![]() jynnantonnyx

jynnantonnyx

3/27/2010

![]()

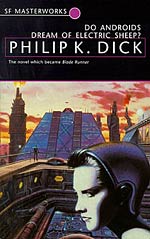

Like all of Philip K. Dick's novels, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a strange blend of reality and unreality. It has been a full month since I finished reading the novel, and I've put off writing a review because it's hard to know what to say about it. The basic plot of the book, which survived mostly intact in the film adaptation Blade Runner, has as its protagonist Rick Deckard, a bounty hunter who hunts androids, robotic beings who are indistinguishable from humans except for their total lack of empathy. The lead bounty hunter has been taken down by an android, and this is Deckard's chance to make some money he desperately needs. He proceeds to pick off the androids one by one, and the story ends when his task is complete. Ridley Scott's film used this plot as a vehicle for dystopian and weirdly demonic imagery, and to create a film noir-like mood. Dick uses it like he usually does, as a tool for examining the tension between reality and fantasy.

The very first sentence of the book describes a "merry little surge of electricity piped... from the mood organ." The mood organ is a tool for controlling emotions, and is a much-desired commodity in a world that is barely surviving after a nuclear catastrophe. If you don't want to wake up in the morning, the organ can make you glad to be awake. If you are depressed, the organ can fill you with bliss. It has the effects of mood-altering drugs without (apparently) any unwanted physical side effects. The other machine which plays a large role in the novel is the empathy box, which is used primarily by followers of a religion called Mercerism as a way of sharing emotions and images with other people who are using the box at the same time. Both machines, notably, are tools for escaping interaction with reality.

And reality in the future of Androids is indeed bleak. The nuclear wars have irradiated much of the world, leading to genetic disintegration, mass animal extinctions, and popular immigration movements off-planet to Mars. Animal husbandry is considered a civic duty for those who can afford it, and a moral duty for followers of Mercerism. Those who cannot afford a real animal buy cheaper robotic "electric" models. The skies are always discolored, entire swaths of continents are wastelands, and ambient radiation transforms intelligent people into "chickenheads" by rotting their brains. The androids of the novel are not the wonder-experiencing replicants of the film; they are harsh and uncaring, empathizing not even with the death of one of their own. It is no wonder that the inhabitants of Earth escape reality through mood alterations and hallucinogens. Likewise, even the inhabitants of the supposedly nicer Mars seek an escape through the fantastic, adventurous science fiction novels of the past—one thinks of the novels of E. E. "Doc" Smith—because the reality of their situation is hardly like it appeared on the travel ads.

Deckard's final triumph is a mixed one. Strange things happen with Mercerism and a vision Deckard has of its supposed founder. Likewise, his path intersects with an animal in such a way that leads to a brave act of acceptance of reality. Reality in this novel, as in all of Dick's novels, is hard, but still worth pursuing for its own sake. The truth is its own reward, despite its difficulties.

http://blog.worldswithoutend.com/2010/03/do-androids-dream-of-electric-sheep/