Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Engelbrecht

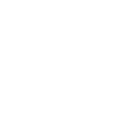

The Red Wolf Conspiracy

| Author: | Robert V. S. Redick |

| Publisher: |

Del Rey / Ballantine, 2009 Gollancz, 2008 |

| Series: | The Chathrand Voyage: Book 1 |

|

1. The Red Wolf Conspiracy |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: | |

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Six hundred years old, the Imperial Merchant Ship Chathrand is a massive floating outpost of the Empire of Arqual. And it is on its most vital mission yet: to deliver a young woman whose marriage will seal the peace between Arqual and its mortal enemy, the Mzithrin Empire. But Thasha, the young noblewoman in question, may be bringing her swords to the altar.

For the ship's true mission is not peace but war-a war that threatens to rekindle an ancient power long thought lost. As the Chathrand navigates treacherous waters, Thasha must seek unlikely allies-including a magic-cursed deckhand, a stowaway tribe of foot-high warriors, and a singularly heroic rat-and enter a treacherous web of intrigue to uncover the secret of the legendary Red Wolf.

Excerpt

Chapter One

Tarboy

1 Vaqrin (first day of summer) 941

Midnight

It began, as every disaster in his life began, with a calm. The harbor and the village slept. The wind that had roared all night lay quelled by the headland; the bosun grew too sleepy to shout. But forty feet up the ratlines, Pazel Pathkendle had never been more awake.

He was freezing, to start with--a rogue wave had struck the bow at dusk, soaking eight boys and washing the ship's dog into the hold, where it still yipped for rescue--but it wasn't the cold that worried him. It was the storm cloud. It had leaped the coastal ridge in one bound, on high winds he couldn't feel. The ship had no reason to fear it, but Pazel did. People were trying to kill him, and the only thing stopping them was the moon, that blessed bonfire moon, etching his shadow like a coal drawing on the deck of the Eniel.

One more mile, he thought. Then it can pour for all I care.

While the calm held, the Eniel ran quiet as a dream: her captain hated needless bellowing, calling it the poor pilot's surrogate for leadership, and merely gestured to the afterguard when the time came to tack for shore. Glancing up at the mainsails, his eyes fell on Pazel, and for a moment they regarded each other in silence: an old man stiff and wrinkled as a cypress; a boy in tattered shirt and breeches, nut-brown hair in his eyes, clinging barefoot to the tarred and salt-stiffened ropes. A boy suddenly aware that he had no permission to climb aloft.

Pazel made a show of checking the yardarm bolts, and the knots on the closest stays. The captain watched his antics, unmoved. Then, almost invisibly, he shook his head.

Pazel slid to the deck in an instant, furious with himself. You clod, Pathkendle! Lose Nestef's love and there's no hope for you!

Captain Nestef was the kindest of the five mariners he had served: the only one who never beat or starved him, or forced him, a boy of fifteen, to drink the black nightmare liquor grebel for the amusement of the crew. If Nestef had ordered him to dive into the sea, Pazel would have obeyed at once. He was a bonded servant and could be traded like a slave.

On the deck, the other servant boys--tarboys, they were called, for the pitch that stained their hands and feet--turned him looks of contempt. They were older and larger, with noses proudly disfigured from brawls of honor in distant ports. The eldest, Jervik, sported a hole in his right ear large enough to pass a finger through. Rumor held that a violent captain had caught him stealing a pudding, and had pinched the ear with tongs heated cherry-red in the galley stove.

The other rumor attached to Jervik was that he had stabbed a boy in the neck after losing at darts. Pazel didn't know if he believed the tale. But he knew that a gleam came to Jervik's eyes at the first sign of another's weakness, and he knew the boy carried a knife.

One of Jervik's hangers-on gestured at Pazel with his chin. "Thinks his place is on the maintop, this one," he said, grinning. "Bet you can tell him diff'rint, eh, Jervik?"

"Shut up, Nat, you ain't clever," said Jervik, his eyes locked on Pazel.

"What ho, Pazel Pathkendle, he's defendin' you," laughed another. "Ain't you goin' to thank him? You better thank him!"

Jervik turned the speaker a cold look. The laughter ceased. "I han't defended no one," said the larger boy.

"?'Course you didn't, Jervik, I just--"

"Somebody worries my mates, I defend them. Defend my good name, too. But there's no defense for a wee squealin' Ormali."

The laughter was general, now: Jervik had given permission.

Then Pazel said, "Your mates and your good name. How about your honor, Jervik, and your word?"

"Them too," snapped Jervik.

"And wet fire?"

"Eh?"

"Diving roosters? Four-legged ducks?"

Jervik stared at Pazel for a moment. Then he glided over and hit him squarely on the cheek.

"Brilliant reply, Jervik," said Pazel, standing his ground despite the fire along one side of his face.

Jervik raised a corner of his shirt. Tucked into his breeches was a skipper's knife with a fine, well-worn leather grip.

"Want another sort of reply, do you?"

His face was inches from Pazel's own. His lips were stained red by low-grade sapwort; his eyes had a yellow tinge.

"I want my knife back," said Pazel.

"Liar!" spat Jervik. "The knife's mine!"

"That knife was my father's. You're a thief, and you don't dare use it."

Jervik hit him again, harder. "Put up your fists, Muketch," he said.

Pazel did not raise his fists. Snickering, Jervik and the others went about their duties, leaving Pazel blinking with pain and rage.

By the Sailing Code that governed all ships, Captain Nestef would have no choice but to dismiss a tarboy caught fighting. Jervik could risk it: he was a citizen of Arqual, this great empire sprawling over a third of the known world, and could always sign with another ship. More to the point, he wore a brass ring engraved with his Citizenship Number as recorded in the Imperial Boys' Registry. Such rings cost a month's wages, but they were worth it. Without the ring, any boy caught wandering in a seaside town could be taken for a bond-breaker or a foreigner. Few tarboys could afford the brass ring; most carried paper certificates, and these were easily lost or stolen.

Pazel, however, was a bonded servant and a foreigner--even worse, a member of a conquered race. If his papers read Dismissed for Fighting, no other ship would have him. He would be cut adrift, waiting to be snatched up like a coin from the street, claimed as the finder's property for the rest of his days.

Jervik knew this well, and seemed determined to goad Pazel into a fight. He called the younger boy Muketch after the mud crabs of Ormael, the home Pazel had not seen in five years. Ormael was once a great fortress-city, built on high cliffs over a blue and perfect harbor. A place of music and balconies and the smell of ripened plums, whose name meant "Womb of Morning"--but that city no longer existed. And it seemed to Pazel that nearly everyone would have preferred him to vanish along with it. His very presence on an Arquali ship was a slight disgrace, like a soup stain on the captain's dress coat. After Jervik's burst of inspiration, the other boys and even some of the sailors called him Muketch. But the word also conveyed a sort of wary respect: sailors thought a charm lay on those green crabs that swarmed in the Ormael marshes, and took pains not to step on them lest bad luck follow.

Superstition had not stopped Jervik and his gang from striking or tripping Pazel behind the captain's back, however. And in the last week it had grown worse: they came at him in twos and threes, in lightless corners belowdecks, and with a viciousness he had never faced before. They may really kill me (how could you think that and keep working, eating, breathing?). They may try tonight. Jervik may drive them to it.

Pazel had won the last round: Jervik was indeed afraid to stab him in front of witnesses. But in the dark it was another matter: in the dark things were done in a frenzy, and later explained away.

Fortunately, Jervik was a fool. He had a nasty sort of cunning, but his delight in abusing others made him careless. It was surely just a matter of time before Nestef dismissed him. Until then the trick was to avoid getting cornered. That was one reason Pazel had risked climbing aloft. The other was to see the Chathrand.

For tonight he would finally see her--the Chathrand, mightiest ship in all the world, with a mainmast so huge that three sailors could scarce link arms around it, and stern lamps tall as men, and square sails larger than the Queen's Park in Etherhorde. She was being made ready for the open sea, some great trading voyage beyond the reach of Empire. Perhaps she would sail to Noonfirth, where men were black; or the Outer Isles that faced the Ruling Sea; or the Crownless Lands, wounded by war. Strangely, no one could tell him. But she was almost ready.

Pazel knew, for he had helped in his small way to ready her. Twice in as many nights they had sailed up to Chathrand's flank, here in the dark bay of Sorrophran. Both had been cloudy, moonless nights, and Pazel in any case had been kept busy in the hold until the moment of arrival. Emerging at last, he had seen only a black, bowed wall, furred with algae and snails and clams like snapped blades, and smelling of pitch and heartwood and the deep sea. Men's voices floated down from above, and following them, a great boom lowered a platform to the Eniel's deck. Onto this lift went sacks of rice and barley and hard winter wheat. Then boards, followed by crates of mandarins, barberries, figs, salt cod, salt venison, cokewood, coal; and finally bundled cabbages, potatoes, yams, coils of garlic, wheels of rock-hard cheese. Food in breathtaking quantities: food for six months without landfall. Wherever the Great Ship was bound, she clearly had no wish to depend on local hospitality.

When nothing more could be stacked, the lift would rise as if by magic. Some of the older boys grabbed at the ropes, laughing as they were whisked straight up, fifty feet, sixty, and swung over the distant rail. Returning on the emptied lift, they held bright pennies and sweetmeats, gifts from the unseen crew. Pazel cared nothing for these, but he was mad to see the deck of the Chathrand.

His life was ships, now: in the five years ...

Copyright © 2008 by Robert V. S. Redick

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details