![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

6/15/2016

![]()

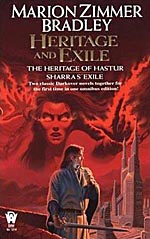

"In 1975," Marion Zimmer Bradley recalls in the middle preface of herHeritage and Exile omnibus edition, "I made a landmark decision; that in writing The Heritage of Hastur, I would not be locked into the basically immature concepts set forth in Sword, even at the sacrifice of consistency in the series" (401). This is promising, though not promising much, given the puerile nature of the 1962 Hugo-nominated science-fantasy novel The Sword of Aldones, which reads like a preteen's self-insert fanfic that unself-consciously acts out sentimental scenes with her crush. (Here is my own version of this torture. Enjoy.)

Less immature, perhaps, but Heritage of Hastur feels like the staid and stagnant fantasy fiction of Bradley's Golden Age influences -- the Kuttner and Moore type of pulp where the most dynamic things going on are the exclamation marks -- even though Bradley is writing several decades later, amid the New Wave revolution, no less. After six moreDarkover novels, and a number of other writings, Bradley still can't give hero Lew Alton a personality, but she at least makes the circumstances of his peers a little bit more interesting.

Heritage gives fans a glimpse of the pre-adult lives of two majorDarkover characters: Regis Hastur, future monarch, and Lew Alton, a bastard noble. Roles reversed in their early lives: Regis, given third-person treatment, serves as a cadet in the King's Guard, while Lew, the narrator of his own thread, serves as officer. Regis also lacks the prized, inherited "laran," a kind of intense and dangerous semi-telepathy, while Lew has mastered the skill. Also depicted is Danilo, Regis' cadet partner and roommate, victim of the unwanted advances of the older and sadistic Cadet Master, Dyan Ardais. (yep, she went there.)

"A telepath's love life is always infernally complicated." (231)

Most notable about this otherwise plodding, overreaching tale is its treatment of homosexuality, mostly expressed in its metaphor of telepathy, (much like Sword, where telepathy was a metaphor for hetero sex). As it turns out, Regis, the unlucky in telepathy heir, is a latent telepath, his laran blocked only by his repressed homosexuality. His sexual and empathic constipation is further complicated by his tense friendship with Danilo, who keeps Regis at arms-length and is eventually removed from his post after his accusations against the predator Dyan. On Darkover, homosexuality is more tolerated than accepted, so most of the narrative is only suggestive of the tensions between Regis and Danilo, though they fall into one another's arms at the end. The message being: know yourself, be true to yourself, or you will never have true "rapport" with others. If left alone -- regardless of the crappy writing and boring plot -- the Regis and Danilo arc marks Heritage as a seminal work in LGBTQ SF.

"A lustful thought is the psychological equivalent of a rape." (308)

But there is the curious case of the sadistic pederast Dyan which bungles things up. In 2016, it's difficult to not see Dyan Ardais as a stand-in for MZB's husband, the public now cognizant of the history of child sex abuse and neglect within the Zimmer-Bradley/Breen household, with this book written in the middle of their marriage, years after Walter Breen's very public convictions and ongoing accusations within the fandom. Dyan is, at first, characterized as a predator who then traumatizes the sensitive Danilo with his advances, but is later humanized through an open, and somewhat sexually tense, conversation with the more hearty Regis. Although Regis testifies on Danilo's behalf against Dyan later, the core argument of the narrative justifies sex with minors, or in very least shrugs it off,as long as it is welcomed.

This dismissal aligns with Bradley's own testimony about her husband's behavior toward children, as well as the dark and twisted rabbit hole that is 1960s California fandom gossip (which too often also wrestles with the "it's gross, but is it really hurting the children?" question in such a way as to pretty much solidify my never going to a con ever ever ever fucking ever that shit was too recent to risk being stuck on an elevator with those people). (That I have to state it again, just in case folks don't get it: Even ignoring the most basic of human cognitive and sexual development models, the rule is: there is no consent when people with power, rights, majority status have sex with people without power, rights, and majority status. It is abuse. This applies to any sexual relations with the office assistant, the student, the client, the immigrant houseworker, and, not least of all, children.)

Dyan's characterization is a strange case: condemning in some scenes, apologizing in others. The apologism might have seemed minor and nuanced -- and perhaps went unnoticed -- in the sixties and seventies, especially when measured against the grander themes of the story, but those scenes speak loudly when considered within the context of the now public lifestyle of MZB and her husband, especially given the 2014 testimony of her (traumatized to the point of irrational homophobia) daughter. To even forgive those slights in favor ofHeritage's progressive treatment of homosexuality seems backwards considering MZB chooses to follow the old-fashioned and inaccurate tendency to associate homosexuality with pedophilia. Add to that the poor, stilted writing (only slightly improved from the childish Sword of Aldones) and duller-than-dull contrived plot about dangerous matrix power, and this story is hardly worth regard.

Nebula nominated.

*And by the way! Lifted from Wikipedia: "In 1962, the noted criticDamon Knight stated that "(h)er work is distinctively feminine in tone, but lacks the clichés, overemphasis and other kittenish tricks which often make female fiction unreadable by males".[34]" There is nothing distinctively feminine about Darkover. And kittenish tricks! My book review index of too many male writers indicates that male writers have cornered the market on cliché and overemphasis. (Has Damon Knight ever written a review that wasn't completely idiotic? Here's another example where he misses the mark.)

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com