![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

12/7/2015

![]()

In the subgenre of "community trapped--possibly by aliens," Robert Charles Wilson has at least two entries to his credit that I know of, and his bibliography suggests more. I've speculated before that Stephen King's 2009 TV-deal-bait book Under the Dome might have been inspired by Wilson's work, perhaps to exercise some leftover ideas from The Stand(1978). It's not surprising that science fiction authors find this premise attractive with its promise of a literal microcosm, an ideal setting for a large cast full of character tensions ready to boil over.

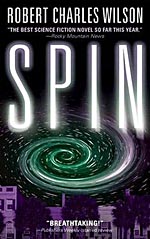

In Spin (2005), Wilson expands the claustrophobic microcosm idea, cloistering the entire Earth into his fictional bubble, while keeping the cast minimal. Spin is a reread for me, though it was so long ago, all I remember thinking afterwards is that maybe spacey science fiction isn't all that bad and perhaps I should try reading more.

At 12 years old, Tyler Dupree (and speaking of Stephen King, is this name not peculiarly similar to Shawshank's Andy Dufresne?) and friends witness the sudden quarantine of Earth when the stars abruptly blink out of the sky. It's soon discovered that a permeable membrane has encircled the planet, blocked out the solar system, and provided a simulacrum sun. Life goes on as usual, except for the growing concern that the universe outside the membrane is aging normally, but at a rate of 3 years per 1 second on the cloistered Earth. Tyler and his friends grow up as part of the traumatized 'spin generation,' and Tyler goes to work as a medical doctor on the Perihelion staff, his best friend's research and design company tasked to find new ways to combat the encroaching menace of the rapidly aging sun.

The trapped society premise, much like the locked room premise, is less about the setting, less about the rationale, and more about character interaction, which Wilson delivers with psychological aplomb, fully prepared for the direct and indirect implications of a somewhat unobtrusive cosmological horror. Psychologically sound, minus some of the aluminum tang of canned genre that taints so much of the previous thirty of years of SF, the trajectories of Tyler, Jason, and Diane bump and bounce, a human three-body problem, their divergences tied only to their individual coping mechanisms, which struggle against the inexorable pull into each other's orbits. If handled by some of the few truly talented, inter- and intrapersonally aware writers of the time, such as Ursula Le Guin, David Mitchell, or even Kim Stanley Robinson (who sometimes falls into pop psychology cookie cutter traps), this could be a richer tale. But given the genre standard, Wilson's work in this regard is head-and-maybe-a-shoulder above the rest. At least he seems to give a damn.

Most compelling is the orbital pull between Tyler and his unrequited childhood love, Diane, the most traumatized of the three, who buries her head in a religious cult in order to deal with the terror of the Hypotheticals, the may-or-may-not-be aliens controlling the membrane. But Tyler can never move on from Diane, and his thoughts and actions always drift toward her:

...who had always been restrained by forces I didn't understand: her father, Jason, the Spin. It was the Spin, I thought, that had bound us and separated us, locked us in adjoining but doorless rooms. (276)

However, readers who base the success of a book on the protagonist's growth are advised to look elsewhere. Trapped within his own cosmology, orbiting the lives of his friends, Tyler never breaks free. Much like Earth, Tyler's orbit is his fate, and only an unnatural, impersonal force could rescue him from that curse. Happy ending seekers might appreciate the conclusion of Tyler and Diane's trajectories, though I'm of the opinion that their finally-requited love is not a good thing, nobody grew, and that's exactly how it should be. Stuck in trauma, bound by trauma; fate without intervention is solace, but not the cure. And not a happy ending.

More important to most sci-fi folks, however, is the premise itself, which hangs on an overloaded balance of metaphor and contrivance:

"Spin" was a dumb but inevitable name for what had been done to the Earth. That is, it was bad physics--nothing was actually spinning any harder or faster than it used to--but it was an apt metaphor. In reality the Earth was more static than it had ever been. But did it feel like it was spinning out of control?

No. It feels like characters are stuck within their own suffocating modes of suppressed terror.

In every important sense, yes. You had to cling to something or slide into oblivion. (164)

Methinks the title has been subject to spin, just to support a weak metaphor. A more effective title would toy more with the sense of entrapment and orbital fate, which is what the narrative naturally highlights.

Contrary to the above quote, the surrounding universe is actually, in a relative sense, spinning out of control. The universe outside the membrane is aging normally, while the Earth within the membrane is exponentially slowed. One billion years pass in the universe during a quarantined Earth decade. Yet, Wilson's references to surrounding celestial bodies, other than the sun, remain stagnant in their relative locations to the Earth. Within the time frame of the book, shouldn't we expect other planetary orbits to change, perhaps erratically? Might Mars, which factors into the plot, be closer or farther from Earth? Might planets crash? Isn't the Oort Cloud, which also factors into the plot, moving inward, increasing the risk of planetary collisions with comets? And isn't the Milky Way absorbing Andromeda by this time?

All questions that Wilson begs you not to ask. Like Christopher Priest'sInverted World (1974), the mind-bendy setting serves as schema for more important things, rationale need not apply. But where Priest's manipulated world hosts the context for probing at the whole of humanity (and genre constructs), Wilson's fishbowl world hones in solely on his three main characters, which, when applied to concerns about overbearing fathers, the attraction of religious fervor, and arrested emotional development, speaks to greater humanity, though not in any grand philosophical way. (And Inverted World's ultimate rationale for the setting is perfectly satisfactory given the context, whereas this, not so much.)

In the context of history, however, Spin might provide future generations with greater insight into the post-911 social psychology of the United States, with its amorphous enemy, unpredictable threat levels, and a pervading sense of disillusionment, disempowerment, and paranoia. (Had Wilson's prose mirrored and reinforced that sense of suppressed dread, the tale would be much richer, but Wilson isn't that kind of writer.) Like many works of this period, it appears that Wilson, whether consciously or subconsciously, is reacting to current events, and Spin is a very American novel, its insulated self-absorption present at all times. There are times when Wilson's setting seems to forget the other side of the world exists, often to the detriment of technical synthesis (and the bigger picture).

Spin's popularity spun a trilogy (and now a TV series, I just discovered), so perhaps the scientific holes are filled elsewhere. Metaphorically, this can be a satisfying read, the character stories are compelling (though more so in the first half), and the premise is pretty cool. Readers who can overlook technical holes, utilitarian prose, and the unfit title will find this novel to be a better-than-average average novel, with sophisticated character insight.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com