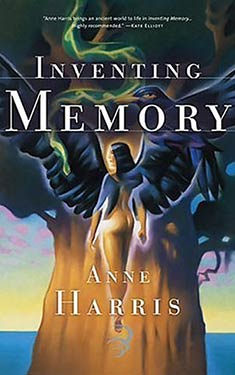

Inventing Memory

| Author: | Anne Harris |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2004 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

A one-of-a-kind novel, like nothing you've ever read, Inventing Memory is a stunning blend of fantasy and reality, exposing the secret links between the mythic, the mundane, and the timeless mysteries of the human heart.

Shula is a slave in fabled Sumer---until Inanna, Queen of Heaven, appears before her. Chosen by the Goddess for reasons she cannot begin to fathom, Shula is freed from bondage and set upon an uncertain path toward a new and mysterious destiny. But the attention of the gods is a dangerous thing, and Shula may have cause to regret the day she first laid eyes on the Holy Inanna.

Wendy Chrenko, former high school misfit, is now an overworked graduate student, researching her dissertation "Remnants of Matriarchy in the Ancient Sumerian Inanna Cycle." Still smarting from the painful wounds of a failed love affair, Wendy is bound and determined to prove that men and women once lived together in perfect equality, even if it means volunteering for a bizarre and dangerous scientific experiment.

Separated by millennia, Shula and Wendy appear to be two very different women, leading completely separate lives.

Or maybe not.

Excerpt

INVENTING MEMORY

BOOK 1

THE SERPENT THAT KNOWS NO CHARM

CHAPTER 1

Shula sat on the wall of Erech, gutting fish and watching the world be born. Beyond the city, the mudflats were hazy with dawn. Like dreams awakening, they shimmered in the fading mist and became real. Grain fields and reed beds emerged from nothingness the way the world must have, when the waters of the great flood receded.

Every morning she came here, to Inanna's gate, to clean fish and stare at the forming land. And every morning it was a different land. The flats were always changing, because the rivers that carved them like silver knives were forever flooding and changing their courses.

Erech was made out of that chaotic mud. Layer upon layer the city rose upon itself as houses were built, torn down, or washed away. Like the flats, the city was always changing, but the city had people, and no matter how many times their homes were destroyed, people would always build again, leaving their names inscribed in tablets in the walls. And so Erech grew, accreting upon itself; a tower rising in time.

Shula pushed aside the long black braid at the top of her forehead and glanced over her shoulder at the tower in the center of the city: the Temple of Inanna, which housed the goddess's holy throne. As the sun broke over its square edifice, she returned her gaze to the flats. The light stole across the rivers to hide among the reeds like a shining serpent.

In the day's first light a prayer slipped from her and flew away into the broad new sky, a wordless thing which, once flown, could not be remembered. Sighing, Shula hopped off the wall and took the basket of fish, smelling of blood and the river, to the cistern by the stairs. She ladledout water to rinse her hands and the fish, then hoisted the basket to her shoulder and went down to the street.

Farmers and shepherds flooded in through Inanna's gate, each oblivious to the others, wholly bent on the pursuit of livelihood. Oxcarts and livestock clogged the streets, and confusion reigned in the intersections, where flocks collided and intermingled. In the doorways of houses weavers wove and spinners spun. A cookshop offered up the glorious smell of frying batter to the limitless blue sky above.

Shula imagined herself up in the sky, looking down at the city. A herd of white goats came up Utu Street, a herd of black down Ninlil Street. When they met at the intersection, they got mixed up. Each shepherd came away with a speckled flock.

The ground disappeared from beneath her right foot, and for a moment Shula thought she truly was flying. Then her foot hit the bottom of the rut in the road and mud splashed up her leg. The fish jiggled and she steadied herself, looking up into the face of an oncoming donkey hauling an enormous load of hay. Shula backed out of its way and bumped into a vegetable stand. A squash, dislodged from the top of the pile, fell to the ground.

"Morning makes the day."

She turned to see an old woman winding a skein of wool in the shadowed doorway. "I'm sorry," said Shula, "the donkey ..." Balancing her basket on her hip, she bent down and retrieved the squash, replacing it on the pile.

The old woman spat on the ground between her feet. "Traffic. It's not safe to go about your business. You're likely to get trampled by some shepherd's flock. And at night! The thieves, and murderers, too. Of course they'll get you at home as well." The old woman grimaced, her eyes nearly disappearing among her wrinkles. "Sneak right into your house and strangle you in your bed just to rob you. It's appalling. In my time they would have taken them all out to the charnel houses and slit their throats. The new king is too lenient at home, always going off to war or to kill monsters. How can he rule the city if he's never here? Does he think the grain grows by itself? Does he think the sheep tend themselves? The bread his soldiers eat comes out of our mouths, they feast on our mutton and takethe hides from our beds. We used to have bountiful harvests, and the sheep fed on wild grass. It gives them a different taste. The mutton now has no flavor."

Shula's mouth watered at the mention of mutton. She'd had only a piece of bread this morning. Wild grass or no, she relished mutton when she could get it.

"Not that the congress is any better," the old woman went on. "They don't listen to us either."

Shula turned away from the woman and her dissatisfactions and braved the streets once more. If she did not get these fish back before their eyes turned cloudy, Abpahar would have her flogged. Dodging peddlers' carts and slaves hauling sledges of bricks, she wound her way to Ur-Neattu's house. She took the alley to the back gate, slipping through the outer wall and into the warm frenzy of the kitchen. The fire melted the morning from her, and for a sudden moment, she wanted to run back out, to save that chill, watery consciousness.

"Shula." Lugalla, orchestrating the clamor of cook pots, still managed to spot her. "The fish, bring them here. Did you clean them?"

Shula nodded and handed her the basket. Lugalla eyed them critically and deposited them on the counter.

"You're late," the cook said. "Abpahar awakes."

Shula ran to the cistern at the center of the court and drew a basin of water, which she carried to Abpahar's room. Abpahar reclined on her sheepskin padded platform, already throwing off the fine woolen blanket. Shula set the basin on a low platform beside her bed. As Abpahar washed, Shula combed her mistress's long black hair, plaiting it in braids close to the scalp.

"I dreamt I was making barley cakes," said Abpahar. "The grain was speckled and soft-hulled."

Shula smiled and tucked a stray hair into the plaits. "Your next child will be a daughter, and easily born."

Abpahar sighed and shooed her away from her hair. "After Ilshubur, I had hoped it would be some time before I returned to childbed. A girl you say?"

"Yes, because the grain was speckled."

Abpahar shook her head. "Another boy would be a close brother to Ilshubur, he's so much younger than Pada-Sin. A third girl will be out of place in the household."

"Marat will be happy, she tires of being the younger daughter. And you will be glad of another girl when Kalaghiri marries and goes to live in the house of her husband."

Abpahar grunted and tilted her chin. Shula leaned forward, carefully outlining her mistress's eyes with kohl. "Yes, it will be soon," murmured Abpahar. "Already she trades glances with boys in the marketplace. A mother loses her daughters to their husbands, but sons she keeps all her life. My grandmother once told me that in her mother's time women remained with their families after they married. It was the husband who took up residence in his wife's home." She stood, and Shula helped her put on her skirt and shawl. "She said some young women even served as divine prostitutes for a year, learning Inanna's sacred rites. These women were most prized as wives, but now every child must have a father, and a bride who is no longer a maiden is useless to a man." She slipped brass bracelets over her wrists as Shula fastened the silver and lapis marriage beads around her neck.

***

Later that day, Abpahar sent Shula down to the riverbank with the washing. She knelt on the bank, pounding clothes and bedding against a broad flat rock to loosen the dirt, then pushing them into the water to be sluiced clean by the current. Once washed, she laid each article out across the reeds, to dry in the sun and air, and then she sat down on the bank once more, and watched the river roll by through the drowsy afternoon.

The sun was beginning to fall out of the sky when Shula heard a commotion upstream. She followed the noise to a bend in the river where trees grew, dipping branches and roots into the curve-slow water. Someone splashed and cursed behind a bed of reeds. Shula crept closer, peeking through the tall green stalks. A young woman with fierce eyes the color of the river looked back at her. She wore a beaded crown hung with tiny brass figures; birds and fish and date trees.

A shock of recognition went through Shula. "You're her," she said. "I sit at your gate." But what was the goddess doing here, wading about inthe mud, and why had she chosen to show herself to Shula, of all people?

Inanna stood up suddenly, flinging water from her arms and wresting her hem from the mud. She was tall, with robust thighs and breasts. Her hair hung down in long dark ringlets. "Damn snake," she muttered, squelching through the mud to throw herself heavily upon the riverbank beside Shula, who could see, beyond the reeds, a large tree lodged against the riverbank. It must have washed away upstream, and floated down the river, roots, leaves and all. Inanna waved at it. "Now how am I going to get that home?"

Shula shrugged. "What kind of tree is that?" It wasn't a date palm or a fig tree. It had a different kind of leaf, like a fish's tail.

"It's a huluppu tree, the very first tree," said Inanna. "I'm going to plant it in my garden and when it grows large, and has borne many seasons of fruit, then I will have it cut down, and make my bed and throne out of it. Just think; a big bed, made of wood, and a throne."

"That's the throne that's in your temple. I saw it last year, when you got married again. Why do you get married every year?" asked Shula, biting her lips at her own temerity.

But Inanna didn't pay any attention. She poked a little trench in the mud and slid a piece of reed along it. She looked up, smiling at Shula. "The river will carry it, but you must help me."

Shula glanced downriver, where her washing lay, dry now, or as dry as the sun would get it, for day was ending. Already she would be in trouble for being late, and if the laundry were lost or stolen, she would be beaten for sure, maybe even sent out of the house to work in Ur-Neattu's fields. But she looked back at Inanna, whose eyes blazed forth as radiant as the morning sun, as terrible as a thousand armies, and she could not refuse her.

With a branch from one of the other trees, Inanna tried to pry the huluppu tree free from the bank, but it wouldn't budge. "It's stuck," said the goddess. "Go into the water and see if you can get it loose."

Shula waded into the water and tried to push the roots free. Indeed, they were mired in the thick mud of the riverbank. She bent and scooped some of the mud away from the roots, then more and more, piling it among the reeds like a miniature Erech.

Inanna gave a great push with her branch, and the huluppu tree shifted. "Help me push!" cried the goddess. "Keep it turning!"

Shula grasped the roots below the waterline and pulled. The tree rolled free of the mud with a sucking gasp, and then the current caught it, and it was moving. She turned to see Inanna smiling, but then a wrenching tug at her forehead sent her plunging into the river. It was her apputtum, her slave lock, tangled in the roots of the tree. Desperately Shula tried to tug it loose, but the water choked and blinded her. Frantically she grabbed at the roots of the tree. Her fingers brushed a slender tendril and she grasped it, winding her fingers around it and pulling herself forward. She flung her other arm up to grapple among the roots, where she found a handhold and lifted herself up, her feet scrambling for purchase on the underside of the tree. Shula heaved herself up above the water and lay gasping on the trunk of the huluppu tree.

The riverbank whizzed by. Shula craned her neck, catching a heartrending glimpse of her laundry among the reeds. She tried to pick out a few landmarks, so she could retrieve it later. If she had the laundry with her, perhaps she could invent a story for her lateness. One more believable than this.

Inanna had not jumped after her. Drowning, apparently, was for mortals. Shula watched her running along the riverbank. The goddess seemed to stand still as she paced the river's current.

Inanna pointed at something and shouted, both her and her words growing smaller as she stood still and Shula, the tree, and the river moved on. Shula turned just in time to see a sluice gate rising up, the water surging around it, white with foam. She tugged at her apputtum once more, and found it was caught around a gnarled root just before her. With desperate, trembling fingers she picked at the coiled braid, trying to loosen it, but the wet hair had tightened into a knot. With frantic strength she grasped the root and tore it free. Ahead of her, the gate was opening. It would take her into the city, and even farther from her laundry and any hope of avoiding punishment. She jumped.

The water was still cold and murky, swirling in her ears and up her nose as she bobbed to the surface. She gasped for air and got a mouthful of silty water in the bargain. Catching sight of the riverbank, she swamtoward it. The current dragged at her and panic bubbled in her throat, but she kept on until she felt solid ground beneath her feet and dragged herself, exhausted and dripping, onto dry land. She swayed on her feet, looking out at the river, but the tree had passed through the sluice gate and on into the city. Shula sat on the bank, trying to get the huluppu tree root out of her braid, and waiting for Inanna to show up. But she never did, not after Shula flung the root back into the river, not after she began to shiver in the night air.

By the time she walked back to where her washing lay waiting patiently, blessedly, on the reeds, it was full dark. Rubbing her sore scalp she gathered the laundry, hoping she didn't miss anything, and made her slow, weary way back to Ur-Neattu's house.

Lugalla was waiting for her when she got back, standing in the kitchen doorway with her wooden spoon in her hand. Shula had borne the marks of that utensil before, and she surely would again, for she'd forgotten to think up a convincing story to forestall her punishment.

Lugalla took the washing from her, set it on the counter, and then grasped Shula by the shoulders and shook her. "Where have you been? All day Marat has not had her favorite shawl, and Ilshubur is in his last swaddlings. I thought Ur-Neattu would go to bed without his rich warm blanket, and the night is cold."

Shula could confirm that. As her head bobbled to Lugalla's tempo, an attack of shivering overtook her. The walk had dried her, but when the water left her body it took with it what little heat was left. She pulled away from Lugalla, and flung herself, suddenly quaking uncontrollably, into a corner. She sank down on her haunches, curving her body and wrapping her arms over her head.

While she waited for Lugalla's spoon to strike she concentrated on trying to get warm, blowing her breath down between her legs. It helped a little. She did it some more, and gradually she stopped shaking. The spoon hadn't struck. Shula realized that Lugalla was talking to someone. She peered up from beneath her arm to see Pada-Sin, the firstborn son of Ur-Neattu, in conversation with the cook.

"But she was gone all day! With the washing!" protested Lugalla.

"Leave her to me." Pada-Sin dismissed her with a wave, and turnedhis attention to Shula, who stood up, stretching her arms shyly down the front of her river-stained skirt. Fear and hope stretched her lungs tight, and constricted her breathing.

Pada-Sin looked at her tenderly. "Shula, you are cold, your hair is matted to your head. What happened? Did you meet your lover? Did he throw you in the water? Do you have a lover, Shula?" He stood close to her, bringing her the heat from his body.

She shook her head. "No. I wasn't--I did fall in the river, but it wasn't because--There was this tree."

Pada-Sin chuckled, and placed his fingertips on her lips. "Shh. It doesn't matter. I don't care if you have a lover, Shula. I don't care." He pressed closer, and kissed her, his beard and mustaches warm and scratchy.

Yielding to his desire was a simple matter. Pada-Sin was not an ugly man, and he was clean. He had the ways of a gentle lover, even with his father's slave. With an ease born of habit, Shula closed her eyes and imagined he was a boy she once knew, the playmate of her childhood. A laughing face and arms warm as sunshine. They played among the high grasses of the steppe, and when they grew older, the tall, frond-tipped stalks hid their lovemaking. Like everything else, it was a game to them. Little did she know that he would be the one partner she chose for herself, that sex would become something others chose for her. Strange, that she could not remember his name.

When Pada-Sin left her, warmer but more tired, Shula got up and rummaged some bread and porridge from the pantry. She sat in the dark kitchen, eating and thinking about the river and what had happened there. This was Inanna's city, but the oldest person alive in it was not yet born when the goddess last walked its streets. Why had Inanna chosen to show herself now, and to her of all people? A slave girl with neither wealth nor power.

The room was lit only by the dying hearth fire, and night stole in through the door, creeping with cold dark feet to dance upon the ashes of the day.

Copyright © 2004 by Anne Harris

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details