![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

3/13/2015

![]()

…in which a hero goes on a dreamlike journey… to find a shirt…

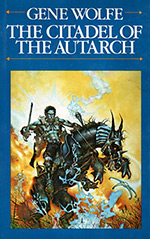

Rajan Khanna, at Lit Reactor, calls it "fractal." Peter Wright, at Ultan's Library, says "Every reading is, then, an individual resurrection." Months after completing my first reading of The Book of the New Sun tetralogy, I'm still digesting it, like a piece of shoe leather someone dared me to eat.

In an earlier comment, I called The Book of the New Sun a basic hero's journey. It is, but it isn't. It's a subverted hero's journey where the hero moves away from violence, and toward himself.

Or maybe not. Because even after four books, we really do not know Severian. He is as deceptive and misleading as he was in the beginning.

So let's say he moves away from violence and discovers a respect for life. And a shirt.

***Oh yeah, spoilers.***

***Not that it matters with this one.***

The Autarch of the Citadel

In psychology, before a behavior can be extinguished, it must burst. In The Autarch of the Citadel, our lapsed torturer finds himself in the most violent of situations: war. Much is spoken of the nature of war, and there's no doubt that Wolfe's experiences during his draft to the Korean War influence this part of the tale. "War is not a new experience; it is a new world," Severian tells us [205]. Severian is weaponless, too weak to fight, he spends a lot of time hiking around, an explosion happens, people die. Suddenly, this surreal tale feels slightly autobiographical: A young man's exposure to ultra-violence turns him away from his core beliefs about violence. Was this the point all along?

Every man fights backward--to kill others. Yet his victory comes not in the killing of others but in the killing of certain parts of himself… [166]

The pacifist message of The Book of the New Sun (which doesn't feel very pacifist until the final novel) serves a grander theme, something more akin to that of Wolfe's faith. From its allusions to its archetypes to its overall arc, The Book of the New Sun drips with Catholic symbolism. Like the biblical tale of Adam and Eve, Wolfe begins his story with a naked (shirtless) manboy. Throughout the journey, Severian forgets about his bare skin (and so does the reader; Wolfe is very good at causing the reader forget things), and Severian only becomes aware of his nakedness when questioned later, by a young boy (also named Severian).

I used to wear a shirt… But, yes, I supposed I am a little like that, because I never thought of it, even when I was very cold. [98, The Sword of the Lictor]

This conversation, prompted by a discussion about the nature of zoanthropes (humans who become beasts) and alzabos (beasts who take on the characteristics of their human prey) says much much much about Wolfe's thoughts on human nature, and introduces some of the most ingenious concepts in the entire tetralology. But, this is about Severian. This is about faith. And Severian's entire development can be whittled down to this very basic, Catholic-inspired metaphors of nakedness and sin.

Severian has several earlier moments of enlightenment (particularly when it comes to chopping off the heads of beautiful women) but his turning point is not due to his love for Thecla, not his pardon of Agia, yet well before his loss of Terminus Est. Severian cannot change until he becomes aware of his nakedness. He covers himself in the final book, he shuns his violent career for good.

The Language

Wolfe adopts arcane terms from ancient Latin and Greek to name new things in his narrative. Not considering the incredible amount of work and intellect required of Wolfe to design this new vocabulary, it is essentially a typical sci-fi stunt. I've seen SF gurus call it "The Gauntlet," and it can make or break a sci-fi reader.

Gary K. Wolfe (no relation) a few months back alluded to this gauntlet on the Coode Street Podcast, suggesting that modern readers treat hard SF vocabulary as "just part of the prose" (this is a paraphrase, probably) and overlook most of the unfamiliar words. Habitual SF readers learn to not fret over unfamiliar terms and the narrative eventually presents itself through context. The Book of the New Sun, despite its entertaining and detailed Appendices, should be read no differently.

So, "autarch," "fiacre," "peltast." Not important. You'll get it if you need to. (If he's sitting on it and it moves, it's probably a horse-like beast of some sort.)

What does matter is the density of the prose, and, more specifically, the dialogue. And why it changes between the second and third book.

Example from the end of the first novel:

"Lords," he said. "O lords and mistresses of creation, silken-capped, silken-haired women, and man commanding empires and the armies of the F-f-foemen of our Ph-ph-photosphere! Tower strong as stone is strong, strong as the o-o-oak that puts forth leaves new after the fire! And my master, dark master, death's victory, viceroy over the n-night! Long I signed on the silver-sailed ships, the hundred-masted whose masts reached out to touch the st-st-stars, I, floating among their shining jibs with the Peliades burning beyond the top-royal sp-sp-spar, but never have I see ought like you!..." The final chapter of the first book, The Shadow of the Torturer

Example from the beginning of the third novel:

"It was in my hair, Severian," Dorcas said. "So I stood under the waterfall in the hot stone room--I don't know if the men's side is arranged in the same way. And every time I stepped out, I could hear them talking about me. They called you the black butcher, and other things I don't want to tell you about." The opening paragraph of the third book, The Sword of the Lictor. The exact halfway point of the series.

Dialogue in the first two novels is dense, arcane, ambiguous whereas the dialogue of the last two novels is direct (at least in words, if not in meaning) and colloquial. It suggests an end to much of the dreamlike meandering and a return to reality. And, whadayaknow, Severian happens to be in the place where he was headed in the first place. Were the previous adventures complete follies?

But the Women

Severian is a flawed and unreliable narrator who blatantly lies about his eidetic memory. His portrayals of the women in his life are bound to be influenced by his limited and manipulative POV. Naturally, Severian's recollection of these women will be flat in personality BUT NOT FLAT IN THE BOOB AREA BECAUSE MAN, JOLENTA'S ARE LIKE THE SIZE OF HIS HEAD. So he tells us.

So female readers, and allies who are equally put off by sexualized female characters, can be comforted by the fact the we don't really know these women who enter Severian's life, and they may not actually be as dull, ditzy, manipulative, needy, and carnal as Severian describes them. And, anyway, those traits may be the only way women can survive in this Dying Earth setting.

But, no.

It's too much. It's too much pointless sexualizing. Too much pointless tussling with the crazy women. What is the point of Jolenta? What is the point of Agia? Do they really serve the structure in the best way possible?

I'm not convinced, and I may be reacting to my natural discomfort from reading about female characters who hike around with thighs so thick they cannot walk, and with dresses torn just so the breast can flop out. (This did not feel like intentional mocking of the fantasy subgenre.)

Wolfe, to his credit, selected the best devices to expose his problematic worldview, without having to accept much flack for that worldview. Chris Gerwel, at A Dribble of Ink, sheds more light on Wolfe's personal gender problems with more authority than I have, and his conclusions lend credence to my personal reaction to these female depictions. Despite Severian's sucky worldview, Wolfe's hand is visible here. His deterministic influence is palpable. And icky.

But Skillz, Man!

Gene Wolfe is an intentional and subversive writer. His plot is the structure, and the structure reveals the real story. He drafts and redrafts, he layers and threads. He has a sixth sense about readers; he knows what we will overlook during the first pass, and he knows how and where to hide things. Obfuscation is his game, and it's impressive.

But do I care? A faith-based morality story with sexualized female characters is still a faith-based morality story with sexualized female characters, with or without the linguistic and narrative manipulations. So what if he weaves words the way a wizard weaves spells?

I'm going to set aside these thoughts for a couple of years, and do a reread before I read the Coda, Urth of the New Sun (1987). Maybe that tasteless shoe leather will be fully digested by then, and I will have absorbed more of its magical, literary nutrients.

That would be like saying that the writing in this book, over which I have labored for so many watches, will vanish into a blur of vermilion when I close it for the last time… [162]

Oh, Gene… go cover yourself.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com