Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

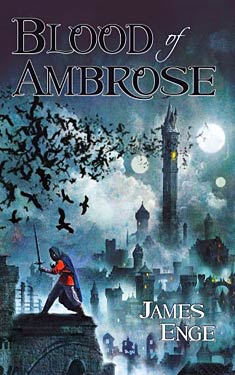

Blood of Ambrose

| Author: | James Enge |

| Publisher: |

Pyr, 2009 |

| Series: | Morlock the Maker: Book 1 |

|

1. Blood of Ambrose |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Juvenile Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Behind the king's life stands the menacing Protector, and beyond him lies the Protector's Shadow...

Centuries after the death of Uthar the Great, the throne of the Ontilian Empire lies vacant. The late emperor's brother-in-law and murderer, Lord Urdhven, appoints himself Protector to his nephew, young King Lathmar VII and sets out to kill anyone who stands between himself and mastery of the empire, including (if he can manage it) the king himself and his ancient but still formidable ancestress, Ambrosia Viviana.

When Ambrosia is accused of witchcraft and put to trial by combat, she is forced to play her trump card and call on her brother, Morlock Ambrosius—stateless person, master of all magical makers, deadly swordsman, and hopeless drunk.

As ministers of the king, they carry on the battle, magical and mundane, against the Protector and his shadowy patron. But all their struggles will be wasted unless the young king finds the strength to rule in his own right and his own name.

Excerpt

Chapter One

Summons

The King was screaming in the throne room when the Protector's Men arrived. He knew it was wrong; he knew he was being stupid. But he was frightened. When the booted feet of the soldiers sounded in the corridor outside, he belatedly came to his senses. Dropping to the floor, he crawled under the broad-seated throne where the Emperor sat in judgement, next to God Sustainer. (Only there was no Emperor now, and Lord Urdhven, the Protector, made his judgements in his own council chamber. Did the Sustainer dwell there now? Or still upon the empty throne? Was there really a Sustainer? Would the Protector's soldiers kill him, like all the others?)

He pulled in his legs just as the soldiers entered the room, their footfalls like rolling thunder in the vast vaulted chamber. He'd hoped they couldn't see him. (Would God Sustainer protect him? Was there really a Sustainer?) But the soldiers made straight for the throne.

If the Sustainer was not with him (and who could say?), the accumulated precautions of his assassination-minded ancestors were all around. As he pressed instinctively against the wall behind the throne, it gave way and he found himself tumbling down a slope in the darkness. Briefly he heard the shouting voices of the soldiers turn to screams, and then break off suddenly. Because the passageway had closed, or for another reason? His Grandmother would know; he wished she were here. But she was far away, in Sarkunden--that was why the Protector had moved now, killing the family's old servants like pigs in the courtyard....

He landed in a kind of closet. There were cloaked shapes and bits of armor lying around in the dust that was thick on the floor. Perhaps they were, or had been, things to help an endangered sovereign in flight or self-defense. He thought of that later. But just then he only wanted to get out; by flailing around in the dark he found the handle of a door and plunged out into the bright dimness of a little-used hallway.

Hadn't he been here before? Hadn't Grandmother told him to come here, or someplace like here, if something happened? He hadn't been listening. Why listen? What could happen in the palace of Ambrose, with the Lord Protector guarding the walls... ? And they had cut his tutor's throat, cut Master Jaric's throat, and hung him upside down to drain, just like a pig. He had seen it once at a fair, and Grandmother had said he must never, never do that again.

The sudden memory renewed his terror; he found himself running down the corridor in the dim light, the open doors on either side of him yawning like disinterested courtiers. There was a statue of an armed man standing over a broad curving stairway at the end of the hall. The King was almost sure Grandmother had mentioned a place like this, but without the statue. If he went down the stairs, perhaps that would be the place, and he would remember what Grandmother had told him to do next--if she had told him.

But as he passed the statue it moved; he saw it was not a statue--no statue in this ancient palace would be emblazoned with the red lion of the Lord Protector. The Protector's Man reached for him.

The King fell down and began to scuttle away on all fours, back down the corridor. The Protector's Man dropped his sword and followed, crouching down as he came and reaching out with both hands.

"Now, Your Majesty," the soldier's ingratiating voice came, resonating slightly, through the bars of his helmet. "Come along with me. No one means to harm you. Just a purge of ugly traitors who've crept into your royal service. You can't go against the Protector, can you? You found that out. And stop that damned screaming."

The King was screaming again, weary hysterical screaming that made his body clench and unclench like a fist. Looking back, he saw that the soldier had caught hold of his cloak. There was nothing he could do about the screaming, just as there was nothing he could do about the soldier.

Then Grandmother was there, standing behind the Protector's Man, fixing her long, terribly strong hands about his mailed throat. The soldier had time for one brief scream of his own before she lifted him from the floor and shook him like a rag doll. After an endless series of moments she negligently threw him down the hall and over the balustrade of the stairway. He made no sound as he fell, and the crash of his armor on the stairs below was like the applause that followed one of the Protector's speeches--necessary, curt, and convincing.

Before the echoes of the armed man's fall had passed away, Grandmother said, "Lathmar, come here."

Trembling, the King climbed to his feet and went to her. Grandmother frightened him, but in a different way than most things frightened him. She expected so much of him. He was frightened of failing her, as he routinely did.

"Lathmar," she said, resting one deadly hand on his shoulder, "you've done well. But now you must do more. Much more. Are you ready?"

"Yes." It was a lie. He always lied to her. He was afraid not to.

"I must remain here, to keep them from following you. You must go alone, down the stairway. At the bottom there is a tunnel. Take it either way to the end. It will lead to an opening somewhere in the city. Go out and find my brother. Find him and bring him here. Can you do that?"

"How... ? How... ?" The King was tongue-tied by all the impossibilities she expected him to overleap. He was barely twelve years old, and looked younger than he was, and in some ways thought still younger than he looked. He was aware, all-too-aware, of these deficiencies.

"You know his name? My brother's name?"

"His name?" the King cried in horror.

"Then you do know it. Say it aloud. Say it to many people. Say, 'He must come to help Ambrosia. His sister is in danger.' By then I will be, you know."

The King simply stared at her, aghast.

"He has a way of knowing when people say his name," the King's grandmother, the Lady Ambrosia, continued calmly. "That much of the legend is true. But more is false. Do not be afraid. Say the name aloud. You are in no danger from him; he is your kinsman. He will protect you from your enemies, as I have done."

From the far end of the corridor echoed the sound of axes on wood.

"I had hoped to go with you," his Grandmother continued evenly, "but that will not be possible now. You will have to find someone else to help you; I wish you luck. But remember: if you do not find my brother, I will surely die. Your Lord Protector, Urdhven, will see to it. You don't wish that, do you?"

"No!" the King said. And that, too, was a lie. It would be a relief to know he had failed Grandmother for the last time.

"Go, then. Save yourself, and me as well. Find--"

Knowing she was about to say the accursed name, her damned brother's name, he covered his ears and ran past her, skittering down the broad stone steps beyond. He passed the corpse of the fallen soldier. He kept on running.

By the time the light filtering from the top of the stairway failed, he could see a faint yellowish light gleaming below him. When he reached the foot of the stair, he found a lit lamp set on the lowest step.

His feelings on reaching the lamp were strong, almost stronger than he was. He knew that his Grandmother had set it here to give him not only light, but hope. It was a sign she had been here, that she had made the place safe for him, that he need not be afraid. As he lifted the lamp, he felt an uprush of strength. He almost felt he could do the task his Grandmother had set him. He swore in his heart he would succeed, that he would not fail her this time.

Choosing a direction at random, he walked along the tunnel to its end. There he found a flight of shallow stairs leading upward. He climbed them tentatively, holding the lamp high. At the top of the stairs was a small bare room with one door. The King turned the handle and looked out.

Outside was a city street. It was long after dark, and wagon traffic was thick in the streets, in preparation for the next day's market. (Cartage into the city was forbidden during the day, to prevent traffic jams.)

The King closed the door and sat down on the floor next to his guttering lamp. But presently it occurred to him that sooner or later the Protector's Men would discover the tunnel and draw the obvious conclusion. No matter how dangerous the city was at night (he had heard it was; he had never set foot in the city unattended, day or night), he knew he should leave this place.

He stood impulsively and, leaving the lamp behind him, stepped out into the street.

Night to the King meant a dark room and the slow steps of sentries in the hallway outside. Night was an empty windowcase, a breath of cold air, the three moons, wrapped in a smattering of dim stars, peering through his windows, and the sullen smoky glow of Ontil--the Imperial city--to the east. Night was quiet, and the kind of fear that comes with quiet, the fear of stealth: the poisoned cup, the strangler's rope, the assassin's knife.

This night was different: a chorus of shouting voices, the roar of wooden wheels on the cobbled street, the startled cries of cart-horses. It was like a parody of a court procession, with the peasants in their high carts moving in stately progress--when they moved at all. The King, who had never been in a traffic jam (though he had caused many), wondered why they were moving so slowly, when they were all so obviously impatient. Then he saw that they all had to negotiate a sort of obstacle at the end of the street: a row of stone slabs stretching across the way, so that each cart had to slow to fit its wheels through the gaps in the stone causeway, and all the carts behind it perforce slowed as well. When the stones were higher than a cart's axles, or when no gap in the stones corresponded to the width of a cart's wheels, the delay was longer; the cart had to be pulled over, or unloaded and lifted over, or shunted aside.

Above the chaos of lamps the stars were almost invisible, but the King could see Trumpeter, the third moon, standing bright beneath the sky's dim zenith. The major moons, Horseman and great Chariot, were down--this was the month of Remembering, the King remembered. (He didn't have to bother much with days or months; he just did as he was told when someone told him to do it.)

Fascinated, the King crept along the narrow stone walkway toward this center of activity. Before reaching it he saw that, beyond the relatively narrow street, there was a great square or intersection into which several other streets emptied out. All of the traffic converged on one very large way that seemed to lead to the great marketplace or market district. (The King was hazy about the geography of the Imperial city, one of the two that he, in law, ruled.)

It was horrible, with the noise and the dust and the reek of the horses--sweat and manure--and the shouts of the peasants and the glare of the cart lamps (dazzling in the darkness of the otherwise lampless street). Horrible but fascinating. The King believed that the noise, the dirt, the confusion would drive anyone mad. But the peasants did not seem mad, only annoyed. The King had no idea where they were coming from, and only the vaguest as to where they were going, but did not doubt there was backbreaking drudgery at either end. The King was not exactly sure what "backbreaking drudgery" entailed, but it was something (he had been told many times) that was not expected of him. This relieved him greatly, as he considered his life hard enough as it was. Surely none of these peasants had a Grandmother like the Lady Ambrosia, or an uncle like Lord Urdhven.

On the far side of the street he saw three figures, cloaked, masked, booted, gloved, all in red. They carried something between them... he saw an arm trailing on the ground and realized it was a dead body. So the red figures must be members of the Company of Mercy, the secret order that tended to the sick and buried the bodies of the city's poor--no one knew where. There were strange stories about the red Companions; no one ever saw their faces, or knew where they came from. There were bound to be stories.

One of the red-masked faces turned toward him as he stood on the sidewalk, open-mouthed, watching the traffic pass, and it occurred to him again that the Protector's Men would be coming for him soon. At the moment he was just another mousey-haired, underdeveloped, twelve-year-old boy in dark clothes wandering the city streets. But when the Protector's Men started asking questions, some of the people passing by might remember that they had seen him. He had to get on his way, and immediately.

But where should he go in the dark city before him? What was he to do? To find Grandmother's brother, of course. But he would have to ask someone. There were many people here, many of them from outside the city, some of them, perhaps, from very far away. This was the place to begin.

The King shrank from the thought of what he was about to do. But the memory of the lamp in the dark tunnel returned to him, renewing his hope and his strength. And there was a trembling exultation in the thought that if he succeeded, he would bring hope to his Grandmother as she had brought hope to him. He had never done anything like that before.

Not allowing himself to think, he leapt away from the wall and hopped from stone to stone across the intersection, as if they were the stepping-stones in his garden stream in the palace. A cart was slowly being pulled through the gap in the stones.

"The Strange Gods eat these roadblocks," the driver was cursing. "They should make them all the same size. How's a man supposed to bring his goods to market?"

"We could market at Twelve Stones," the driver's shadowy companion observed.

"They won't pay city prices, my lad. When you--Hey! What do you want?"

This last was addressed to the King, who had leapt over to cling to the side of the cart.

"Help me!" the King said.

The driver turned to look at him. He was a heavy-shouldered peasant in a dark smock. His face was sun-darkened; it had flat features and flat black eyes like stones, and a flat gray beard. "Help you what?" he asked reasonably. Beyond him the King could see his companion, a gaping young man with straw-colored hair and the barest beginnings of a beard.

"Help me find... " the King began, then stopped. Who? Grandmother's brother. But she wasn't really his grandmother--he just called her that because it was shorter than "great-great-great-great-etc. grandmother." And what did you call the brother of your great-great-who-knows-how-many-greats grandmother? He didn't think there was a word for that.

"My... she... I'm... my... my... my--"

"Get your story straight," advised the driver as the cart surged forward into the open; with dispassionate skill, he lifted his whip and cut the King across the face.

Too shocked even to scream, the King felt, as from a great distance, his nerveless fingers let the cart go; he fell to the filthy cobbles of the open square. Dazedly he watched the lamplit cart roll away in the dark toward the other lights clustering at the thoroughfare entrance.

Slowly the King rose to his feet. The whipcut was a red lightning-stroke of pain across his face, and other dark fires were burning on the side of his head, his right side and limbs where he had fallen. He did not fully understand why the driver had done what he did. But he guessed that the same thing would happen unless he did as the driver had advised, and got his story straight.

He would not tell them about his Grandmother. (That would only frighten them away, because she was the Protector's enemy, and the Protector ruled everything now.) He would not tell them anything--except what she had told him to say. Say the name aloud...

He climbed back up on the stepping-stones and bided his time. Presently a cart came through and, while it was fully engaged in passing through the line of the stepping-stones, he jumped into the tarp-covered back of the wagon, landing on his feet, and prepared to dodge whip-strokes.

"Hey, thief!" shouted the driver, a heavyset elderly man raising his whip (as the King had feared).

"No, Rusk!" the passenger, a woman of the same age, cried. "It's a little boy!"

The King did not think of himself as "a little boy." He had seen little boys from far off, playing in the streets below the walls of the palace Ambrose, and he was not much like them. He usually thought of himself as "a child," since that was how others referred to him when they thought he was not listening, often quoting the ancient Vraidish proverb "the land runs red when a child is king."

"They're the worst thieves of all!" Rusk grumbled, but lowered the whip. "Hey, boy! You're spoiling our vegetables!"

"I'm sorry," the King said. "I need help." He shifted to the side of the cart, to avoid treading on their goods. The cart jerked as it pulled free of the stepping-stones, and the King almost fell into the square again. "I need to find somebody!" he cried, clutching at the wagon's side.

"Who?" the woman asked.

The King paused. Now that he came to it, it was difficult to speak that awful name aloud. "The Crooked Man," he said then; it was one of many euphemisms for Ambrosia's brother.

Rusk, looking forward now to guide the cart-horses, gnashed his teeth in irritation. "Boy, you should know that beggars don't come out at night. Besides, we're not city people; we don't know any beggars, crooked or straight."

"I don't understand what you mean," the King said slowly. "I mean... I am looking for... Ambrosia's brother. The Dark Man."

The woman gave a sharp intake of breath, and Rusk shouted, "Lata, this is on your head. Throw that rat off our wagon before he says the name and brings a curse on us--"

"Morlock!" shouted the King in despair, as the woman reached back in a vague swatting motion. "Morlock! Morlock! Morlock! Your sister is in danger! Morlock!"

He had expected (well, half expected) the Crooked Man to appear in a gush of flame, as legends said he did when his name was spoken, to work dreadful wonders, or haul traitors off to hell. So he was half disappointed when nothing of the sort occurred. A cart with a lamp (Rusk and Lata's had none) passed them; a wash of golden light passed over the old woman's seamed face, catching a speculative wondering look on 'her features as she met the King's eye.

Rusk had reined in and was turning around, shouting, whip in hand. As he raised his arm to strike, Lata snatched the whip away from him and said in a breathless voice, "Shut up, Rusk, you fool--and you, too, sir, if you please," she added, glancing back at the King. "Sit down there, out of the passing lights, sir, and you'll be quite comfortable."

"Sir!" exploded Rusk.

"Don't you understand?" Lata said insistently. "It's the little king!"

Rusk drew himself up, then glanced back at the King, who had settled himself down obediently into the shadows. "It's impossible," Rusk said, but his voice was quiet and lacked all conviction.

Lata, her voice equally quiet, drove the point home. "Who counts the coins on market-day, Rusk? I do. If I've seen his face once I've seen it a hundred times. And you remember what the gate guard said, about the disturbance at Ambrose. If the Protector and old Ambrosia are finally having it out, she might call on her brother (the Strange Gods save us from him; I name him not). What'd be more natural?"

"'Natural'!' Those ones... " Rusk's voice was sardonic, but held no disbelief. Hope beat suddenly in the King's heart.

"Then you'll help me?" the King said. "You'll help me find Morlock?"

"Shut that filthy-mouthed brat up."

"Shut up yourself, Rusk. It's different for him; the Crooked Man (I name him not!) is his kin, in a manner of speaking. Yes, little sir, we'll help you as best we can. Bless you, it's our duty now, isn't it? Just pull some of these blankets over you and lie down on the side of the cart, there. There now. There now. That's fine."

Lata and Rusk did a good deal of low-voiced talking, but the King didn't bother to listen to it. He had done his part; he had succeeded; it was up to the others, now. He hoped they would be in time to save Grandmother--how proud she'd be of him, for once! He wondered at the power of the Crooked Man's name, which frightened others even more than it did him. Lata had said, it's different for him, and he saw how true that was.

"Morlock," the King muttered, and felt the ancient blood of Ambrosius glow in his veins. "Come help us, Morlock. Help Grandmother. Hurt the Protector. He killed my parents, Morlock, I'm almost sure of it.... " The King whispered to Morlock in the dark what he had never dared to say aloud to anyone, even Grandmother. But he didn't have to be afraid anymore; it was a wonderful feeling.

He peered through the boards of the wagon side. Would Morlock appear magically out of the darkness, as he was supposed to do when someone said his name? Would he be hunched over and crooked, as the legends said? Would his fiery servants appear alongside him? Was his hand really bloodred, from all the killing it had done? But Morlock never appeared.

That was all right, though. The King knew it was because they were going to meet him. Lata and Rusk seemed to know more or less where to go. Rusk was expressing delight at how empty the streets were; the King guessed that people avoided the streets, because that was where Morlock lived.

After a while the King grew tired of muttering Morlock's name in the dark. He risked peering out of the wagon past Lata and Rusk. He saw the high twisting towers of a palace, the windows glittering with light. He wondered dimly if Morlock had his own palace, his own court, a kind of secret Emperor.... But that was impossible. He knew those towers. He had seen them, looking up from the palace walls, as he walked with the sentries.... It was Ambrose. They were taking him back to Ambrose.

"You're taking me back!" he shouted, throwing off the blankets. "You lied! You said you'd help!"

Rusk said nothing, flicking the reins to make his horses go faster. But Lata turned toward him, her etched face expressionless in the shadows, her voice troubled and concerned. "Now, now, young sir. We are helping. It's best you not be mixed up in that nasty old witch's plots. And you can't be wandering the streets at night, no, no. Why, who knows what might happen? You'll be safer at home in... in the palace, there. Let the grownups settle things between themselves. Now, don't be afraid. Don't cry. No matter what happens, they won't hurt a boy like you."

The King was crying, in fear and frustration. If the Protector had murdered the Empress, his own sister, why would he stop at killing anybody? They had killed Master Jaric and drained him like a pig, and who did Jaric ever hurt? The King wanted to call out Morlock's name again--Morlock who was death to traitors--but the power to do so had left him.

He wondered, briefly, fearfully, what would happen if he jumped away from the wagon and ran away into the dark streets. He didn't know. He didn't know. He didn't do anything. There was no point in doing anything. He had done something and it hadn't worked. The King sat, weeping as the wagon pulled up in front of Ambrose's City Gate. He did not even listen as Rusk and Lata began their marketplace chaffering with the guards on duty.

"Wait, wait, wait!" the guard captain said finally. "You two--go over there and claim that person these two are talking about. You see him there, in the back?" The King heard booted feet approaching, and felt himself lifted gently out of the wagon by his shoulders, then carried bodily to the gate. He opened his eyes to meet those of the guard captain, who swore furiously, "Death and Justice! It's true. Thurn and Veck: take His Majesty back to his apartments and stay with him. Don't be drawn off by anyone or I'll feed the one ball you have between you to the goats. Carnon: notify the Protector's Man napping upstairs in the inner guardhouse that we have recovered the King. I know; I know! Then you go with him while he reports to the Protector, and just you mention it to everyone you meet. Nobody's falling down a stairway on my damn watch."

"Wait, now!" Rusk said hoarsely. "Little sir, won't you speak up for us? This soldier man is trying to cheat us of our reward! Didn't we help you get home safe, all right? Won't you mention us to your Protector?" And through this the King saw Lata tugging at Rusk's arm, begging him to be quiet and come away. Then the soldiers carried the King through the gate, onto the open bridge over the river Tilion, towards the yawning gate of Ambrose on the far side of the river, and the darkness, and the fear.

The guard captain's voice, now lazily threatening, echoed back through the City Gate. "Hold on. This isn't some sack of beans you've brought to market. It's the royal person, His Majesty Lathmar the Seventh, the King of the Two Cities and (the Strange Gods willing) your future Emperor. As to the Protector hearing your names, there's little doubt of that. Now--what are your names? Where do you live? How did you become involved in the abduction of His Majesty? Which one of you slashed his face?" The gate of Ambrose shut behind the King.

Grandmother was condemned to death the next evening, along with all the people the Protector's Men had killed the night before, in a special session of the Protector's Council. The King never remembered much about the ceremony, just that Grandmother (in the plain brown robe of the accused, her empty hands hanging loose from the wrist as if they had been broken) looked at his face once and turned away.

They had given him a statement to read before the Council, but he burst into tears and couldn't say anything. They took him away and put him to bed. After a while he stopped crying or moving so that they would think he was asleep and go away. When they did, he lay there in the dark room, thinking.

The last thing he thought, many hours later, when he really was falling asleep, was that the things they said about the Crooked Man were all lies. He would never believe a legend again, or his Grandmother either.

As for Lata and Rusk, they had been released that morning, after a bitter night of questioning. It soon proved that no one really believed they were involved in a plot to abduct the King. The guard captain, Lorn--not a Protector's Man, one of the City Legion--who assumed charge of their interrogation was simply furious at them. He referred several times to their attempt to "sell the King like a sack of beans." But he kept the Protector's Men away, and finally dismissed them when it was too late to make it to the Great Market (which ceased to admit vendors at dawn), contemptuously declining to confiscate their goods. As they drove their wagon away from Ambrose, Lata felt obscurely ashamed, yet intensely angry--as if she had tried to cheat someone, only to find herself cheated instead.

Rusk's feelings were less ambiguous, and he gave vent to them all the way back to their farm. He cursed everyone they had dealt with, from the Protector on down, not excluding the King ("that foul-mouthed fucking little brat") or Ambrosia ("the evil venom-spewing bitch"). Frequently he exclaimed, "Morlock take them all!" because he considered himself to have been ill used, if not positively betrayed.

They sold most of their goods at Twelve Stones, for a fraction of what they would have gotten at the Great Market. Their ride home was another long litany of curses, this time including the day's buyers and competing sellers, but concentrating as before on the Protector, the guard captain, the ungrateful King, and that inhuman crook-back witch Ambrosia. Rusk invited Morlock to show himself and cart off each one in several directions.

Lata, whose shame had grown as her anger faded, finally told him to shut up. But the grievance became something of an obsession with Rusk, and for years afterward he was liable to mutter, "Morlock take them! Morlock take them all!" particularly when he was doing some dirty or disagreeable task.

The pattern for all this was set on that first day, when they returned home to find the young nephew they had hired to watch their farm missing, their scarecrow stolen, and a murder of crows feeding in their wheat field. Before anything else, Rusk had to rush hither and thither through the field, waving his arms like a madman to scare away the crows. This he did while screaming out such treasonable abuse of the imperial family that even the crows were shocked. The repeated references to Morlock caught their attention, too, for they had a treaty with Morlock. It was the treaty, rather than Rusk's ineffectual gesticulations, that caused the murder to rise up into the air, showering Rusk with seeds and croaks of abuse, and fly off into a neighboring wood for a parliament.

They settled between them how much they actually knew of the story--this took some time, since crows are quarrelsome and apt to suppose they know more than they do--and they agreed on who was to carry the message. They then determined Morlock's location by the secret means prescribed by the treaty and dispatched the messenger. Their duty discharged, the parliament adjourned and the murder flew back to pillage Rusk's wheat field again.

But the messenger-crow flew east and north till night fell and day followed night. He flew on, pausing only to steal a few bites of food now and then, and catch an hour's sleep in an abandoned nest. At last, after sunset on the second day, the messenger flew over a hillside where a dwarf and a man with crooked shoulders were sitting over the embers of a campfire; the man was juggling live coals with his bare fingers. The messenger-crow settled down on his left shoulder and spoke into his ear.

Copyright © 2009 by James Enge

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details