![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

8/11/2016

![]()

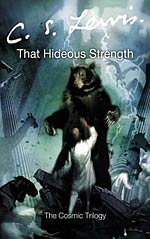

That Hideous Strength (1945), on the other hand, is far more engaging, as well as something quite different from the previous two books. The finale to a theological space trilogy that has nothing to do with space; Lewis instead combines the propriety of English fantasy with the sorcery of Arthurian romance, with almost inverted depictions of love and loyalty and obedience. Like the previous two novels, its philosophy is traditional and stifling, anti-science and sexist, but it's done in a more relevant and provocative way. It is the kind of book I can enjoy disputing.

Jane is experiencing strange, precognitive dreams while her husband, Mark, a university fellow, is being vetted by a vague but promising research position at the secretive new scientific institute (NICE) that just came to town. The institute is changing the dynamics of their quiet university town, perhaps more deliberately than it appears, and Mark's involvement requires him to cross moral lines in order to gain the trust of the inner circle and solidify his new position. But when NICE starts to show an inordinate amount of interest in Jane, Mark starts to question the virtues of this agency while Jane starts to question the virtues of their marriage.

Without a doubt, Jane is the most fascinating character in this novel, a modern women with modern, feminist sensibilities who pursues a Ph.D., foregoes having children, and despises retail therapy.

She was at least very vividly aware how much a woman gives up in getting married. Mark seemed to her insufficiently aware of this. Though she did not formulate it, this fear of being invaded and entangled was the deepest ground of her determination not to have a child -- or not for a long time yet. One had one's own life to live. (71)

Her thread in the story, which oscillates between reality and precognitive dreams ("just the news" as she starts to call them), illustrates a very real yet dreamlike sense of suffocation and aimlessness: unhappy in her marriage, an ill-fit for society, and without a purpose. Mark's increasing involvement at NICE furthers her sense of alienation and confusion.

By this point in the trilogy, however, Lewis' personal views have been explicated enough to rouse distrust in this depiction. What feels like a perfectly natural and common depiction of a female character in 2016 is actually just sarcastic derision by C.S. Lewis circa 1945.

Or is it? Because Mark thinks some shitty things that seem out of place even for 1940's literature:

Mark had shuddered at the clumsy efforts of the emancipated female to indulge in this kind of humor, but his shudders had always been consoled by a sense of superiority... (p. 66)

A misogynistic statement to say the least, but is followed just a few lines down by:

Mark was gradually horrified by her assumption that about thirty per cent of our murder trials ended by the hanging of an innocent man. There were details, too, about the execution shed which had not occurred to him before. (p. 66)

Which, given Lewis' tendency toward a humanistic form of Christian apologetics, also feels like sarcasm aimed at this type of patronizing male character. In addition, this dichotomy tends to fall in favor of Jane more often than not, which becomes clearer toward the end of the novel when even dimwitted Mark starts to recognize her as the hero of what was supposed to be his story.

Still, this is no feminist treatise; the point of this exercise is to depict the fallibility of man AND woman, and to depict the infallibility of God, which becomes all the more apparent during an argument Jane has with the angelic Ransom, the leader and "Fisher King" of Jane's crew, over the necessity of Mark's permission for her to join the group. Ransom tells her, "No one has every told you that obedience -- humility -- is an erotic necessity," (145), which seems strong coming from his surrogate god position until Mother Dimble dismisses Jane's concerns about his old-fashionedness, sort of:

My dear, the Director is a very wise man. But he is a man, after all, and an unmarried man at that. Some of what he says, or what the Masters say, about marriage does seem to me to be a lot of fuss about something so simple and natural that it oughtn't to need saying at all. But I suppose there are young women nowadays who need to be told it. (165)

The point being, even Ransom is flawed. (And might be C. S. Lewis himself, who tries, but really doesn't know what to make of women within his worldview, and might be slightly aware of this problem.) Fortunately, Jane still isn't quite convinced by Mother Dimble's tepid reassurance when she says:

You haven't got much use for young women who do, I see. (165)

There are other interesting and relatable elements: post-war discussions about communism, urban decay, police brutality, ambition and meritocracy, and irresponsible media, but although the main purpose of the novel (and the entire trilogy) is to pit Science against Religion, the burden of marriage, the burden of patriarchal oppression, as well as the more humorous burden of Arthurian fantasy on a marriage are themes that form a complete arc throughout the entire novel. In so many ways, this novel is really like any postmodern depiction of marriage: the dissatisfaction followed by disintegration followed by uncomfortable open-endedness... although we know, in the end, that in C. S. Lewis' worldview, all things through God are good.

She wanted to be with Nice people, away from Nasty people--that nursery distinction seeming at the moment more important than any later categories of Good and Bad or Friend and Enemy. (134)

And that quote there seems to be the crux and crest of Lewisian thought, making me wonder what arguments he would pursue had he been confronted with Kohlberg's famous Stages of Moral Development (or even Gilligan's later feminist rendering) recognized that his own attempts at "universal" moral code never surpass the middling, conventional levels of Good, Bad, Nasty, and Nice.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com