![]() Rhondak101

Rhondak101

10/19/2014

![]()

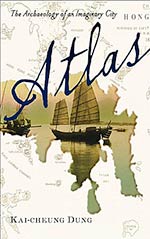

I first came across Dung Kai-cheung's Atlas: The Archaeology of an Imaginary City because it won the 2013 Science Fiction and Fantasy Translation Award. The book was written fifteen years ago, but has just now made it into English by the combined translating efforts of Anders Hansson, Bonnie S. McDougall, and the author himself. The premise of the book: In the far future a scholar (who we only know through his/her narration) is trying to understand the lost city of Hong Kong by reading its maps. Most of these maps are from the era of British colonization and possession. The book simultaneously addresses local and colonial histories, the processes of colonization, and the theories behind creating and reading maps.

The book is divided into four sections: theory, the city, streets, and signs. The first and last sections are the most scholarly. In them he uses the maps of Hong Kong to explore the politics of mapmaking and how colonial biases are clearly written into maps. In these sections, he shows his debts to post-structuralism and deconstruction. For example, he writes about the theory of displacement: "every place on a map is a displace. A place is never itself but is forever displaced by another. This is also to say that the map itself is a displacement, and cartography is such a process of displacement" (10). He continues to show how maps do not portray any kind of objective reality but strive to create a "reality" of their own.

The last section explores the parts of a map, showing what information legends, orientation, colors, topographical features contribute. Much of this section is theoretical like the first one; however, a couple of chapters venture into practice rather than theory. The narrator discusses how cartographers (in this future time) decided to use a 1997 tourist map to reconstruct Hong Kong. The result is a Disneyland-like city. A neo-tourist writes about "shopping for replicas for heritage objects from the city's past" (146). Such objects are broken plastic and metal toys, stopped pocket watches, broken electronics and the like. The neo-tourist also complains that there's no one "to play the residents" in this artificial scenario (147).

The strongest sections are the second and third which explore specifics about the names and locations on the maps. These sections are most reminiscent of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, to which this book is usually compared. These sections give slice-of-life descriptions of visitors and residents, explore the etymology of streets and locations through the lenses of linguists and folklore. My favorite describes the streets Tung Choi and Sai Yeung Choi, which mean "water spinach" and "watercress," respectively. Because water spinach is a summer crop and watercress is a winter crop, the single street had two names based on season. For that reason, "if you sent a letter to Tung Choi Street in the summertime but wrote the name Sai Yeung Choi Street by mistake, it might be winter before it got delivered" (110). This, of course, frustrated the bureaucrats and the colonial infrastructure, so two streets were created, one named Tung Choi and the other named Sai Yeung. The inhabitants, used to living on one street in the winter and another in the summer, took to moving to the street appropriate to the growing season and leaving the other one abandoned.

I wish there were more vignettes like this in the book. Unfortunately, there's much more theory than story in this book. This is not a book for everyone. Readers need to have an interest in maps and the theories of their reading and construction. Readers will be disappointed if they are looking for narration with characters and a plot. Readers will also be disappointed if they are looking for an interesting future world which is looking back at Hong Kong's maps. There's no indication at all what this world might be like. There are aspects of this book that I found fascinating and parts that I found boring. It is a mixed bag.