy of the "You" forces the reader to internalize that sense of shock and gives that poor character a chance to retreat inward.

These are mostly technical comments and barely scratch the surface of what is a highly original secondary/primary fantasy world of metaphor, with touches of experimental slave narrative, as well as spurring meditations on sex, politics, motherhood, and the body; some subtle, some not so -- as it should be. It's still really not my thing, but it's leaps beyond the trite and mediocre fantasy of last year's Hugo ballot, and the passion surrounding it is valid, if beyond my full appreciation. Highly recommended for fantasy fans, even if newly-hatched, as they inevitably walk toward the elves and dwarves section of the library (as long as they are mature enough to handle the idea of threesomes).

(I do hope Jemisin will eventually skip out on the fantasy world and test her hand at some kind of surreal realism, because there's a grim undercurrent, as well as a curiosity about people, that's present in her storytelling, and comes off as too constrained in this imaginary mode.)

Snatch if you're a fantasy lover. Avoid if you despise that perniciousB-52's earworm classic "Love Shack" because it'll follow you around for the entire week after. Tin roof! Rusted!

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com