![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

9/11/2016

![]()

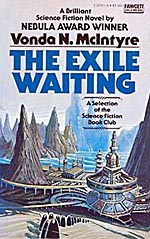

Disorienting and blurry, the subterranean world of Vonda McIntyre's The Exile Waiting (1975) hosts a confusion of social structures that aren't easily deciphered. The first few chapters are especially complicated as the first act winds its way through a series of tunnels and bends and broken thoughts as Mischa resists Gemmi's empathic tugs, rescues a self-destructive Chris, and observes the so-called normalcy of this alien place called Center. Disjointed journal excerpts by an outsider named Jan intensify the narrative haze.

Center is a strange place. Unfamiliar in the ways it defies present-world logic (hired beggars; dormant political and mechanical power systems in some places, active in others; nuclear-crystal alchemy) and familiar in the ways it employs standard sci-fi tropes (telepathic communication, dog-eat-dog dystopia, pernicious underboob cleavage), but all of those odd details add up to a cohesive and thought-provoking framework from which McIntyre hangs her complex and many-tendriled tale. The claustrophobic and oppressive atmosphere is intertwined in each theme, where a potent mix of ageism, lookism, ableism, and toxic family systems has the potential to drag each character down into a self-hating pit of inaction. Some succumb; some overcome.

Welcome to post-nuclear holocaust Earth.

McIntyre doesn't spoil this right away-- the book jacket does; I was too hasty to notice-- so it seems engineered for groping in the dark as readers are dropped into the center of Center from page one, reminding me much of one of my other favorites, Daniel Galouye's 1961 forgotten classic and Platonic allegory, Dark Universe, where the premise of darkness and blindness is gradually illuminated as an underground bunker (though McIntyre's is better written and far more progressive in its gender politics). From Verne to Jemisin, SF sometimes likes to ditch the outer limits of space in order to excavate Earth's underground for adventure and meaning, but McIntyre leaves no rock unturned, employing every element of her underworld to trap, reflect, deflect, and echo the complications of the story, as well as the complications of life-as-we-know-it and life-as-we-soon-might-know-it-gods-forbid.

Modern readers will most likely notice and be impressed by McIntyre's treatment of gender, employing techniques considered original by today's writings stars. Placing women in traditional male roles (navigators, guards, administrators etc) is nice, if not surprising (and kinda Gaddafi-ish in a way the way they're often sexified), but the way each character is introduced by occupation, thereby delaying the use of gendered pronouns, is refreshingly troublesome to default thinking patterns, bringing to mind recent fan favorite Ancillary Justice. McIntyre wants to disrupt your reading flow:

The steward reached for Mischa, who ducked the long silver-painted fingernails and lunged into an opening between two cases of books. The guard grabbed at her and tried to hold her, but Mischa hit her wrist with the edge of her hand. The guard grunted with pain and let go. Mischa fled through a corridor and up a flight of stairs.

There are better examples of this, but drawn out much longer.

With complex bad guys, gritty anti-heroes, and lower class characters oppressing the even lower classes in order to preserve their tenuous safety nets, McIntyre conveys a reality of hard-living that's rarely seen in something best categorized as science fantasy, and all astoundingly well-drawn within 215 pages-- without the explaining, without the bloat, without extraneous dialogue dumps and day-to-day diary plots. How a novel about a spunky can-do action-femme can feel so low and grim and dreary and depleting is testament to McIntyre's ability to foster consistent atmosphere, whether in the limestone abyss of Center, the velvet plush of the Palace, or the "incredible crystal garbage dump" of nuclear waste.

But ultimately, it's about family bonds --toxic as nuclear waste in these pages-- and trying and failing and trying again to break them. It's about Mischa and Jan, soul-sibling inverses of one another: one unable to break away, the other unwilling to return home, neither quite what their respective families had in mind. Though Mischa and Jan lead their twinned tales, nearly every character with a speaking role-- good, bad, sympathetically bad, distrustingly good-- shares this sense of unbelonging unescaping, drawing every one of them deeper into the gravity well of emotional capitulation. A few break free.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com