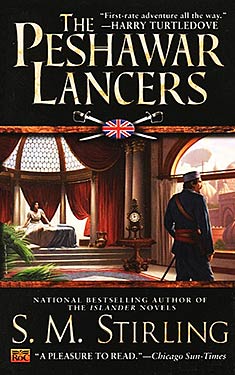

The Peshawar Lancers

| Author: | S. M. Stirling |

| Publisher: |

Roc, 2002 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Alternate History (SF) Steampunk |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In the mid-1870s, a violent spray of comets hits Earth, decimating cities, erasing shorelines, and changing the world's climate forever. And just as Earth's temperature dropped, so was civilization frozen in time. Instead of advancing technologically, humanity had to piece itself back together....

In the twenty-first century, boats still run on steam, messages arrive by telegraph, and the British Empire, with its capital now in Delhi, controls much of the world. The other major world leader is the Czar of All the Russias. Everyone predicts an eventual, deadly showdown. But no one can predict the role that one man, Captain Athelstane King, reluctant spy and hero, will play....

Excerpt

Chapter 1

Captain Athelstane King rinsed out his mouth with a swig from the goatskin water bag slung at his saddlebow. Even in October this shadeless, low-lying part of the Northwest Frontier Province was hot; and the dust was everywhere, enough to grit audibly between his back teeth. When he spat, the saliva was as khaki-colored as his uniform or the cloth of his turban. It made a brief dark mark on the white crushed stone of the military highway that snaked down from the Khyber Pass to Peshawar.

Looks the way I feel, he thought. Dirty, tired, pounded flat. Necessary work--nobody who'd seen a village overrun by hill-tribe raiders could doubt that--but not much glory in it.

Right now the Grand Trunk Road was thronged with the returning men and beasts of the Charasia Field Force, following the path trodden by generations of fighting men--for most of them, by their own fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers. Feet and hooves and steel-shod wheels made a grumbling thunder under the pillar of dust that marked their passage; camels gave their burbling cries; occasionally an elephant pulling a heavy artillery piece squealed as it scented water ahead with its trunk lifted out of the murk.

Horse-drawn cannon went past with a dull gunmetal gleam, rocket launchers like bundles of iron tubes on wheels, and machine guns on the backs of pack mules. There were even a few self-propelled armored cars. Two of them were not self-propelled any longer, and were being pulled back to the workshops by elephants. King's smile held a trace of malice. The newfangled Stirling-cycle gas engines were marvelous for airships, or the motorcars that were rich men's toys on good roads. In the field, the day of the horse-soldiers wasn't over quite yet.

Staff officers with red collar tabs galloped about, keeping order in the endless steel-tipped snake that wound down from the bitter sunbaked ridges of the Border. The right margin of the road was reserved for mounted troops, and there the Peshawar Lancers moved up in a jingle of harness and flutter of pennants and rumbling, crunching clatter of iron-shod hooves on gravel. They trotted past the endless columns of marching infantry and the wheatfield ripple of the Metford rifles sloped over their shoulders.

King ran a critical eye over them as they passed; the jawans had shaped up well in the hills... for infantry, of course. There were Sikhs with steel chakrams slung on their turbans, Baluchis with long, oiled black hair spilling from under theirs, and Gurkhas in forest green with their kukris bouncing at their rumps and little pillbox hats at a jaunty angle above their flat, brown Mongol faces. There was a regiment of the Darjeeling Rifles--young men of the sahib-log doing the compulsory service required of all the martial castes--and even a slouch-hatted battalion of Australians.

King frowned slightly at the sight. They were devils in action, but an even worse headache to the high command back in camp. And their ideas of discipline were as eccentric as their dialect of English, which they had the damned cheek to claim was the pure tongue of the Old Empire.

One of their officers answered Colonel Claiborne by saying he didn't understand Hindi! Damned cheek indeed.

His own men were in good spirits as they rode homeward; they were a mixed lot--half Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus of the Jat-cultivator caste, the rest Marathas and Rajputs for the most part. Swarthy, bearded faces grinned beneath the dust and sweat, swapping bloodthirsty boasts and foul jokes, or just glad to be alive and whole. Each carried a ten-foot lance with the butt socketed in the ring on his right stirrup iron; their cotton drill kurta-tunics and loose pjamy-trousers were stained with hard service, but the carbine before each man's right knee was clean and the curved tulwars at their belts oiled and sharp. Pennants snapped jauntily beneath the steel points that rose and fell in bristling waves above.

They'd had a few sharp skirmishes, and the usual jezailachi-sniper-behind-every-rock harassment you could expect on the frontier, but the plunder had been good, and they were returning victorious.

"Quite a sight," King murmured to the soldier riding at his side. "Fifteen thousand, horse and foot and guns--enough to give even the Masuds and Afridis a taste for peace, not to mention the Emir in Kabul. Or so they all assured us, at least, when they signed the treaty."

With a bayonet at their backs and a boot up the bum, he added to himself.

The man beside him spat into the roadside dust in turn; he was a little younger than his officer's twenty-five years, broad-shouldered, with a full black beard and sweeping buffalo-horn mustachios, and snapping dark eyes above a curved beak of nose. King had spoken in English, and Narayan Singh understood it perfectly--had he not followed the young sahib from infancy as playmate, sparring partner, soldier-servant, shield-on-shoulder, and right-hand man? Had not his father been the like to the sahib's father before him? But when he replied, it was in Army Hindi, as was fitting.

"The cobra spits, huzoor, and the Pathan speaks--who will grow rich on the difference?" he grunted. "The tribes will stay quiet until they forget men dead and captives led away and villages burning. Then some fakir of their faith will send them mad with lies about their stupid Allah, and they will remember the fat cattle and silver and women of the lowlands. On that day we shall see the hillman lashkars come yelling down the Khyber once more."

King grinned and slung the water bottle back; Narayan Singh was undoubtedly right. The lashkars--tribal war bands--would come again; raid, banditry and blood feud were the Afghan idea of being sociable, having fun with your neighbors and kin, like a polo match or tea party among the sahib-log. A razziah into the Imperial territories was more dangerous than stealing from each other, but also much more profitable.

"It could be worse; we could be in the Khyber Rifles. Comfort yourself with that, bhai," he said. "We won't be stationed in some Border fort, sleeping with our rifles chained to our wrists."

Which was the only way you could be sure, when a hillman came ghosting over the wall looking for a weapon better than the flintlock jezails their own craftsmen could make. A Pathan of the free highlander tribes could steal a man's shadow, or rustle a horse from a locked room.

Another rider came trotting down the line toward him, also in the uniform of an officer in the Lancers, but with gray streaks in his brown beard and the jeweled clasp of a colonel at the front of his turban. The regimental rissaldar-major followed him, with a file of troopers behind.

King saluted, trying not to wince at the pull of the healing wound in his right arm. "Sir!" he said crisply.

Colonel Claiborne returned the gesture and frowned, an expression that made the old dusty white tulwar scar on his cheek draw up one corner of his mouth. "Dammit, you insolent young pup, I said you weren't fit for duty yet!"

"Sir, the doctor said--"

"Dammit, I'll have you know that I know a damned sight more about wounds than some yoni-doctor from the Territorial Reserve, and I say you're unfit for duty."

King forced himself not to smile; the regiment's current medico was from the reserve and was a gynecologist in civilian life. "I just wanted to see my squadron settled in before I took leave, sir."

Claiborne let approval show through his official anger. That was the answer that a good officer would give. "I assure you," he said dryly, "that the Peshawar Lancers--yea, verily even the second squadron of the Peshawar Lancers--will survive without your services until you return from convalescent leave. Dammit, you are dismissed, Captain."

Then the colonel smiled. "I'd hate to have to explain to your lady mother why you'd lost your sword arm, lad. Go on, and go soak away some of the frontier at the Club. You'll be spending the Diwali festival at home, or I'll know the reason why, dammit if I don't."

King saluted again. "Since you put it as a direct order, sir."

Then he touched the rein to the neck of his charger and fell out of the column. The rissaldar--senior native officer--of the second squadron barked an order; the unit reined in, wheeled right, and rode three paces onto the verge before drawing to a halt like a single great multiheaded beast. Only the tips of the lances moved, quivering and swaying slightly, catching the sun in a glittering ripple as a horse shifted its weight or tossed its head.

The maneuver went with a precision that was smooth rather than stiff, the subtle trademark of men whose trade was war. King rose in the stirrups to address his command:

"Shabash, sowar! Sat-sree akal!" he said, dropping effortlessly into Army Hindi, one of his birth-tongues, Imperial English being another, of course. Honor to you, riders! Well struck! "Go to your homes and women, and we shall meet again when the swords are unsheathed; the colonel-sahib has ordered me on leave."

The rissaldar raised his sword hand: "A cheer for Captain King ba-hadurl A cheer for the Afghan kush!"

King grinned as he waved his hand and cantered off. It was capital, to be called champion and killer-of-Afghans. A hand smoothed dust-stained mustachios. Even if it was deserved...

@@@

The cave where Yasmini slept was cold; she was curled into a ball under the piled sheepskins, but it was not the damp chill of this crevice in the Hindu Kush that made her shiver. It was the words and sights that ran through her sleeping brain. She knew them all too well, these visions; they were nothing like true dreams.

Instead, they were simply true, though they might be of places and deeds far away, of things that might have been, of things that might yet come to be.

This time it was of the past--some sense she could not have named told her it was the single past that could lead to this cave in this night...

A cold wind from the west flogged snow through the streets of London, piling it in man-high drifts against the sooty brick at street corners and filling the cuts made by a thousand shovels near as fast as they could be cleared. Great kettles of soup steamed over coal fires in sheltered spots, and children too young to do other work shuttled back and forth with pannikins of the hot broth. Under the wailing of the fanged wind they could hear the dull crump... crump where parties from the Royal Engineers tried desperately to blast a way for supply ships through the thickening ice on the Thames. The men and women who toiled to keep the streets cleared were bundled in multiple sets of clothes, greatcoats, mufflers, and improvised garments made from blankets, curtains, and any other cloth that came to hand. More pulled beside skeletal horses to drag sleds of fuel and food, or boxed cargo down to the docks.

When the horses died, they went butchered into the stewpots; hideous rumors spread about human bodies disappearing from the piles where they were stacked...

The immaterial viewpoint that was her suspended consciousness swooped like a bird through the wall of a building guarded by soldiers in fur caps and greatcoats, a building where messengers came and went incessantly. In a chamber within she saw a man with long dark curls and a tuft of chin-beard dyed to a black the deep lines of age on his face belied, dressed in a sober elegance of velvet and broadcloth cut in an antique style. He turned from the window, shivering despite his thick overcoat and the blazing fire in the grate.

The face was one Yasmini recognized, long and full-lipped, with a beak of a nose and great dark eyes; a Jewish face, clever and quick and intensely human. And she could feel the being of him, not just the appearance...

Benjamin Disraeli rubbed his hands together, putting on an appearance of briskness. Even Number 10 Downing Street was cold this October of 1878; sometimes the prime minister wondered if warmth was anything more than a fading dream, if blue sky and green leaves would ever come again.

"I fear must beg your pardon, gentlemen," he said to the half dozen men who awaited him around the table of the White Room.

She understood the speech somehow, even though it was the pure English of six generations past, not the hybrid tongue of the second century after the Fall. It was as if her mind rode with his, a deep well full of memory and thought, where concepts and ideas rose with a darting quickness, like trout in a mountain stream,

A wave of his hand indicated the meager tray of tea and scones. "You will appreciate, however..."

He had never taken more than a dilettante's interest in the sciences, but it was clear that an awesome amount of talent was involved in this delegation. Stokes, the secretary of the Royal Society; Sir William Thomson down from Glasgow, despite the state the railways were in; Tait likewise from Edinburgh; Maxwell from Cambridge--

It was the Glaswegian who spoke: "We would no ha' troubled ye, my lord, but for the implications of our calculations concerning the impacts the globe has suffered. Even now, we're no sure if 'twere a single body that broke up as it struck the atmosphere or a spray, perhaps of comets... consultations took so long because travel is so slow, and telegraphs no better."

In his youth, Disraeli had been something of a dandy. There was a hint of that in the way he smoothed his lapels now. "I am sure your speculations are very interesting, gentlemen--"

Inwardly, he fumed. The world has suffered the greatest disaster since Noah's Flood; God alone knows how we will survive until the spring; and yet every Tom, and Dick and Harry sees fit to demand some of my time--when that commodity is as scarce as coal.

Perhaps those who crowded into every church and chapel and synagogue in London--probably in the whole world, with mosques and temples thrown in--were wiser. They were helping keep each other warm, and at least weren't distracting him.

The annoyance was a welcome relief from the images that kept creeping back into the corners of his mind, images born of the papers that crossed his desk. Fire rising in pillars from where the hammer of the skies had fallen all across Europe, so high that the tops flattened against the upper edge of the atmosphere itself. Walls of water striking the Atlantic coast of Ireland and scouring far inland, wreckage all along the western shores of England, where the other island didn't shelter it; far worse in most of maritime Europe. Reports of unbelievably worse damage on the American side of the Atlantic. Chaos and panic spreading like a malignant tide from the Channel deep into Russia as the governments shattered under the strain.

Only the supernal cold had kept plague at bay, when the corpses of the unburied dead lay by the millions across the ruined lands.

"Perhaps we could discuss the scientific implications of the Fall at some time when events are less pressing--when the weather has improved, for example."

The professor exchanged a glance with his colleagues, then cleared his throat and spoke with desperate earnestness: "But my lord, that is precisely what we must tell you. The water vapor and dust in the upper atmosphere--there will be no improvement in the weather. Not for at least one year. Possibly..." Thomson's face sagged. "Possibly as many as three or four. Snow and cold will continue all through what should be the summer."

Disraeli stared at the scientist for a long moment. Then he slumped forward, and the world turned gray at the edges. Vaguely he could feel hands helping him into his seat, and the sharp peat-flavored taste of whiskey from the scientist's silver flask.

Moments ago he had been consumed with worry about the hundreds of thousands of refugees pouring in from the flooded, ruined coasts of Wales, Devon, and Cornwall. With finding ships to bring in Australian corn. Now...

He came back to himself--somewhat. A man did not rise from humble beginnings to steer the British Empire without learning self-mastery. Doubly so, if he were a Jew. He hadn't asked for this burden. All that I desired was to dish that psalm-singing hypocrite Gladstone, he thought wryly. Now Gladstone was dead in the sodden, frozen ruins of Liverpool, and the burden is mine, nonetheless.

"Correct me if I'm wrong, gentlemen, but as far as I can see you have just passed sentence of death on ninety-nine in every hundred of the human race. If any survive, it will be as starving cannibals."

One of the scientists dropped his gray-bearded face into his hands. "It is not we who have passed judgment. God has condemned the human race. My God, my God, why have you forsaken us?"

"Nay, it's no quite so bad as that, sir," Thomson said quickly. His voice was steady, although the burr of his native dialect had grown stronger. "Forebye the weather will turn strange over all the world; yet still the effects will be strongest in the northern latitudes, and even there worst around the North Atlantic Basin--the Gulf Stream may be gone the while, d'ye ken... In Australia they might hardly notice it, save that the next few years will be a trifle more cool and damp."

"But what of England, Sir William? What of her millions?"

The scientists looked at him. With a chill twist deep in his stomach, he realized that they were waiting for him to speak...

Yasmini screamed and thrashed against the blankets. A hard hand cuffed her across the ear, and she shuddered awake. A flickering torch cast shadows across the rough stone of the cavern wall above her, and glittered in the eyes of the man who held it. Count Ignatieff was dressed in the rough sheepskin jacket, baggy pants, and high boots of an ordinary Cossack; but nobody who saw those eyes could ever mistake him for an ordinary man. It was more than the cold boyar arrogance, or even the fact that one eye was blue and the other brown. She suspected that he thought of himself as a tiger, but it was a cobra's gaze that looked down at her.

"Veno vat, Excellency," she said. "It was a dream--"

"A true dream, bitch?"

"Yes, Excellency. But not a vision of any use; pajalsta, Excellency. One from the past. It is the vision of Disraeli, once again. Only Disraeli, Excellency."

He struck her again, but for all the stinging pain in her cheek it was merely perfunctory, if you knew the huge strength that lurked behind the nobleman's sword-callused palm as she did.

"For that you should not disturb my sleep," Ignatieff said.

His left hand toyed with an earring in the shape of a peacock's tail; it was the sigil of initiation in the cult of Malik Nous--or Tchernobog as some called Him, the demiurge worshiped throughout the dominions of the Czar in Samarkand as the true Lord of This World.

"We must be in Kashmir within two weeks. Dream us a way past the Imperial patrols." Ignatieff kicked her in the stomach. "Why do you keep seeing that damned old Jew, anyway?" he demanded.

"I do not know, Excellency--it is my very great fault, Excellency," she gasped, trying to draw the thin cold air of the heights back into her lungs. "I most humbly apologize."

But Yasmini did know, although there was nothing of conscious control in her dreams. It was the eyes that drew her--those great brown eyes, eyes that held all the pain of a broken world.

@@@

Peaceful, Athelstane King thought, as he and his orderly rode eastward at a steady mile-eating canter-and-walk pace; Narayan Singh had two spare horses behind him on a leading rein. With those, and swinging northeast around the military convoys that filled the Grand Trunk Road just now, they made good speed.

Peaceful compared to the tribal country, at least, if not by the standards of home.

Near Peshawar, the dry rocky hills of the Khyber gave way to an alluvial plain, intensely green and laced with irrigation canals full of olive-colored, silt-heavy water from the Kabul River. Plane trees lined the road, arching over the murmuring channels on either side to give a grateful shade; the lowlands were still warm as October faded. This close to a major city and frontier base the roads were excellent, even on the country lanes away from the main highway, and it was a pleasant enough ride on a warm fall afternoon.

Tile-roofed, fortified manor houses of plastered stone stood white amid the blossoms and lawns of their gardens, each with a watchtower at a corner and a hamlet of earth-colored, flat-roofed cottager-tenant houses not too far distant; this area had been gazetted for settlement more than a century ago, right after the Second Mutiny. An occasional substantial yeoman-tenant farm or small factory with its brick chimney kept the scene from monotony. Around the habitations lay the fields that fed them and the city beyond; poplin green of sugarcane, grass green of maize, jade-hued pasture, the yellow of reaped wheat stubble, late-season orchards of apricot and pomegranate, shaggy and tattered at the same time. Cut alfalfa hay scented the air with an overwhelming sweetness, and the neat brown furrows of plowed fields promised new growth next year.

People were about; mostly ryots, peasant cottagers, the men in dirty white cotton pants and tunics, women in much the same but with longer tunic-skirts and head scarves instead of turbans, both with spades and hoes, bills and pitchforks over their shoulders. There were also oxcarts heaped with melons or fruit or baled fodder, moving slowly to a dying-pig squeal of axles; a shepherd with his crook and dogs and road-obstructing smelly flock making the horses toss their heads and shy; a brace of horse-copers from the Black Mountain with a string of remounts for sale.

King took a close look at faces and gear as they went by, giving him the salaam and smiling, looking rather like hairy vultures with teeth. Hassanazais or Akazais, he decided.

Those were Pathan-Afghan frontier tribes in the debatable lands; beyond the settled, administered zone, but not beyond the Imperial frontier... not quite. In theory both were at peace, autonomous but tributary to the Sirkar, the government of the Raj. No doubt the horse-copers had kitubs--official papers--with the appropriate stamps, seals, good-conduct badges, and letters of recommendation from the Political Officers attached to their clans, all as right and tight as be-damned.

King and Narayan Singh both kept wary eyes moving until the pair jogged out of sight and for a half hour afterward, lest the officially approved traders unofficially decide on impulse to shoot the Sirkar's men in the back and lift their horses and weapons. To enliven the tedium of spying for the Emir, or half the bandit chiefs on the Border, or both and several others besides; and a modern magazine rifle was worth more than any dozen horses, to the wild tribes.

A few minutes later, a stout gray-bearded zamindar trotted by on a dappled hunter. A pair of sandy-haired Kalasha mercenaries from up in the hills above Chitral were riding at the landowner's tail with carbines in the crook of their arms, which was wise; he wore pistol and saber himself, which was also prudent. You didn't go unguarded or unarmed this close to the Border, with loose-wallahs and cattle-lifters and jangli-admis about. Nor were the local Pathans much tamer than their wild kin, even if they'd learned better than to show it over the last century.

"Good evening, Captain!" the squire called in a cheery voice, lifting his riding crop to his turban in salute. "Capital work you lads have been doing, eh, what?"

Athelstane answered in kind; in fact the Army slang for punitive expeditions of the type he'd just finished was butcher and bolt, and de-pressingly accurate.

Not quite "what the newspaper correspondents dwell an, though, he thought.

His smile was broader for the next passerby, a woman in a pony-trap with a tasseled sunshade. She was likely a wealthy man's wife, from the opulence of rings on fingers and toes and the emerald stud through one nostril, and the jeweled collar and leash on the pet monkey that climbed and chattered beside her. Her sari was of black silk shot through with silver, a fold of it over her yellow hair and the other folds showing full curves.

"Ma'rm," he said as they passed, bowing his neck and touching one finger to his brow in polite salute.

Sighing, he ignored the pouting invitation of a full lower lip and the flirting blue-eyed glance sent the tall Lancer officer's way from behind her ostrich-feather fan.

Last thing you need now is a bloody duel with a husband, he told himself sternly- And nothing could be private; there was a maid in the cart with her, and half a dozen armed retainers following behind. Dogras, he thought, looking at their blue turbans and green-dyed beards. They bristled with spears and matchlocks and knives, one resplendent in back-and-breast armor and lobster-tail helmet.

Think about the first whiskey-peg at the club instead. Think about Hasamurtis delectable rump.

"Now I know thou'rt wounded in truth, huzoor," Narayan Singh said dryly from his side, as they trotted on toward the outskirts of Peshawar town.

King cocked an eye at his companion: Huzoor meant sir, but there were ways and ways of saying it.

"What precisely did that mean, Daffadar Singh?" he asked.

Narayan Singh snorted. A daffadar was a noncommissioned man, but there was no excess of deference in his voice.

"When a pretty woman passes by smiling and making eyes, sahib, and we ride on, I know you are wounded indeed. Wounded and near death!"

Countryside gave way to villa-fringed outskirts and the broad straight streets of the Civil Lines--the military cantonment was on the south side of town. The streets were filled with wagons and light horse carts, pedicabs, cyclists--Peshawar had almost as many bicycle manufacturies as Ludhiana--and an occasional silent motorcar. The country scents of growth and manure and water gave way to a smell of humanity and coal smoke from the factories spreading south and east. Their horses breasted through the crowds of Peshawar Old Town itself, the narrow twisted streets near the Kissa Khwani Bazaar, the Street of the Storytellers, with the old Sikh-built fort of Bala Hissar frowning down from its hill.

The lanes were overhung by balconies shielded with carved wooden purdah screens, and below, the buildings were full of little chaikanas where patrons sat on cushions drinking tea laced with cardamom and lemon and smoking their hookahs. The streets were loud with banyan merchants selling dried fruit, rugs, carpets, hairy potsheen coats made from whole sheepskins, karakul lambskin caps, and Chitrali cloaks from little open-front shops; full of the smell of packed humanity, sharp pungent spices, sweat-soaked wool, horses. And of veiled women, an icily superior ICS bureaucrat waving a fly-whisk in a rickshaw drawn by a near-naked coolie, a midshipman in a blue jacket visiting his family on leave, bicyclists frantically ringing their handlebar bells, sellers of iced sherbets crying their wares...

"Good to be back to civilization," King said with a sigh.

"Han, sahib," Narayan Singh said, as they drew rein before the wrought-iron gate of the Peshawar Club. "Good to sleep where we need not keep one eye open for knives in the dark!"

King laughed and nodded, as grooms ran to take their horses.

Copyright © 2002 by S. M. Stirling

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details