Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

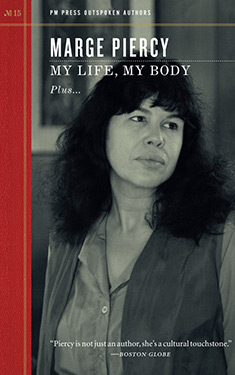

My Life, My Body

| Author: | Marge Piercy |

| Publisher: |

PM Press, 2015 |

| Series: | Outspoken Authors: Book 15 |

|

1. The Left Left Behind |

|

| Book Type: | Non-Fiction |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In a candid and intimate new collection of essays, poems, memoirs, reviews, rants, and railleries, Piercy discusses her own development as a working-class feminist, the highs and lows of TV culture, the ego-dances of a writer's life, the homeless and the housewife, Allen Ginsberg and Marilyn Monroe, feminist utopias (and why she doesn't live in one), why fiction isn't physics; and of course, fame, sex, and money, not necessarily in that order. The short essays, poems, and personal memoirs intermingle like shards of glass that shine, reflect--and cut. Always personal yet always political, Piercy's work is drawn from a deep well of feminist and political activism.

Also featured is our Outspoken Interview, in which the author lays out her personal rules for living on Cape Cod, finding your poetic voice, and making friends in Cuba.

Contents:

- A Dissatisfaction without a Name

- The More We See the Less We Know

- Headline: Lawmaker destroys shopping carts

- Gentrification and Its Discontents

- What they call acts of god

- Statement on Censorship for the Pennsylvania Review

- Fame, Fortune, and Other Tawdry Illusions

- Housewives without Houses

- The hows; there is no why

- "Living off the Grid" Outspoken Interview with Marge Piercy

- Touched by Ginsberg at a (Relatively) Tender Age

- Tabula Rasa with Boobs

- Nice words for ugly acts

- Why Speculate on the Future?

- My Life, My Body

- Behind the war on women

- Never Catch a Break

- Port Huron Conference Statement

- Who has little, let them have less

- Bibliography

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

A DISSATISFACTION WITHOUT A NAME

When did I first become a feminist? I suspect it was around puberty, when I began to think hard about what I saw in my family and around me.

My mother had been sent to work as a chambermaid when she was still in the tenth grade, because her family was large and poor and needed the income she could bring in. She had an active mind, a strong sense of politics and an immense curiosity. She read a great deal, haphazardly. She had no framework of knowledge of history or economics or science in which to fit what she read or what she experienced, so that intelligent observations jostled superstitions and folk beliefs. She was a mental magpie, gathering up and carrying off to mull over anything that attracted her attention, anything that glittered out of the ordinary boredom of being a housewife. There was, truly, something birdlike about her, a tiny woman (only four feet ten) with glossy black hair who would cock her head to the side and stare with bright dark eyes.

She had grown up in a radical Jewish family where politics was discussed and debated. She had a sense of class conflict and social reality that was the most consistent and logical part of her mind. My father could easily be seduced by racism, sexism, Republican promises of lowering taxes. Like many working class men of his time, he started out on the left and moved steadily toward the right. My mother never wavered in her analysis of who was on her side and who was not. She trusted few politicians, but she appreciated those she thought fought for the rights of ordinary people.

My father very much enjoyed sexist jokes and told them till the end of his life, ignoring my attitudes if I was present. They were a way of knocking on the wooden reality of how things were with men and women and showing how sound it was. My mother did not tell such jokes and seldom laughed at them. However, she had attitudes of her own. She admired women who fought for other women, but she also had contempt for women. She complained of women's weakness, at the same time that she herself had few strengths to fall back on. She viewed sex as a powerful force that carried off women into servitude. A woman's sexuality was a tremendous force that exacted a lifelong price from her.

When I was little, I thought of my mother as very strong -- for certainly she had power over me. My father would punish me severely, with fists and feet and a wooden yardstick. But my mother was usually the one who set the rules, since my father did not take much interest, except sometimes to decide I must do something I didn't want to do, because he had contempt for cowards: climb a ladder to the roof, cross a narrow high footbridge. These demands had little to do with me, but were part of a war between them. She had many fears (he was driving too fast, too dangerously) that in some way pleased him. Her fear proved he was strong and able, in comparison to my mother (whom he never taught to drive). But I was the battleground in which he demonstrated how women were afraid by demanding I do things I feared.

So I learned to do them. I learned to overcome my fear and do foolhardy things never without thinking but without giving an outward sign of my fear. I did it partly in a futile effort to gain his respect, which could never be granted. That respect was never attainable because of my sex and because my mother and I were Jewish, and he was not. He was not anything in particular. He thought of himself as English, Anglo- Saxon, but he was only one quarter English; he was half Welsh and one quarter Scottish. He was far more a Celt than an Anglo-Saxon. He was a moody man who feared and denied emotions; they were what he regarded as sins. He liked to drink; he liked to eat what he regarded as proper masculine food (meat and potatoes mostly); he liked to play poker and other card games. But he intensely disliked being aware that he felt anything except anger. His anger was swift and thunderous. He never hit my mother but he frightened her. Again, I was the surrogate. He could and did hit me. Also my older brother.

My mother had a temper of her own. She got angry as quickly as he did. She had a far more vivid vocabulary of curses, some in Yiddish (used only with me), most in English. "Shit and molasses!" she would yell. "Piss blood and drink it!" Her temper was released on me, of course, and on objects. I remember her at the kitchen table pulling the cloth laden with supper -- dishes and food and flowers -- and throwing it against the wall. She broke dishes with abandon. Never the good dishes. No, she broke the mismatched dishes she got as giveaways at the movies or bought at garage and yard sales.

She was not a middle-class lady. She cursed, she thought of herself as fastidious but wasn't, she lost her temper, she liked bright colors and gaudy objects. She was overtly sexual. She was immensely curious and loved plants and animals. She was always hungry for conversation, for communication, for something of interest. My early and middle childhood centered around her. My father was dangerous but peripheral. When I was young, I could not understand why she never seemed to get what she wanted.

I remember a particular birthday of hers, which came in November, the year I turned thirteen. My mother always fussed about presents. She would shop carefully for my father, sometimes buying his gift several months in advance. She liked to give presents and she desperately enjoyed being given them. I always gave her as nice presents as I could afford. That went on until she died at eighty-seven (we think). I still have many of them.

For her birthday, my father gave her a new garbage can for the kitchen and a broom. She wept for hours. There was not only boredom in the gift but insult. I brooded over this, wherein lay the insult. I said to her, why don't you buy yourself what you want? Why does he have to give it to you? Why don't you go out and buy yourself a good red dress, a new coat, a leather purse? She looked at me as if I was crazy and said, "He'd never put up with me spending that kind of money on myself."

"What business is it of his what you spend money on?"

Again she glared at me, an idiot child. "It isn't my money."

I began then to understand why my mother had to defer to my father, why my mother could yell and sulk and wheedle and brood but could never win. She worked all the time, obviously, but the only money she had was what he gave her for the house. They quarreled constantly about how much she spent on groceries. Everything was controlled by him. He bought himself a new car every two or three years, but there was no money for me to go to the dentist. My teeth rotted in my mouth and broke off. It wasn't until I was putting myself through college that I spent much of my first semester sitting in the dental school having my teeth fixed by student dentists. He owned every power tool he saw advertised. I went off to college without a winter coat. My mother developed cataracts but never saw an eye doctor. At eighty-seven, she was still cleaning the house without help.

When I was fifteen, they moved to a bigger house in Detroit, where she began to rent out rooms. Now she had money of her own, finally, which she could use as she pleased. But it was too late. She said to me, "I can't leave him now. The house is in his name. I'd starve."

When my mother was eighty-six, she demanded that we drive down to Florida because she had a present to give me too big for us to carry back on the plane. She did give me a box of silver-plate that would easily have fit in a suitcase, but what she really wanted to give me waited until my father went out. Then out of hiding places all over their tiny house she pulled out single dollar bills, one after the other. For an hour she piled up dollar bills, until she had given us $1,200, stuffed in cracks in the floor, hidden in closets, thrust into coat pockets, under dresser scarves, in the bottom of dry vases. This was her immense bequest. She had saved this gift out of grocery money, squirreling it away, because she knew she was going to die soon (she had suffered a ministroke she had told no one about and soon would have another that would kill her) and she wanted to give me an inheritance. It had taken her immense effort to save and secrete these bills.

It became clear to me sometime between the ages of thirteen and fifteen that economics was the bedrock on which any independence had to be built. If I couldn't make a living, I would be as wretched as my mother. If I depended on a man to support me, I would be enslaved. It was that simple to me.

In contrast to my mother was my Aunt Ruth, who was midway between us in age. She worked. She had only a high school diploma, which kept her from advancing in the Navy when she worked for them, kept her from advancing up any corporate ladder. But she was bright, ambitious and she made a living. She took up bowling and won trophies. She was one of the only women jocks I knew. When she married and moved into a middle class suburb, she took up golf instead and soon she was filling the house with golf trophies. She was a far more observant Jew than my mother, but she was also more worldly. She dressed like a working woman and wore slacks -- then a novelty. She had no children and she spent her money as she pleased, even after she married.

Her husband began to beat and abuse her. She had my grandmother living with her half a year and half with us. That complicated Ruth's choices. My mother said, Poor Ruth! What can she do? But Ruth cut through it all and ran off with another man who was much kinder to her and with whom she lived the rest of her life. She eloped, taking my grandmother with her. It was clear to me that if you earned your own money and you had the guts to do what you wanted, you would never be stuck -- as my mother was.

I went through childhood and adolescence brooding a great deal about the war between women and men, about the inequalities I saw and did not want in my own life. I had no word for my concerns, no political framework in which to think about what I observed. For the next ten years, whenever I was involved with a man, I would eventually feel an enormous weight of despair. Both men and women told me that was how things were, unequal, and that I should accept the female situation with graceful acquiescence because it had always been so and would always be so: this was the message of high and low culture, from the novels and poetry we read to the messages of advertisements and men's and women's glossy and pulp magazines, the movies we went to, the songs played over the radio. Everything said, men are strong and women are weak, and women like it that way. Men rule and women are ruled, and women like it that way. Men earn money and women stay home and have babies and raise babies (and then what?) and spend money. Men think; women feel. Men plan; women flirt. Men do; women are done. Anything else was unnatural, and what could be worse than an unnatural woman?

By my last two years of college, I was a better writer than the men around me in writing classes and in the school journals. I had begun to win prizes. Prizes were, after all, won under sexless pseudonyms. Yet I never received the respect men my age did. I could not understand why I should not be taken seriously. I had no more affairs than many of the men in my circles, yet my few affairs were scandalous and I was a scarlet woman, a shameless hussy.

Similarly, I had no name for the invisibility that came over me when I married, left graduate school and began to work as a secretary to support my husband's graduate studies in physics. I was aware I had suddenly become invisible, inaudible, of no account. I spent a long time figuring that one out.

Then suddenly Simone de Beauvoir put it all in focus and gave me a name for my discontent. At twenty-two, I read The Second Sex. That amazing book provided the impetus to walk out of my marriage and rethink the choices I had made. I had a vocabulary in which I could define and retain insights that had come to me for years, but which the society had labeled crazy. I was not crazy, after all. Now I knew what I was: I was a feminist.

CHAPTER 2

THE MORE WE SEE, THE LESS WE KNOW

It may be that television has addled our ability to choose a leader wisely. Between sound bites and the seduction of images we run a popularity contest every four years instead of an election.

Would Abraham Lincoln have a chance today? He was ugly. We like photogenic leaders. We want leaders who appear to be flawless in past and present, which limits the intelligence, curiosity and experience of our winning candidates. We prefer someone shallow to someone of wide and deep experience.

We have disqualified candidates for President and Vice President because they wept. Apparently an inability to feel something deeply is required for high office. Eagleton was bumped out of contention for Vice President because he had been smart enough to seek help when he needed it. Apparently we prefer untreated problems in our candidates. We respond to candidates as we have become accustomed to responding to celebrities: would we like them, do we find them attractive, can we identify with the character they project on the small or large screen?

We often appear more interested in the sexual adventures or the lack of them in our heroes than in their political positions, which would have cost Thomas Jefferson the presidency as well as Grover Cleveland, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Martin Luther King Jr. could not have led the civil rights movement if his affairs had been held against him. Sexual peccadilloes do not cost lives or wreck the economy.

Great leaders have always been flawed. Would Moses make it in sound bites? He stammered. He also was a felon and a fugitive. F.D.R. was severely handicapped. Dukakis looked like Rocky the Squirrel in a tank. We seem to believe that looking good in a military pose is far more important than having a grasp of what war actually involves to the invading country and the invaded. A sense of history would have helped immensely before we took on Iraq, but we are trained to mistrust men of ideas and obvious education. Our leaders should not appear to be smarter than we are.

The worst thing that a politician can be called is elitist -- and what do we mean by that? In Iowa, Howard Dean was labeled that -- a sushi eating, PBS watching, Volvo driving man -- not macho enough, clearly, to win the vote of working men. But who determines the massive layoffs and the movement of corporations abroad that gut the economies of so many cities and drive families from comfort into chaos? Those are the members of the real elite, and they aren't defined by eating sushi or watching PBS. There is a class of people who send their sons to the "best" private schools and the Ivy League universities, who join the interlocking boards of corporations and become their CEOs. These are the people who move the jobs to India and to China and to Guam. They are the people who support the notion that intellectuals are dangerous and intelligence is elitist. Their political propaganda claims that people who own oil companies and drive up the prices you pay at the pump are just regular guys who love NASCAR and football and eat barbeque and Big Macs. These power brokers are just luckier more and photogenic versions of you.

Often the Bible gets quoted in political contexts. But do the people who quote it actually read it? Those Bible stories resonate for us because they are often about leaders and people with important destinies -- but these men and women are not cartoon heroes. Saul would be in danger of commitment to a mental institution. David not only had an affair but got rid of the husband. Jacob deceived his father on his death bed. But they also overcame their flaws and in the long run, they carried forward a vision. It is that vision that makes them memorable and for that moral vision we still tell their stories.

Surely we could learn to vote in favor of those who will fight for our good, rather than the welfare of those who contribute heavily and profit from many governmental decisions. I wish we could learn to vote for our interests and not for the politician we think we would like best as our daddy or our pal.

Copyright © 2015 by Marge Piercy

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details