Added By: illegible_scribble

Last Updated: valashain

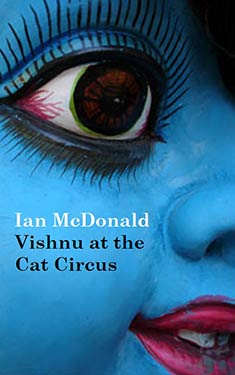

Vishnu at the Cat Circus

| Author: | Ian McDonald |

| Publisher: |

Gollancz, 2009 Pyr, 2009 |

| Series: | India 2047 |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novella |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Artificial Intelligence Nanotechnology Near-Future |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Hugo-nominated Novella

Vishnu at the Cat Circus is a novella set in the same world as Ian McDonald's 2004 novel River of Gods. It depicts a futuristic India in 2047, a century after its independence from Britain, characterized both by ancient traditions and advanced technologies such as artificial intelligences, robots and nanotechnology.

The genetically-improved Vishnu looks back on his life, in a story of a sibling rivalry with some very unexpected results.

Excerpt

They Are Saved by a Desk

Come Matsya, come Kurma. Come Narasimha and Varaha. By the smoky light of burning trash polyethylene and under the mad-eye moon lying drunk on its back, come run in the ring; ginger and black and tabby and grey, white and calico and tortie and hare-legged tailless Manx. Run Vamana, Parashurama, run Rama and Krishna.

I pray I do not offend with my circus of cats that carry the names of divine avatars. Yes, they are dirty street cats, stolen from rubbish dumps and high walls and balconies, but cats are naturally blasphemous creatures. Every lick and curl, every stretch and claw is a calculated affront to divine dignity. But do I not bear the name of a god myself, so may I not name my runners, my leapers, my stars, after myself? For I am Vishnu, the Preserver.

See! The trash-lamps are lit, the rope ring is set, and the seats laid out, such as they are, being cushions and worn mattresses taken from the boat and set down to keep your fundament from the damp sand. And the cats are running, a flowing chain of ginger and grey, the black and the white and the part-coloured: the marvellous, the magical, the Magnificent Vishnu's Celestial Cat Circus! You will be amazed, nay, astounded! So why do you not come?

Round they run and round, nose to tail. You would marvel at the perfect fluid synchronisation of my cats. Go Buddha, go Kalki! Yes, it takes a god to train a cat circus.

All evening I beat my drum and rang my bicycle bell through the heat-blasted hinterland of Chunar. The Marvellous, the Magical, the Magnificent Vishnu Cat Circus! Gather round gather round! There are few enough joys in your life: wonder and a week's conversation for a handful of rupees. Sand in the streets, sand slumped against the crumbling walls of abandoned houses, sand slumped banked up on the bare wheel rims of the abandoned cars and minibuses, sand piled against the thorny hurdles that divided the river-edge sandbars into sterile fields. The long drought and the flashfire wars had emptied this town like so many others close to the Jyotirlinga. I climbed up to the old fort, with its view twenty kilometres up- and downriver. From the overlook where the old British ambassador had built his governor's residence I could see the Jyotirlinga spear into the sky above Varanasi, higher than I could see, higher than the sky, for it ran all the way into another universe. The walls of the old house were daubed with graffiti. I rang my bell and beat my drum but there was never any hope of even ghosts here. Though I am disconnected from the deva-net, I could almost smell the devas swirling on the contradictory airs. Walking down into the town I caught the true smell of woodsmoke and the lingering perfume of cooking and I turned, haunted by a sense of eyes, of faces, of hands on doorframes that vanished into shadows when I looked. Vishnu's Marvellous Magical Magnificent Cat Circus! I cried, ringing my bicycle bell furiously, as much to advertise my poverty and harmlessness as my entertainment. In the Age of Kali the meek and helpless will be preyed upon without mercy, and there will be a surplus of AK-47s.

The cats were furious and yowling in unison when I returned, hot in their cages despite the shade of the awning. I let them hunt by the light of the breaking stars as I set up the ring and the seats, my lamps and sign and alms bowl, not knowing if a single soul would turn up. The pickings were meagre. Small game will be scarce in the Age of Kali.

My fine white Kalki, flowing over the hurdles like a riffle in a stream, it is written that you will battle and defeat Kali, but that seems to me too big a thing to ask of a mere cat. No, I shall take up that task myself, for if it's your name, it's also my name. Am I not Vishnu the ten-incarnated? Are not all of you part of me, cats? I have an appointment down this river, at the foot of that tower of light that spears up into the eastern sky.

Now come, sit down on this mattress - I have swept away the sand and let the lamps draw away the insects. Make yourself comfortable. I would offer chai but I need the water for the cats. For tonight you will witness not only the finest cat circus in all of India - likely the only cat circus in all of India. What do you say? All they do is run in a circle? Brother, with cats, that is an achievement. But you're right; running in a circle, nose to tail, is pretty much the meat of my cat circus. But I have other ways to justify the handful of rupees I ask from you. Sit, sit, and I will tell you a story, my story. I am Vishnu, and I was designed to be a god.

There were three of us and we were all gods. Shiv and Vish and Sarasvati. I am not the firstborn; that is my brother, Shiv, with whom I have an appointment at the foot of the Jyotirlinga of Varanasi. Shiv the prosperous, Shiv the businessman, the global success, the household name, and the inadvertent harbinger of this Age of Kali; Shiv - I cannot imagine what he has become. I was not the firstborn but I was the best born and therein lies the trouble of it.

Strife, I believe, was worked into every strand of my parents' DNA. Your classical Darwinist scorns the notion that intellectual values can shape evolution, but I myself am living proof that middle-class values can be programmed into the genes. Why not war?

A less likely I-warrior than my father you would be hard-pressed to imagine. Uncoordinated; ungainly; portly - no, let's not mince words, he was downright fat; he had been a content and, in his own way, celebrated designer for DreamFlower. You remember DreamFlower? Street Sumo; RaMaYaNa; BollywoodSingStar. Million-selling games? Maybe you don't. I increasingly find it's been longer than I think. In everything. What's important is that he had money and career and success and as much fame as his niche permitted and life was rolling along, rolling along like a Lexus, when war took him by surprise. War took us all by surprise. One day we were the Great Asian Success Story - the Indian Tiger (I call it the Law of Aphoristic Rebound - the Tiger of Economic Success travels all around the globe before returning to us) - and unlike those Chinese we had English, cricket, and democracy; the next we were bombing each other's malls and occupying television stations. State against state, region against region, family against family. That is the only way I can understand the War of Schism: that India was like one of those big, noisy, rambunctious families into which the venerable grandmother drops for her six-month sojourn and within two days sons are at their fathers' throats. And the mothers at their daughters', and the sisters feud and the brothers fight and the cousins uncles aunts all take sides and the family shatters like a diamond along the faults and flaws that gave it its beauty. I saw a diamond cutter in Delhi when I was young - apologies, when I was small. Not so young. I saw him set the gem in the padded vise and raise his cutter and pawl, which seemed too huge and brutal tool by far for so small and bright an object. I held my breath and set my teeth as he brought the big padded hammer down and the gem fell into three gems, brighter and more radiant than their parent.

"Hit it wrong," he said, "and all you have is dazzling dust."

Dazzling dust, I think, has been our history ever since.

The blow came - success, wealth, population strain - and we fell to dust, but Delhi didn't know it. The loyalists resolutely defended the dream of India. So my father was assigned as Help Desk to a Recon Mecha Squad. To you this will sound unspeakably hot and glamorous. But this was another century and another age and robots were far from the shimmering rakshasa-creatures we know today, constantly shifting shape and function along the edge of human expectation. This was a squad of reconnaissance bots; two-legged joggers and jumpers, ungainly and temperamental as iron chickens. And Dadaji was the Help Desk, which meant fixing them and de-virusing them and unbugging them and hauling them out of the little running circles they'd trapped themselves in, or turning them away from the unscalable wall they were attempting to leap, all the while wary of their twin flechette-Gatlings and their close-defence nano-edged blades.

"I'm a games coder," he wailed. "I choreograph Bollywood dance routines and arrange car crashes. I design star-vampires." Delhi ignored his cries. Delhi was already losing as the us-too voices of national self-determination grew loud in the Rashtrapati Bhavan, but she chose to ignore them as well.

Dadaji was an I-warrior, Mamaji was a Combat Medic. It was slightly truer for her than for Dadaji. She was indeed a qualified doctor and had worked in the field for NGOs in India and Pakistan after the earthquake and with Médecins Sans Frontières in Sudan. She was not a soldier, never a soldier. But Mother India needed frontline medics, so she found herself at Advanced Field Treatment Centre 32 east of Ahmedabad at the same time as my father's recon unit was relocated there. My mother examined Tech-Sergeant Tushar Nariman for crabs and piles. The rest of his unit refused to let a woman doctor inspect their pubes. He made eye contact with her, for a brave, frail second.

Perhaps if the Ministry of Defence had been less wanton in their calling-up of I-warriors and had assigned a trained security analyst to the 8th Ahmedabad Recon Mecha Squad instead of a games designer, more would have survived when the Bharati Tiger Strike Force attacked. A new name was being spoken in old east Uttar Pradesh and Bihar: Bharat, the old holy name of India; its spinning-wheel flag planted in Varanasi, most ancient and pure of cities. Like any national liberation movement, there were dozens of self-appointed guerrilla armies, each named more scarily than the predecessor with whom they were in shaky alliance. The Bharati Tiger Strike Force was embryo Bharat's élite I-war force. And unlike Tushar, they were pros. At 21:23 they succeeded in penetrating the 8th Ahmedabad's firewall and planted Trojans into the recon mechas. As my father pulled up his pants after experiencing the fluttering fingers and inspection torch of my mother-to-be at his little rosebud, the Tiger Strike Force took control of the robots and turned them on the field hospital.

Lord Shiva bless my father for a fat boy and a coward. A hero would have run out onto the sand to see what was happening when the firing started. A hero would have died in the crossfire, or, when the ammunition ran out, by their blades. At the first shot, my father went straight under the desk.

"Get down!" he hissed at my mother who froze with a look part bafflement, part wonderment on her face. He pulled her down and immediately apologised for the unseemly intimacy. She had lately cupped his testicles in her hand, but he apologised. They knelt in the kneehole, side by side, while the shots and the cries and the terrible, arthritic click click click of mecha joints swirled around them, and little by little subsided into cries and clicks, then just clicks, then silence. Side by side they knelt, shivering in fear, my mother kneeling like a dog on all fours until she shook from the strain, but afraid to move, to make the slightest noise in case it brought the stalking shadows that fell through the window into the surgery. The shadows grew long and grew dark before she dared exhale, "What happened?"

"Hacked mecha," my father said. Then he made himself forever the hero in my mother's eyes. "I'm going to take a look." Hand by knee by knee by hand, careful to make no noise, disturb not the least piece of broken glass or shattered wood, he crept out from under the desk across the debris-strewn floor to underneath the window. Then, millimetre by millimetre, he edged up the side until he was in a half-crouch. He glanced out the window and in the same instant dropped to the floor and began his painstaking crawl back across the floor.

"They're out there," he breathed to Mamaji. "All of them. They will kill anything that moves." He said this one word at a time, to make it sound like the natural creakings and contractions of a portable hut on a Ganga sandbank.

"Perhaps they'll run out of fuel," my mother replied.

"They run off solar batteries." This manner of conversation took a long time. "They can wait forever."

Then the rain began. It was a huge thunder-plump, a forerunner of the monsoon still uncoiling across the Bay of Bengal, like a man with a flag or a trumpet who runs before a groom to let the world know that a great man is coming. Rain beat the canvas like hands on a drum. Rain hissed from the dry sand as it was swallowed. Rain ricocheted from the plastic carapaces of the waiting, listening robots. Rain-song swallowed every noise, so that my mother could only tell my father was laughing by the vibrations he transmitted through the desk.

"Why are you laughing?" she hissed in a voice a little lower than the rain.

"Because in this din they'll never hear me if I go and get my palmer," my father said, which was very brave for a corpulent man. "Then we'll see who hacks whose robots."

"Tushar," my mother whispered in a voice like steam, but my father was already steadily crawling out from under the desk towards the palmer on the camp chair by the zip door. "It's only a?.?.?."

And the rain stopped. Dead. Like a mali turning off a garden hose. It was over. Drips dropped from the ridge line and the never-weatherproof windows. Sun broke through the plastic panes. There was a rainbow. It was very pretty but my father was trapped in the middle of the tent with killer robots on the alert outside. He mouthed an excremental oath and carefully, deadly carefully, reversed among all the shattered and tumbled debris, wide arse first like an elephant. Now he felt the vibration of suppressed laughter through the wooden desk sides.

"Now. What. Are. You. Laughing. At?"

"You don't know this river," my mother whispered. "Ganga Devi will save us yet."

Night came swift as ever on the banks of the holy river; the same idle moon as now lights my tale rose across the scratched plastic squares of the window. My mother and father knelt, arms aching, knees tormented, side by side beneath the desk. My father said: "Do you smell something?"

"Yes," my mother hissed.

"What is it?"

"Water," she said, and he saw her smile in the dangerous moonlight. And then he heard it, a hissing, seeping suck sand would make if it were swallowing water but all its thirst was not enough, it was too much, too fast, too too much, it was drowning. My father smelled before he saw the tongue of water, edged with sand and straw and the flotsam of the sangam on which the camp stood, creep under the edge of the tent, across the liner, and around his knuckles. It smelled of soil set free. It was the old smell of the monsoon, when every dry thing has its true perfume and flavour and colour released by the rain; the smell of water that is the smell of everything water liberates. The tongue became a film; water flowed around their fingers and knees, around the legs of the desk as if they were the piers of a bridge. Dadaji felt my mother shaking with laughter, then the flood burst open the side of the tent and dashed dazed drowned him in a wall of water so that he spluttered and choked and tried not to cough for fear of the traitor mecha. Then he understood my mother's laughter and he laughed too, loud and hard and coughing up lungfuls of Ganges.

"Come on!" he shouted and leaped up, overturning the desk, throwing himself onto it like a surfboard, seizing the legs with both hands. My mother dived and grabbed just as the side of the tent opened in a torrent and desk and refugees were swept away on the flood. "Kick!" he shouted as he steered the desk towards the sagging doorway. "If you love life and Mother India, kick!" Then they were out in the night beneath the moon. The sentinel unfolded its killing-things, blade after blade after blade, launched after us, and was knocked down, bowled over, swept away by the flooding water. The last they saw of it, its carapace was half stogged in the sand, water breaking creamy around it. They kicked through the flotsam of the camp, furniture and ration packs and med kits and tech, the shorted, fused, sparked-out corpses of the mecha and the floating, spinning, swollen corpses of soldiers and medics. They kicked through them all, riding their bucking desk, they kicked half-choked, shivering, out into the deep green water of Mother Ganga; under the face of the full moon they kicked up the silver corridor of her river light. At noon the next day, far far from the river beach of Chattigarh, an Indian patrol-RIB found them and hauled them, dehydrated, skin cracked, and mad from the sun, into the bottom of the boat. At some point in the long night either under the desk or floating on it they had fallen in love. My mother always said it was the most romantic thing that had ever happened to her. Ganga Devi raised her waters and carried them through the killing machines to safety on a miraculous raft. Or so our family story went.

Copyright © 2009 by Ian McDonald

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details