![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

8/11/2015

![]()

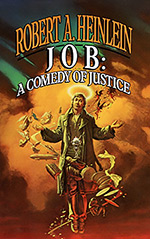

Leave it to Bob to ruin a good blasphemy story. All the parts are there: a science fiction Job, manipulated by frivolous gods who shuffle him from universe to universe, job to job, with his savvy, pagan girlfriend in tow. But Heinlein's old-fashioned, fuddy-duddy chauvinism coats this tale with dust, making it not nearly as biting or progressive as true religious criticism should be.

But let's admit it: even Joan Rivers ain't got nothin' on Bob Heinlein's grasp of female fashion. We always know what the ladies are wearing. Or not wearing, which is often the case. I'll spare you the paragraphs, for they are difficult to tailor for this post because the many musings about female dress tend to... linger.

In his defense:

Talent shmalent. You should see the stuff that gets published. But you must hike up those sex scenes; today's cash customers demand such scenes wet. Never mind that now; I didn't call you here to discuss your literary style and its shortcomings. (p. 393)

Not that the sex scenes are particularly wet in this novel. Plenty of male gaze, followed by chastely referenced bedtime tumbles.

And the suggestive incest is really just Satan talking, so that's perfectly appropriate and not at all something Heinlein might or might not be obsessed with because he doesn't seem to comprehend the most basic tenets of cognitive development research.

Worse yet, good ol' boy gags in the forms of sexism and ethnic slurs speckle this tale as comic relief-- granted, it's most often presented as a logical frame of voice for the Christian activist protagonist, yet it often flickers with the paternalistic candor of Heinlein's strong, narrative voice. It's hard to tell which is which.

If you are ever naughty enough, I may beat you. But I would never put you away.' (p. 134)

Much like the plight of his protagonist, a man at the mercy of the gods as they shuffle alternate universes like a deck of cards, this novel is yet another demonstration that the social progress of the mid-20th century befuddled this celebrated Grand Master. But perhaps we should let Mr. Heinlein speak for himself:

I think my greatest trouble with all these worrisome world changes had to do, not with economics, not with social behavior, not with technology, but simply with language, and the mores and taboos thereto. (p. 210)

Much as his fans will disagree, Mr. Heinlein was never ready for the future.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com