![]() thecynicalromantic

thecynicalromantic

7/17/2015

![]()

When I heard N.K. Jemisin speak at Arisia, she mentioned that she had written her Dreamblood duology before the Inheritance trilogy, but hadn't been able to sell it. She gave two reasons for this: one, that it was "too weird," and two, that there weren't any white people in it.

To the second point, I say: There were so white people in it! There were two; they both died tragically for plot-furthering reasons in the first 10% of the book. That counts, right?

Anyway. Now that that's out of my system, on to the first objection: the weirdness.

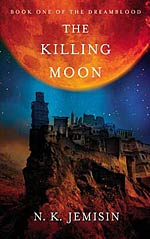

Yes, The Killing Moon is weird. It's very weird. And I loved it for its weirdness. It's thoroughly imaginative and highly original, drawing from a lot of real-world mythological and religious stuff and recombining and extrapolating it into nothing remotely resembling anyone's D&D campaign. The main civilization in it, Gujaareh, is very loosely based on ancient Egypt, mainly in that it floods once a year and death is a huge part of the religion and it's in the desert. And there's some stylistic "McEgypt" flavoring, as Jemisin put it.

In this world, there are four humors in the human body: dreamblood, dreamseed, dreambile, and dreamichor. They all have magical properties if you know how to use them, and they are all secreted during dreaming.

In Gujaareh, dreaming is very serious magical and religious business. The various orders of the religion harvest these dream-humors and can do magic with them. Mostly healing. But a few priests, the most revered and important, are called Gatherers, and what they gather is dreamblood. To heretics and outsiders, they kill people. The view from inside Gujaareh is more complex: Gatherers usher people into Ina-Karekh, the land of dreams, and help them construct what I in my utter lack of Jemisinian poeticism can only describe as their "happy place," where their soul will be at peace; then they cut the cord between their soul and their body so they die peacefully. The cost for this service is merely the tithe of dreamblood.

Gujaareh faithful believe this is an awesome system; predictably, it creeps basically everyone else the fuck out. Especially when you consider that there are two ways someone can be marked to be Gathered--one is if they request it, due to injury or disease or some other pain they wish to not endure any longer; the other is if the holy orders deem them corrupt. Corruption is not tolerated in Gujaareh. Or so it is believed.

The plot of this book is about four Gatherers--well, three Gatherers and a Gatherer-Apprentice--and a badass lady diplomat from neighboring Kisua exposing a tangled web of lies, secrets, and coverups that may indicate that corruption in Gujaareh goes right to the top, and war may be right around the corner.

If that sounds all too insubstantial and shadowy and political for you, here's the fun part: They're tipped off that something is rotten in the state of not-at-all-McDenmark because there's a Reaper running around, Reaping souls. A Reaper is basically what happens when a Gatherer goes corrupt and scraps all the peace and providing a service bit of Gathering and just rips people's souls out of their bodies and eats them. It is bad times all around.

So that's all I'm going to say about the plot.

Since the magic in this system is predominantly done mentally (there are a few physical props they use, but not many) and takes place literally in dreamland, and is so heavily intertwined with religious faith, the fantasy aspect of this book and the psychological novel/character-driven aspect of the book must be closely intertwined, and Jemisin pulls it off beautifully. The characters feel real and even relatable, and very human, even as their psychologies are clearly shaped so much by these forces and powers and beliefs that we don't have in our world. This is hard to do and very impressive, I think. And it means, for me at least, that the world was able to really suck me into it, becoming rich and real-feeling without a lot of pages of scene-setting info-dumping descriptions. The language helped too--the whole book is written in a distinctly nonmodern register, although not so flowery or stylized that it slows down the way reading actual ancient texts does. Although I did end up reading a lot slower than I often do with big epic fantasy books, because I did want to stop and savor the language and think about what was going on, since it's definitely far enough off the usual beaten path of familiar fantasy tropes that I think if I'd just ripped through it the way I rip through, say, Discworld books (which are all about the familiar fantasy tropes), I'd miss a lot and get confused.

I want to talk more about the specific characters but I'm not sure how to do that in a way that's not enormously spoilery. Sunandi, the Kisua diplomat, is a great, great character--flawed, mostly by being enormously judgy of the Gujaareh religion, but smart and powerful and full of agency, and also one of the more "normal" viewpoint characters for a modern reader, probably, in that she's not an adherent of a wacky death cult. Nijiri, the Gatherer-Apprentice, is a fierce protagonist--I feel like I want to peg him as the protagonist because the storyline turns out to be a sort of terrifying coming-of-age narrative for him, and I read so many YA/coming-of-age stories that it's easy for me to latch on to seeing that as the central narrative character arc, but I think you could probably make a good case that he and Sunandi are co-protagonists. Nijiri was born servant-caste before he was taken into the priesthood and he's extremely strong-willed, which could have been a bad combination in the outside world but generally serves him well throughout this story: he refuses to give up no matter what monsters are roaming around the city or how screwed up his mentor Ehiru gets.

I feel like I'm doing an awful job talking about this book. It deserves a much more careful review than I can give now. Maybe when I finish the duology I can offer more complete and coherent thoughts on the series as a unit.

http://bloodygranuaile.livejournal.com/68089.html