![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

12/18/2015

![]()

To borrow Robert Silverberg's erroneous phrasing about James Tiptree's gender, there is something "ineluctably" American about British author John Brunner's style (or variety of styles, rather). Last week, I said as much about Charles Stross's format when compared to his British author peers, but with Brunner, this isn't about American formula, it's about feel--a consciously American feel-- which heightens his work, impressing itself into the pages with brash entitlement, bold statements, and clean prose. This consistency in feel is all the more striking considering the range of styles his novels explore.

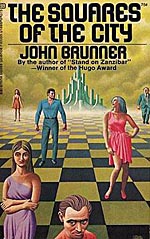

It's all the more noticeable in The Squares of the City, his 1965 Hugo-nominated novel about an Australian traffic planner commissioned by the city of Vados, capital city of the fictional South American nation of Aguazul, to do the near-impossible: make the perfect city of Vados more perfect by solving its minor traffic problems. But controversy surrounds the project when the traffic troubles take on a human aspect, and what at first appears to be an innocuous Latin American city transformed by wealth, reveals a more sinister agenda of politics and game-playing.

Ignoring the fact that traffic analyzer Hakluyt is supposed to be Australian (the voice in my head insists he's American), the bold, yet noncommittal protagonist is the embodiment of first-world, middle-class indifference with an exotic tourist visa, i.e. the ugly American. He's judgmental, wary, naïve, and ignorant--aware of his limitations, yet not aware enough to manage his deepening involvement with the amoral Vados city officials. When it becomes apparent that "the traffic problem" is actually a culture clash between the wealthy Vados citizens and displaced country peasants, Hakluyt realizes he's been brought in as a pawn, recruited to eradicate the peasant ghettos and spark a housing crisis that city officials hope will drive away the destitute while leaving them free of the blame.

A more accurate and nuanced depiction of Latin American culture than White SF typically offers, where even Vonnegut's incisive humor fails to look under all of the rocks, Squares recognizes the roots of colonialism in modern Latin American society: class resentment, racism, disenfranchisement, and greed. Brunner assembles the most insidious aspects of these symptoms into a loose political thriller of amoral game-playing. In the real Latin America, few tourists recognize those dirty street beggars in the city centers of beach getaways as disenfranchised survivors of imperial-oppression-followed-by-corporate-welfare; fewer realize those beggars don't even speak Spanish, much less identify with the ruling government. Brunner is aware of this and, while the size and scope of Brunner's novel is too small to adequately capture the marginalized victims of Vados society, he at least subverts the stereotypes and expectations that first-world readers might have unknowingly internalized by portraying a heterogeneous society of conflicting interests. By not acknowledging mainstream expectations of a spicy Latin tale with seduction, betrayal, and drugs, Brunner paints a society of complex people, rather than a picaresque shoot 'em up.

A more accurate and nuanced depiction of Latin American culture than White SF typically offers, where even Vonnegut's incisive humor fails to look under all of the rocks, Squares recognizes the roots of colonialism in modern Latin American society: class resentment, racism, disenfranchisement, and greed. Brunner assembles the most insidious aspects of these symptoms into a loose political thriller of amoral game-playing. In the real Latin America, few tourists recognize those dirty street beggars in the city centers of beach getaways as disenfranchised survivors of imperial-oppression-followed-by-corporate-welfare; fewer realize those beggars don't even speak Spanish, much less identify with the ruling government. Brunner is aware of this and, while the size and scope of Brunner's novel is too small to adequately capture the marginalized victims of Vados society, he at least subverts the stereotypes and expectations that first-world readers might have unknowingly internalized by portraying a heterogeneous society of conflicting interests. By not acknowledging mainstream expectations of a spicy Latin tale with seduction, betrayal, and drugs, Brunner paints a society of complex people, rather than a picaresque shoot 'em up.

It has its limits, however. To be more nuanced would require a bigger book, an unwieldy story, and quite frankly, would demand more insight than the white, British Brunner can provide. Brunner knows his weaknesses, so his outsider, first-world protagonist is the ideal vehicle for an introductory display of the causes and consequences of Latin American inequality. Something deeper would have to come from an insider--characters who receive slightly more than superficial treatment from Brunner's point-of-view. In addition to the limitations of scope and culture, Brunner employs an inflexible structure, modeled after a famous 19th century chess game (Steinitz v. Chigorin, 1892), to instigate moves and kill off characters. This structure confines the development of his tale to just one path, which isn't particularly beholden to much empathic grandstanding or making room for the sympathetic and disadvantaged people in his tale.

This can all be forgiven within the context of that structure, however, because it all fits metaphorically: The angular plot movements, the engagement of upper echelons of society, even the blocky text- the chess metaphor is a prime form for communicating an outsider's observations of a silenced, oppressed minority and a manipulative, inhumane upper class. This is Brunner's conscientious approach to Latin American society. His agenda is clear and considerate, an interesting outcome considering the neglectful tone of the novel.

The most noticeable blunder, however--aside from the lack of any speaking characters from the margins of Vados society-- is the lack of U.S. meddling in Vados affairs. An oil-rich South American nation is not impossible to imagine. An oil-rich South American nation that thrives on its own profits while seeming entirely self-enterprising and insulated from international intrusions and U.S. passive-aggressions is more difficult to believe than space opera FTL or fantastic quests to throw away jewelry.

Of course, there is no chess piece called "CIA agent" or "exploratory profiteer", so acknowledgement of foreign interests wouldn't fit Brunner's structure. It's also possible that the hegemonic machinations of everybody's favorite sugar-and-oil-playground bully wasn't a well-known interpretation of events in the mid-60's, when Red Fear clouded American understanding of US-Cuban relations, and years before the CIA-encouraged Chilean coup d'etat of 1973. Even today, little of mainstream English-speaking media covers Latin American news, despite it being a trove of natural resources lured by American interests daily. (When President Obama declared Venezuela a "national security threat" last spring, it barely made a ripple in the U.S. news cycle. Spanish-language news swarmed with it.) Still, Brunner should know better, and the lack of international presence inSquares undermines his focus on the inequalities inherent in Latin American culture by placing it in a vacuum, missing an ideal opportunity to reinforce his agenda of highlighting the consequences of colonial legacy by mirroring it with neocolonial, capitalist hegemony.

Social commentary aside, most readers take issue with Brunner's strict adherence to the chess-like structure of his character game-playing. Because of this construction, to call it a political thriller is an overstatement--no character arc is sympathetic enough to foster suspense, the political machinations are overextended to fit the framework, and the "elimination" of characters is sudden and arbitrary. But that's a surface complaint. Like a game between masters, the plot moves are cool and decisive, distant and devised. While Squares will engage intellectually, it won't drive page-turning with a series of shocks. This isn't such a bad thing. For readers suspicious of the manipulated suspense that comes with most political thrillers, Brunner's aloof focus and bold strategy might be just right.

Social commentary aside, most readers take issue with Brunner's strict adherence to the chess-like structure of his character game-playing. Because of this construction, to call it a political thriller is an overstatement--no character arc is sympathetic enough to foster suspense, the political machinations are overextended to fit the framework, and the "elimination" of characters is sudden and arbitrary. But that's a surface complaint. Like a game between masters, the plot moves are cool and decisive, distant and devised. While Squares will engage intellectually, it won't drive page-turning with a series of shocks. This isn't such a bad thing. For readers suspicious of the manipulated suspense that comes with most political thrillers, Brunner's aloof focus and bold strategy might be just right.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com