Added By: illegible_scribble

Last Updated: valashain

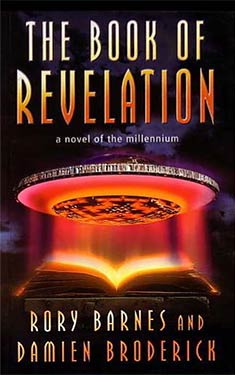

The Book of Revelation: or Dark Gray

| Author: | Damien Broderick Rory Barnes |

| Publisher: |

Fantastic Books, 2010 HarperCollins Australia, 1999 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

My father is the Rev. Daimon Keith. At the age of twenty, he was abducted near a school playground by small gray aliens. Indeed, Daimon was taken up into UFOs not just that once, but from infancy, and over and again. It caused him to devote his middle years to the establishment of the Church of Jesus Christ, Time Traveler, and later Scionetics.

Rosa "Flake" Rosch is a postmodern orphan. She's forgotten her mother, and her notorious abductee father Deems has vanished - again. Dark Gray is Rosa's unreliable memoir of her father's zany life, from his hapless prankster youth in Australia to apotheosis as a UFO guru in the 21st century. It's the story of Rosa's indomitable mother, her weird quasi-brother Ben, Zelda the horsewife, and our whole tormented era, as we blast into hyperreality.

The Book of Revelation was republished as Dark Gray by Fantastic Books in 2010.

Excerpt

November 1975, Melbourne

Daimon regards the invitation with distaste. Dinner at 7:30. So she is actually living with this journalist, this Claude Karlson? The invitation is typewritten on abandoned thesis paper. He has a mind to reply on lavatory paper, but it's hard to write on the stuff without the pen ripping it to shreds. Reluctantly, he sends off an ordinary note: yes, I'd love to come and it would be good to see you again and little Rosa too, and all my love. Signed his goodself.

And what of this Karlson character? Usurper, hack, wordsmith, gentleman of the press. Will he have pressing concerns that prevent his appearance at the dinner table, the better to allow two old chums to reminisce? No such diplomacy is in the offing. Margaret's typewriter makes that clear enough. To meet Claude.

By what extraordinary twist of her retired philosopher's brain, Deems asks himself, does she think he wants to meet Claude? What has he to say to this overweight and ageing Casanova of the tabloids? A cosy little re-union this will be, with Karlson the Obese smirking across the table, leering his ancient roue leer. Deems pictures the scene easily enough, for while my mother's Olivetti has skipped over the gross and antique attributes of the hack Karlson, my father has his informants.

But will Karlson, in fact, smirk and leer? So help me God, Daimon reflects bitterly, there is always the chance that he'll try for a hearty hail-fellow-well-met-have-another-drink bonhomie. Put a chap at his ease. No hard feelings. The luck of the game. Better the smirk! Better the smirk than that breed of superannuated patronage. Smirk or no smirk, Deems is committed to meeting him, pledged by his note of acceptance. And it is right and proper that he should make his acquaintance. This toad is in loco parentis re his daughter, and no amount of slick Latin phrases can take the place of the quick personal once-over.

His daughter! Rosa! What sort of "father" would this hack make for little Rosa? Belay the usurpation of bed and board, what of the natural affection of natural child for natural father? To be abrogated by this churl! And has Karlson himself designs upon the womb that bore Rosa? Does his seed already fall on that fertile ground? These old failed has-beens, Daimon knows, are notorious for last-ditch stands, hopeless attempts at immortality before senility or the grave puts an end to their fumblings. Who knows what scattered tribe of genetically suspect brutes has already resulted from what string of wrecked marriages. Progeny-tested all right; found fertile but wanting. There's the rub. Has a father no rights? Is he to stand idle, Deems asks himself, while mongoloid mini-hacks are thrust upon his daughter as playmates and half-siblings? His informants seem to think this unlikely. Deems can only pray they are right.

The principle informant, Rhys, meets Daimon for lunch on the day scheduled for the dinner. Evidently Rhys knows this Karlson well enough, has his measure. He passes the claret and formulates a strategy. "The thing to go for, young Keith, is the Manly Handshake."

"The manly handshake, you think?"

"The Manly Handshake." Rhys speaks in capitals. "Remember, you are now an Old Friend of the Family. A Manly Handshake is expected of you, I'll show you how later."

The lunch is long and mainly liquid. Afterwards they adjourn to a pub. Leaning against the bar, Deems and Rhys practise the Manly Handshake.

"Look the bastard in the eye, Dave, and grip his hand like a bloody vice."

Rhys's own hand has the texture of sandpaper and the bone-crushing capacities of a pile driver. At least he no longer wears a stockman's hat with dangling corks. They retire to a table, Deems still wincing slightly, and have a few drinks to recover. Louise's name is mentioned. Rhys recalls Sally-Ann, getting her name wrong. They wonder what became of the yapping pug. Deems describes his adventures in Nepal. Cathie's name is not mentioned. The afternoon slips quietly away.

Daimon doodles on a beer mat, giving ears and a grinning mouth to a splodge of spilt beer. Some friends of Rhys's join their table, and the cameraman capitalises on their lunchtime conversation by telling a girl with false eyelashes about the time he climbed a twenty-five thousand foot peak in Nepal, a massive load of media equipment strapped to his back. Total authenticity is achieved by long, agonised attempts to recall individual Sherpas' names. Deems puts a hat on his beer-mat man. The pub begins to fill with drinkers. The leader of Rhys's expedition falls down a crevasse. The level of conversational din rises; the dinner hour approaches.

It won't, Deems supposes muzzily, be too bad. The scene presents itself: D. Keith, Esq. pressing the buzzer, composing himself while footsteps patter down the hall, the door opening to allow the bright smiles, the hug and the statutory one-second mouth-to-mouth kiss, the long march down the hall to meet Karlson who rises from the couch on which he has been taking his ease, the Manly Handshake, this new lover smoothing over any momentary flicker of unease by busying himself with the provision of drinks. And then, of course, the production of Rosa.

Will Karlson bring Daimon's daughter to meet him? Holding her shy little hand? What does Rosa call him? Dad, daddy, Pop, uncle (hardly), Claude? Obviously she calls him Claude. Obviously she doesn't call him anything at all - children of her age can't talk. They chortle and cry. Mewl and puke. Puke and miaow. They do not miaow. Children are not cats. Cats are not dogs. A cat's a cat, a dog's a dog, as the Anglo-American Mr Eliot once remarked, and he had never been to Pinchgut island in the middle of the night. What might he have remarked had he been instead, like Zelda, an Anglo-Indian? Something about monkeys and tigers? Strange gods in sky-chariots? Deems considers himself a man not without culture. He is also, by the time he falls into the passenger seat of Rhys's car, quite drunk. If Deems is not by habit a hard-drinking man, neither is he evasive. He prefers reality, however bizarre. Eight out of ten Australians prefer reality. It's the real thing.

Rhys tells him, "It's only six o'clock."

"Never mind. Drop me on the other side of the park, I could do with some fresh air."

The flat, finally located, is up a flight of stairs: carpeted, potted plants on the landings. Daimon presses the buzzer and prepares to compose himself, but the door opens instantly inwards, its fish-eye gleaming. A large, hairy man in a towel says, "You must be Daimon Keith."

"Er, yes."

"Come in. I can't stop now, I'm talking to Canada. The living room's that way. Be with you in a minute. Margaret's still in the bath."

He gesticulates powerfully down the hall with the telephone. Deems eases his way into the flat, pressing past the man's naked bulk. Karlson smells of soap and after-shave. It is true that he has a weight problem; the towel - loosely knotted over his belly - makes that plain enough. But the bastard looks fit. Fat but fit. And none too ancient, say mid-forties. Vic Thompson's age. Daimon's informants have been guilty of exaggeration. Karlson returns to his telephone, reading from a sheaf of typescript on the hall table.

"Sorry about that. Someone at the door. To continue: R Hawke comma national leader of the Labor party comma today pledged his support for the deposed prime minister comma but called upon the trade union movement to exercise restraint in the face of quotes unimaginable provocation unquote stop new par however at angry meetings in both..."

The carpet in the living room has flecks in it, as if it has measles. Deems sits and regards the measly carpet. The long distance punctuation lesson continues from the hall. From the other direction issue plashings and splashings.

Margaret at Bath. Naked, wet, slippery. Times were when he would have joined her. Both of them together - a tangle of limbs, sliding about, laughing. But what rights now the ex-lover? Ex-cohort, to be exact. It wasn't any one-night-stand or dirty weekend, Karlson, you old fraud. Hell no, boss, me and Margaret were like two goddamned peas in a pod. Long before you ever hit the goddamned scene. Yes sirree. But what rights now?

A good question, no doubt, for the editor of Swinging Etiquette. Are unmarried mothers in South Yarra flats allowed to walk around stark naked in the presence of previous lovers? May they receive old Friends of the Family in their bathrooms? Ms Margaret Rosch will be at bath on Thursday the Tenth at 8.00 am and requests the pleasure of your company. R.S.V.P., B.Y.O. Soap. Ha, ha. Probably not. However, Deems tells himself sagely, we do live in an age of shifting values. Prudery is definitely on the run. Unmarried mothers may, if they wish, entertain previous lovers in a slip or chemise without resorting to the more formal gaberdine raincoat and wellington boots normally worn during the cocktail hour when chatting with those unacquainted with their favours. Oh, yes, indeed they may.

"Darling, have you seen the body lotion?"

"It's not darling, it's me. Darling's on the phone."

"Deems. Already. How are you?"

"Bonzer. Yourself?"

"Fine. How was India?' Deems finds this line of enquiry somewhat tangential. What about the come-on-in-and-see-me bit, eh? 'Have you got a drink?"

"No."

"There's beer in the fridge and other things on the sideboard." Quite so, Daimon has already noticed the quantities of sweet vermouth, a detestable potable.

"Good," Deems says. "Want anything yourself?"

"Not at the moment."

Why not? What's wrong with a companionable drink in the bath? Aren't we allowed the fruits of Western Decadence any more? Condemned to drink alone, Deems rips the top from a tin of beer and reconsiders the carpet. The flecks aren't so much measly as poxy. A pox on this inhospitable steading. Shouldn't he go in and see Margaret, do the civilised thing, sit on the elegant little gilded stool in front of the wall-sized mirror, toss one leg over the other while engaging her in witty conversation?

The splashing continues. Deems makes his way in its general direction and appears nonchalantly in the bathroom doorway. My mother lies full length in the water - knees, neck, nipples clear of the foam. Her hair is piled on top of her head and the heat of the water has brought a maidenly flush to her cheeks. She doesn't look totally welcoming. To put her at her ease, Daimon leans against the door jamb and opens the witty conversation.

"G'day."

"Hello," she says.

From the direction of the front door they learn faintly that militant union action can be expected comma but with current public reaction yet unclear comma it seems that the governor general comma sir John Kerr comma that's k for kitchen e for elephant r for robert r for robert and so on and so forth without pause or let or hindrance.

"What's all that about?' Deems asks, indicating the source of the monologue with his thumb.

"Claude's a stringer for some Canadian papers."

"Repairs their tennis rackets and such like?"

"Keitho, are you drunk?"

"Never touch the stuff. I brought this for you."

Deems offers her a swig from his beer can. She declines, looking fairly fierce lying half-submerged, a sort of Loch Ness monster stranded in a tub. Her nipples accuse him.

"How's Flake?' he asks.

"Who?"

"Flake. As in soap-flake, as in Lux soap, as in Luxemburg, as in Rosa... My daughter," he adds helpfully.

"You are drunk."

"Well, how is she?"

"She's well."

"Oh, good." Deems searches the bathroom for the elegant little stool in front of the wall-sized mirror. Strangely, it is missing. Some bastard has abducted the mirror. This poses a problem: there are two, and only two, possible places to sit down - the edge of the bath and the lavatory. The first, though more elegant, is a trifle too close to the Loch Ness beastie for comfort. The second raises obvious questions of decorum and taste: Deems thinks it unlikely that the editor of Swinging Etiquette would recommend that particular perch as the essence of chic. Even if a man were wearing his goddamned jeans. Would that that slim volume were written and lay to hand. Alone and all unaided, however, D. Keith's lightning computer-trained brain solves the dilemma. The lavatory is equipped with a lid. Shut the lid and gracefully sit on that.

A rifle shot ricochets about the bathroom.

"God almighty! We'll all be killed."

"Deems, for Christ's sake--"

"The bloody thing's snapped."

"I can see that. It's not meant to have people crashing down on it. Get off, you great oaf."

Easier said than done. No sooner has Deems managed to ease his weight off the newly bifurcated plastic than the two halves spring back together, viciously gripping his left buttock.

"Help! Crabs!"

"Deems!"

"It's got me, the bastard."

Attempting to rise only increases the monster's tenacity. With a yelp he crashes back to the pedestal. This time the lid splits clean in half. The report echoes like a second gun shot.

"Hot-dang," Deems drawls, "that sure was one hell of a privy. Ain't rassled me an ornery ole privy like that since I was a kid back in the goddamned Rockies."

Deems arises and surveys his vanquished adversary. Each half of the seat hangs on its respective hinge. In death the lavatory seat looks meek and kinda lonesome, but the pain he still feels serves as a grim reminder of its former ferocity. Daimon undoes the buckle of his belt and lowers his pants to check the extent of his maiming. A nasty red V disfigures his lily-white cheek.

"You sure was one helluva pain in the ass," Deems quips.

"Deems has just broken the dunny seat."

He looks up from his medical examination. The stringer has arrived in his towel.

"Howdy, stringer," Deems says, extending his right hand while hanging onto his pants with his left. "Sure is glad to meet you, boy."

The stringer is slow to react, but he puts out his mitt. Deems grabs it, as he and Rhys have practiced, high up above the knuckles, and does his friend proud with his Manly Handshake. Yes sirree, all the strength of a born backwoods privy rassler goes into that there handshake. The stringer winces.

Copyright © 1999 by Damien Broderick

Copyright © 1999 by Rory Barnes

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

Full Details

Full Details