Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

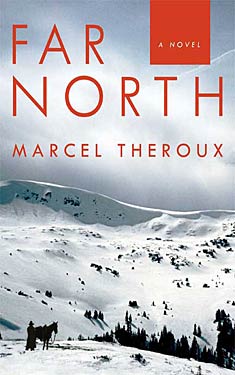

Far North

| Author: | Marcel Theroux |

| Publisher: |

Faber and Faber, 2009 Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Climate Fiction (Cli-Fi) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

2009 National Book Award Finalist

My father had an expression for a thing that turned out bad. He’d say it had gone west. But going west always sounded pretty good to me. After all, westwards is the path of the sun. And through as much history as I know of, people have moved west to settle and find freedom. But our world had gone north, truly gone north, and just how far north I was beginning to learn.

Out on the frontier of a failed state, Makepeace-sheriff and perhaps last citizen-patrols a city’s ruins, salvaging books but keeping the guns in good repair.

Into this cold land comes shocking evidence that life might be flourishing elsewhere: a refugee emerges from the vast emptiness of forest, whose existence inspires Makepeace to reconnect with human society and take to the road, armed with rough humor and an unlikely ration of optimism.

What Makepeace finds is a world unraveling: stockaded villages enforcing an uncertain justice and hidden work camps laboring to harness the little-understood technologies of a vanished civilization. But Makepeace’s journey-rife with danger-also leads to an unexpected redemption.

Far North takes the reader on a quest through an unforgettable arctic landscape, from humanity’s origins to its possible end. Haunting, spare, yet stubbornly hopeful, the novel is suffused with an ecstatic awareness of the world’s fragility and beauty, and its ability to recover from our worst trespasses.

Excerpt

Chapter One

Every day I buckle on my guns and go out to patrol this dingy city.

I've been doing it so long that I'm shaped to it, like a hand that's been carrying buckets in the cold.

The winters are the worst, struggling up out of a haunted sleep, fumbling for my boots in the dark. Summer is better. The place feels almost drunk on the endless light and time skids by for a week or two. We don't get much spring or fall to speakof. Up here, for ten months a year, the weather has teeth in it.

It's always quiet now. The city is emptier than heaven. But before this, there were times so bad I was almost thankful for a clean killing between consenting adults.

Yes, somewhere along the ladder of years I lost the bright-eyed best of me.

Way back, in the days of my youth, there were fat and happy times. The year ran like an orderly clock. We'd plant out from the hothouses as soon as the earth was soft enough to dig. By June we'd be sitting on the stoop podding broad beans until our shoulders ached. Then there were potatoes to dry, cabbages to bring in, meats to cure, mushrooms and berries to gather in the fall. And when the cold closed in on us, I'd go hunting and ice fishing with my pa. We cooked omul and moose meat over driftwood fires at the lake. We rode up the winter roads to buy fur clothes and caribou from the Tungus.

We had a school. We had a library where Miss Grenadine stamped books and read to us in winter by the wood-burning stove.

I can remember walking home after class across the frying pan in the last mild days before the freeze and the lighted windows sparkling like amber, and ransacking the trees for buttery horse chestnuts, and Charlo's laughter tinkling up through the fog, as my broken branch went thwack! thwack! and the chestnuts pattered around us on the grass.

The old meetinghouse where we worshipped still stands on the far side of the town. We used to sit there in silence, listening to the spit and crackle of the logs.

The last time I went in there was five years ago. I hadn't been inside for years and when I was a child I'd hated every stubborn minute I'd been made to sit there.

It still smelled like it used to: well-seasoned timber, whitewash, pine needles. But the settles had all been broken up to be burned and the windows were smashed. And in the corner of the room, I felt something go squish under the toe of my boot.It turned out to be someone's fingers. There was no trace of the rest of him. I live in the house I grew up in, with the well in the courtyard and my father's workshop much as it was in my childhood, still taking up the low building next to the side gate.

In the best room of the house, which was kept special for Sundays, and visitors, and Christmas, stands my mother's pianola,and on it a metronome, and their wedding photograph, and a big gilded wooden M that my father made when I was born.

As my parents' first child, I bore the brunt of their new religious enthusiasm, hence the name, Makepeace. Charlo was born two years later, and Anna the year after that.

Makepeace. Can you imagine the teasing I put up with at school? And my parents' displeasure when I used my fists to defend myself?

But that's how I learned to love fighting.

I still run the pianola now and again, there's a box of rolls that still work, but the tuning's mostly gone. I haven't got a good enough ear to fix it, or a bad enough one not to care that I can't.

It's almost worth more to me as firewood. Some winters I've looked at it longingly as I sat under a pile of blankets, teeth chattering in my head, snow piled up to the eaves, and thought to myself, Damn it, take a hatchet to it, Makepeace, and be warm again! But it's a point of pride with me that I never have. Where will I get another pianola from? And just because I can't tune the thing and don't know anybody who can, that doesn't mean that person doesn't exist, or won't be born one day. Our generation's not big on reading or tuning pianolas. But our parents and their parents had plenty to be proud of. Just look at that thing if you don't believe me: the burl on the maple veneer, and the workmanship on her brass pedals. The man who made that cared about what he was doing. He made that pianola with love. It's not for me to burn it.

The books all belonged to my folks. Charlo and my ma were the big readers. Except for that bottom shelf. I brought those back here myself.

Usually when I come across books I take them to an old armory on Delancey. It's empty now, but there's so much steel in the outer door, you'd need a keg of gunpowder to get to them without the key. As I said, I don't read them myself, but it's important to put them aside for someone who will. Maybe it's written in one of them how to tune a pianola.

I found them like this: I was going down Mercer Street one morning. It was deep winter. Snow every where, but no wind, and the breath from the mare's nostrils rising up like steam from a kettle. On a windless day, the snow damps the sound, and the silence every where is eerie. Just that crunch of hooves, and those little sighs of breath from the animal.

All of a sudden, there's a crash, and a big armful of books flops into the snow from what must have been the last unbroken window on the entire street until that moment. The horse reared up at the sound. When I had her calm again, I looked up at the window, and what do you know, there's a little figure hang-dropping into the books.

He's bundled up in a bulky blue one-piece and fur hat. Now he's gathering up the books and fixing to leave.

I shouted out to him, "Hey. What are you doing? Leave those books, damn it. Can't you find something goddamn else to burn?"—along with a few other choice expressions.

Then, just as quick as he appeared, he flung down his armful of books and reached to draw a gun.

Next thing, there's a pop and the horse rears again and the whole street is more silent than before.

I dismounted, easy does it, with my gun drawn and smoking and go over to the body. I'm still a little high from the draw, but already I'm getting that heavyhearted feeling and I know I won't sleep tonight if he dies. I feel ashamed.

He's lying still, but breathing very shallow. His hat came off as he fell. It lies in the snow a few steps away from him, among the books. He's much smaller than he seemed a minute earlier. It turns out he's a little Chinese boy. And instead of agun, he was reaching for a dull Bowie knife on his hip that you'd struggle to cut cheese with.

Copyright © 2009 by Marcel Theroux

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details