![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

5/28/2015

![]()

'I've not gotten what news God or Ian Sparling now have.' Her reference wasn't theological; Goddard Hanshaw was the mayor (p. 28).

A sidesplitting line, not standard in this page-light, philosophically-laden extra-planetary romance, but deserving enough to get top-billing by me. Perhaps a sign of what Anderson could be if he ditched the political romance for more satire; maybe his slim novels would be better appreciated by new SF fans.

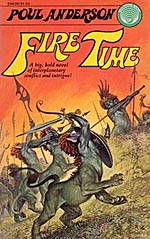

But Fire Time holds itself together better than the overreaching, underpaginated People of the Wind, or the galumphing The High Crusade (an ideal playground for satire, but the humor fails in its puerile simplicity). Another space yarn with parallels to Earthen conflicts, fodder for typical Andersonian commentary on ideological conflict, shared territory, and humanism.

Anderson takes us to the planet Ishtar, where the lands are blazed every thousand years by "the demon star," one of its three suns. Fire time is coming to the two peoples who inhabit this world, including the long-lived, highly evolved Ishtarans, lion-like in appearance, but covered in plant growth instead of fur. Diplomats from Earth attempt to press their own will on the territorial conflicts of these peoples, and the planet falls into diplomatic instability and territorial uncertainty.

The back blurb is a gauntlet of its own, never fully resolved within the text, so readers must adapt to the unexplained star slang of this planet (or Google it, as I did). "The Demon Sun," "The Red One," "The Stormkindler," "The True Sun," and "The Invader" are all terms the reader is slapped with upon opening to the first pages, but all one needs to understand is that Fire Time is about to happen, and it sucks.

Commenter Randolph has pointed out Anderson's conservative nature, which perhaps I've missed as I've only read his thinly-veiled allegories of the Israel-Palestinian conflict, where Anderson's illustrative attempts at humanizing and rationalizing both sides of his alien conflicts feel more peacenik than warmongering.

But as I look again at my underlinings, I see a common theme:

Intellectuals hate to admit that beings who have wars and taboos and the rest can be further evolved than their own noble selves, who obviously have none (p. 25).

Barbarians--yes, barbarians--could win against civilization only by default, when it was breaking down (p. 9).

Nobody starves in the Backworld, as nobody does in Welfare. But aid is a mere stopgap, and still taxpayers feel drained...

...Birth control? You can't ask entire peoples to make themselves extinct. Redistribution of wealth? The conservation laws hold as true in economics as in physics. Return to a simple and natural existence? A precondition is the death of 90 per cent of the human race.

(But the stars remain. And given an ideal, the capital necessary to make a new beginning will somehow come forth. If a man has no other capital, there are his two hands.) (p. 74).

The only security between peoples is common interest (p. 83).

So Anderson is a bootstraps kind of guy, with lots of conservative rhetoric. But that can't be--this was nominated for a Hugo. Conservatives never get nominated for Hugos.

But conservative or not, it's not the political romance but the personal romance that will hook readers. Ian and Jill, theirs is a love spurned by the generation gap and Ian's stale marriage, but it's not enough to dampen their chemistry. But, typical in all sensitive diplomatic conflicts, Ian and Jill wind up as hostages together, and the not-so-barbarian enemy combatants allow our age-crossed lovers to share their comfy, bedded prisons and take unsupervised walks in the jungle. Nothing sexier than a hostage crisis.

(I'm making fun of the romantic subplot, but it hooked me. This is also where more of Anderson's less traditional social values shine through.)

*spoiler* *you're not going to read this anyway* Ultimately, the Anderson I'm familiar with shines through, where diplomacy and cunning win out over brute force, although the characters do partake in some mild risk-taking and a quirky bit of double-crossing (then un-double-crossing) at the end. And maybe it ends with some threesome hand-holding among frenemies.

Interestingly, this novel is dedicated to Hal Clement, the man who brought us the Hard SF novel-that-should-really-be-a-textbook Mission of Gravity (1953), which may explain why this novel feels richer than the previous two Anderson's I've read. MoG is quite dull, but perhaps the inspiration of Clement's efforts to build a more scientifically-realized settings resulted in Anderson's engagement of better detail to develop the experience of Ishtar. Combine that detail with Anderson's penchant for humanist romance, and we get a story that's slim and interesting, but I'd like to think there's a better Anderson out there. Tau Zero (1970) may need to come next.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com