Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

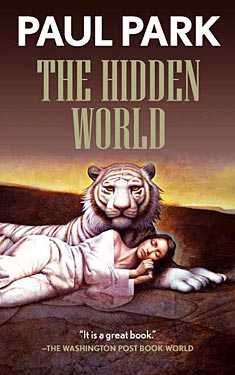

The Hidden World

| Author: | Paul Park |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2008 |

| Series: | A Princess of Roumania: Book 4 |

|

1. A Princess of Roumania |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

After finding that she is the lost princess of Roumania and the mythical White Tyger, Miranda's fate is still uncertain. The ghosts of her enemies cluster about her, the insane spirit of the Baroness takes possession of her body for a time, and demons released by her mother are abroad. Through it all her heart calls out to Peter, whom she has come to love, and to her best friend Andromeda. Any answers may lie only in the hidden world of spirits, where death is but an inconvenience, and Miranda is the most powerful creature of all: the White Tyger.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

Two hundred kilometers to the north and east of Bucharest, in a farmhouse in the village of Stanesti-Jui, Miranda lay asleep. After dinner she had retired to her bedroom with a head cold. Now past midnight, propped up on the pillows, she lay with her mouth open. Then she turned onto her side and her dream changed.

It wasn't entirely a dream. That winter in her room she had become accustomed to the many intermediate states between sleeping and waking. She had been sick for much of the season, a lung infection that, without antibiotics, had lingered until the weather turned. Her hostess, the Condesa de Rougemont, and then later her mother, had dosed her with medicinals. She'd scarcely left her room. Of course she had undertaken several small journeys to the secret world, with the help of her secret tourmaline, Johannes Kepler's eye.

Now it was almost springtime, and she was feeling better. This particular journey had started with a daydream. She had sat with a French novel, her mind wandering. And as often happened, it had wandered back to the invented refuge that her aunt Aegypta Schenck von Schenck had made for her in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, where she had gone to high school. She had lived with Stanley and Rachel, her adoptive parents, in the house on the college green in the middle of town.

Her best friend had been Andromeda Bailey, boyish and beautiful, her gray eyes spotted with blue and black and silver. Peter Gross had been in her class at school, and she had gotten to know him, too. They had spent some time together in the woods the summer Andromeda had gone to Europe. Often, as he sat cross-legged in the dirt or on a rock, he'd have a piece of a leaf or a twig in his brown hair. Often he'd have a blade of grass between his teeth. Sometimes he'd be playing his harmonica, a poor, private kind of music that she indulged. He only had the one hand. His right hand was missing because of a birth defect.

In those days all her knowledge of Roumania had come from dreams, fantasies, and a few stray memories. The facts she'd learned in school or on her own had been all lies or else distortions. The Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu, the history of Eastern Europe—no, it had been the Baroness Nicola Ceausescu who had sent an emissary to bring her home to Bucharest. His name was Kevin Markasev, and he was famous here. He'd gone all that way to find her, and he had burned the book of her invented childhood in a fire on Christmas Hill above the art museum. Then morning came and the world was different. Peter and Andromeda were different, too.

Daydreaming in Stanesti-Jui, Miranda had found her way to Christmas Hill again, and she had climbed it in the dark. She had climbed back to the start of the story. The French novel lay in her lap, spine up, inverted. Three-quarters of the way through, already she could see the end, the denouement. It was reassuring and annoying to perceive it in the distance, the place where everything was sealed up in a circle and some kind of homecoming was possible, some journey or at least some reference to the beginning once again.

You'd go back, and you'd know something new. And you would take consolation from that new thing, a consolation that was phony and real at the same time.

So she indulged herself. She closed her eyes and imagined the dark night, the bonfire in the hummocks of grass on the hillside. The place was still there for her, and in a moment she could see it clearly, and Kevin Markasev above her with the little book, her essential history, the entire story of her childhood, balanced in his hands. Only this time as he dropped it, she thought she might reach up to catch it, bat it away from the consuming fire. Andromeda was there, and Peter might come running down to help her, tripping and sliding down the slope. As she struggled with Kevin Markasev, he might pull him off her, chase him away. And she'd lie on her back. Maybe she'd have knocked her head against a stone. And Peter would be on his knees above her. "Are you all right?" he'd say, reaching to touch her face. "Are you all right?" he'd repeat, and she'd be happy to hear his voice, even though he might be implying some kind of weakness.

Of course I'm all right, she'd think, and then she'd say aloud, "I'm fine," which maybe she could make into the truth.

But the question was, if she had known then what she knew now, would she have wanted to preserve the book or to destroy it? Would she have been strong enough to hold out her bruised hands, accept the changing world and everything that was to come? In the dream she was not strong enough. Propped on pillows in her bed in Madame de Rougemont's farmhouse, she found herself muttering these words again: "I'm fine." Her French novel dropped to the floor.

She turned onto her side. Her daydream was no longer in her strict control. It had turned into an actual dream, a provisional dream only one step below consciousness. The three friends left Kevin Markasev where he lay stunned beside the burning fire. They left him and continued down the cow field, through the fences and the trees, until they reached the art museum parking lot at the bottom of the hill. There was some tension between them as they split up, each to walk home through the deserted predawn streets.

And when she reached her parents' house, the door was unlocked. She slipped inside as silently as she knew how. She could see from the front hall where Rachel had fallen asleep on the couch. She had waited up, which was comforting and irritating. She lay under the tartan blanket, curled up, mouth out of shape on the pillow. Sleep had cleaned her face; Miranda wouldn't wake her. Silent as a ghost, she climbed the stairs to her own room on the third floor, feeling wired and exhausted from the eventful night. In the bathroom on the landing she undressed, put on her PJs, flossed and brushed her teeth. Then she slipped into her cozy bed, cozy and private as this one in the farmhouse, on the slope of the mountain outside of town.

She fell asleep, and in her dream her aunt Aegypta came to her.

This was a different kind of dreaming, deeper and more powerful. It felt like being awake. Aegypta Schenck was dressed in a long coat trimmed with fox fur, and the little wicked heads hung down. She was wearing gloves, and a small pillbox hat was pinned to her gray hair. Her face was partly covered in a veil. "Ma petite chère," she said.

Miranda wouldn't let her start with that. She sat up in her bed, which in her dream was the one she actually occupied, in Stanesti-Jui. "Tell me," she said in English. "I was thinking about Peter Gross. Peter and Andromeda, my friends. Tell me, where are they?"

There was a pause. Miranda could see part of her aunt's face under the veil. Her lips were thin.

"Pieter de Graz is in Staro Selo with the Eleventh Mountaineers. There is a Turkish offensive in that area."

Miranda knew that much herself. She could see her aunt's lips, part of her nose. Her smile had no joy in it: "My dear girl. You will not fail to surprise me, the loyalty you give to these two men, your father's aides-de-camp. They were junior officers, and the ones closest to hand in a time of crisis. That is all. They were meant to protect you, at which task they have not distinguished themselves. Instead, you have saved de Graz's life more than once."

As sometimes happens in dreams, Miranda tried to speak but couldn't. "I am punished for my cowardice and my mistakes," continued her aunt. "I have been dead six years, and I am punished every day. In the book I gave you to take to Massachusetts, I described a war in Europe, a terrible war—do you remember? You asked me about it once."

Now she pulled her veil back, and Miranda could see her eyes. They had a yellow tinge. She went on: "It was my plan to give you a book in a language you didn't know, and as a grown woman you would learn to read it. Later you would follow the directives I had printed out, and with the coins I left in your possession you would find your way to Great Roumania. By yourself, you would find your way. I thought perhaps I would not live to see it—not that it mattered. But you would be wise with the wisdom from the book and your own life."

Fat chance, Miranda thought, and tried to speak. But she could not speak aloud.

"Then my enemies were planning my destruction," her aunt said, "and I didn't want to die. I thought of a new plan, and I goaded Nicola Ceausescu to send that boy to bring you home—prematurely, as it turned out. And now the coins were for me, so you could free me from tara mortilor. Blind Rodica and Gregor Splaa, who were my contingency, now supported the entire scheme, and they were too weak for that. And you were too young to be sensible when I met you in the land of the dead. There also you worried about de Graz and Prochenko, because of the damage they had suffered. It was not meant to be like this. Mixtures of people and animals from two worlds—what good are they now? As for me, I gambled my life and could not win it back. And I think this is the reason: I could not bear the thought of never seeing you again."

Because this was a dream, it could not capture the emotions of the real world. Her aunt Aegypta's voice was calm, her face almost expressionless. "Oh, my dear, you were too young. And you are still too young. Too young for these tools I have put into your hands. Too young to leave your friends behind and accept your fortune. Too young to listen to my guidance."

Copyright © 2008 by Paul Park

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details