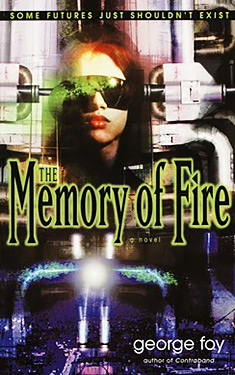

The Memory of Fire

| Author: | George Foy |

| Publisher: |

Bantam Spectra, 2000 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In a dark and not-so-distant future, whole populations are addicted to virtual sensation--and vast bureaucracies are using deadly force to rid themselves of troublemakers. Within this world, small, self-contained communities--called nodes, or cruces--live in an anarchistic freedom that threatens organized society. This is the world of accordionist and composer Soledad MacCrae.

When the cruce of Bamaca on the South American coast is destroyed, Soledad flees to northern California in search of a Yanqui node to give her refuge. But terrifyingly realistic dreams of her old city intrude on her peace. It soon becomes clear that Soledad's visions of her doomed home have somehow turned into a black prediction of how the bureaucracies will wipe out the American node.

Now, to save her new refuge, Soledad must uncover the deadly secret that lies at the heart of her old life, particularly her passionate love affair with rebel poet Jorge Echeverria, whose incendiary poems she once set to music. For music is the final key, not only to the bureaucracies' deadly plans, but to the ultimate mystery of her own survival.

Excerpt

She knows them by color, she has seen these fires so many times, seeking out the grave robbers, the emerald poachers, the gold smugglers, the Adornista guerrillas they are not affiliated with. Now the flames open like mouths in the direction of the garbage wall of Ensevli; it is one of two ways the army can come at the cruce from the land, if you rule out the volcano, as everybody does.

She stabs her heels into the mattress and bends her knees, sliding herself deeper under the sheets. She should crawl out of bed and get dressed but she has never seen the fires so close. In this she is like a town dweller who does not walk in jungle and knows only from the zoo that glow of pink at the corner of a panther's mouth or the splinter of coral when a cloud viper smells prey with its tongue. This morning, though, violence in all its colors has broken out of the selva without notice. Despite the panic rinsing the inner wall of her chest, she lists the explosions rising half the height of her window: scarlet with a flash of amaryllis, framed by oily black smoke streaked with platinum, of RDX explosive from the howitzers; silver, that even at a distance can visit your pupils with pain, from phosphorus shells.

Worst is the napalm, shifting curtains of jellied gasoline stuck horribly to the fractal rooflines; napalm like lava stolen from the volcano's crater, napalm so richly orange at its center it seems it must ignite even things it does not directly touch--which she believes, in any case, to be how it works. Over everything, lit by the fires that created it, the lighter ash of her cruce burning; rising in the dawn breeze till it mingles with the wisp of steam always curling like a lost thought from the summit of San Isidor.

Her head throbs. Her hands are clamped to her ears so hard the palms mash the cochleas as she tries to dampen the noise fire makes. The blast that comes after the red color is loudest, it literally shakes this crooked apartment the way a hound would shake a rabbit, pressing the very air from her chest. But all the other noises--the ripple-smack of napalm, the accelerating run and thunder from the jets, the fast tom-tom of helicopters--weave in and out of each other, crescendo, diminuendo, to create a flurry of sound-fists punching inside her to the place where music is made, and finally clinching cold around the flora there. It seems impossible that so much noise could cram itself through her narrow window in this tenement by the old fishing harbor, a full kilometer from Ensevli. On a normal day you can hear a thousand different noises come through those louvers: the middle-C clink of terra-cotta coffeepots, the rukkling of doves, cats mewing, the conspiratorial whisper of sea wind, the thud of fish boxes, the coughing of a smuggler's launch, the high-seventh of Cloodine calling her daughters; and always, even at dawn, the friction of requinto guitar, a voice moving into song, sad or teasing or angry, the rhythm of bombo drumming held back just the space of a laugh. Yet even those memories add up to zero compared to the chaos of sound now coming at her through the same window. And finally it is the contrast between her lazy mornings and what woke her today that causes her to scream, so loudly it tears ridges in her throat, hands crushing her ears harder to hold the scream in and the noise out but it doesn't work, the noise keeps coming, red-yellow-orange. She twists away from the window and falls to the floor, spraining her lower back.

The pain is hard and clean as a fisherman's knife and it slices through the shock that noise brought. She sits up, grabbing at her spine. The tiles of the floor are the hands of stone corpses on her buttocks. Dolores, she thinks, and part of her mind is amazed that it took her so long to think of anything but fire, and part of it finds that commonplace. She sprints toward the hallway, away from the window, slamming the door behind her.

The noise is still infernal here but it's half what it was in her bedroom. She stumbles through the dark to Dolores's room. This part of the apartment faces the ocean. Curtains dance as the humid and fish-smelling wind pushes through the window. She finds herself wanting to shriek at the breeze, curse it into silence for blindly, repetitively, doing what it always does, when fire is now so close. She actually tries to yell, only to find that her mouth is already open, and she has never stopped.

Anyway, the bed is empty, the blanket flat. The bottle of kohl Dolores paints her eyelids with stands open on the ledge. Behind the breakwater, the bay has gone the sultry indigo it turns just before sunrise, and the sun itself, invisible below the horizon, has touched its own match to the cumulus clouds coasting west on the Trades; but this fire is distant, as light as a girl's blush and, above all, silent.

A jet screams over the dovecote, banking jerkily, climbing more like a geometric expression than a flying thing. Its wings, too, turn rose as the sun's rays catch them. She swivels in the tremble of afterburners, fumbling for the phone. It is dead. It didn't work well at the best of times and now they must have cut the lines.

But it bothers her, for she cannot talk to Jorge, and one of the first people they will want is him. With a wash of warmth to her chest--from shame that it took so long to make the equation come out--she repeats it to herself: "They will want him first."

Back in her room, her eyes deliberately avoiding the window, she puts on earrings--unmatched balsa birds, a vulturine parrot, and an agobequi. She can't find a matching pair from her drawer but maybe this is not so important given the end of everything. She picks up her accordion case. The heavy instrument wrenches her twisted muscles and she gasps. It's an indication of the bad effect of too much noise on her that she is halfway to the front door before remembering that she is naked as a porpoise, except for the earrings; but already her mind was at Pytagoro's Cadillac, where Jorge was going last night, where he has tended to spend all his nights since they stopped spending nights together. She throws on the long peasant skirt she wears to perform, a loose blouse, she has no time for sandals or underwear. Some perverse nook of her psyche whispers, among all the noise, You're doing it because he likes you without knickers, while another segment of her brain replies, Nonsense.

The tenement feels empty. Maybe that is because noise still drowns out the details of sound that are the baseline of life in this place. In the dark stairwell the concussion of explosions has shaken dust from cracked walls and ceilings. Her bare toes sink into grit where it lies in drifts against the tiles.

Human voices on the second landing squeeze through gaps in the shellfire. The door to Cloodine's flat is ajar. Soledad pushes it open. Cloodine huddles in the archway of the next room, the correct position for earthquakes. Her daughters squeak under her sheltering and ever-pregnant stomach; the little boy shrieks in her arms. "Jako," Soledad yells at her, "Where's Jako?" Thinking, Cloodine's new boyfriend should be here to shelter her from this. In the sheen of a propane lamp the whites of Cloodine's eyes are like reflections of a new moon; she gestures at the coffeepot, mutely offering a tinto. The reflex of hospitality is all she can make work for her now. Soledad stares at them for another second or two, feeling under her panic a new distress boiling for the kids, so ridiculously small and soft. But in the end she owns nothing to help them with, no words to comfort them from the direction she is going. Anyway they all knew this would happen, sooner or later.

At least there is no shelling in the heart of this quasi-independent city-state they call the cruce. On the Corniche, the harbor road, people lurk in the purple light, staring upward at flashes of fire reflected from the buildings. A gang of emerald poachers carrying shotguns and machine-pistols moves disorderly but fast down the Corniche, toward Ensevli. A smuggler's boat revs huge gasoline engines at one of the piers while men and women chain-load crates into its cramped hold. Still bartering, she thinks in disgust, still running contraband while the cruce burns, although how they will get around the frigate now blocking passage across the harbor entrance she has no idea.

A Cadillac-bar owner is padlocking his shutters. Soledad starts to run, the accordion case knocking painfully at her thigh, because Pytagoro might be closing, might already have closed due to the attack, and then she will have no idea where Jorge went. He would never go back to des Anglais in the midst of this. As she rounds the base of the disused lighthouse she sees kerosene lamps shining like gentle quasars under the canopy of Pytagoro's, people moving darkly inside. A fisherman she has never met offers in courtly terms to take her offshore till this is over. Afterward, he says, they will go to Isla Cythera and screw in the shallows and make many babies. Half of her wants to split off from the rest and get in his rotten sloop, so badly would she love to leave behind this noise and the bitter smoke of devastation. The other half tells him to fuck off. The fisherman shakes his head, looks down the quay for another client.

Her breath is almost gone by the time she gets to the Cadillac. They have closed the glass doors that usually are shut only in the rainy season and when she pushes through them she understands why: the heavy glass muffles the explosions without and there is actually something to listen for inside, nothing more than the lyrics of people arguing and the rasp of requintos and a harp, it is so normal for Bamaca that she would never ordinarily notice; but this morning it pushes tears into her eyes and strains her esophagus at the thought of how much she loves this town.

A dozen people live in caves the cigarette smoke makes in the umber gloom of kerosene lamps. It is hard to distinguish who is Jorge and who is not; most are older men and they all smoke and many of them play dominoes, as Creoles tend to do in times of mourning. Several sport the same shaggy brindled sort of beard that Jorge wears. One wears Arab robes and turns away from her as she comes in. No one looks up when she calls. She stashes her accordion under the Cadillac itself--the two chopped-off halves of a Coupe De Ville, all gleaming and chromed, that such bars mount against the wall as a pulpit for casse-co jockeys--and walks among the tables to Pytagoro's corner. The men's eyes touch her as she moves. She is conscious of her thighs rubbing under the skirt, as if the men could know her nakedness in the heightening of senses associated with peril.

Pytagoro plays dominoes alone. He racks up the bones, spreads them expertly on the table, shuffles them again. He keeps his eyes on what he is doing as she comes near.

"Have you seen him, Pytagoro?"

"Qui?"

"For God's sake!"

He motions to a chair, a grandiose gesture that mocks as it invites. She does not sit.

"Play Mericain with me."

"I have to find Jorge, they--"

"Play with me, Soledad."

"Damn it, you know what they'll do to him!"

Pytagoro looks up. He holds his head sideways, like a curious rooster. He has large eyes with stained whites and a giant Adam's apple and all his various orbs pop as if pushed by some force bottled up within. His nose is hooked and fleshy; hairs an inch long curl from its nostrils. His lips are sculpted like the bank of a river in spate. A basuko pipe is stuck, flotsamlike, between.

The mathematical clicks of the bones resound clearly above the music, and the gunfire.

"Play," Pytagoro says. "The world has its period, non? And today the cruce is its coño." His laugh winds up, a bus changing gears underwater. He wipes a tear from his left eye. "If you win, I'll tell you where he is."

"Isalop!" she hisses. Bastard. His lips stretch. Then she does sit down, keeping her knees locked together, as if to contain the rage expanding quick as one of those RDX fires. It is useless to argue with Pytagoro at the best of times, and the contrariness that is the prime expression of his personality seems to have tripled now that the cruce is burning around them. She is about to argue anyway, it's all so ridiculous. Then she shrugs, thinking, Mericain will take only four minutes to play.

And Pytagoro, because of that very contrariness, will keep his most inane promises.

She selects seven of the ebony slabs from the pile. A light hand, she can tell immediately: a paired six, three deuces. Pytagoro slaps down a six-five, she follows with a five-two. They play fast, as is the custom, cracking the tiles like rimshots on the zinc. Lamplight rolls shadows across their hands. To her surprise Pytagoro is dry of bones for her last two deuces and she wins the first game. Two, then five men stroll over to watch. During a lull in the shellfire a heavy machine gun opens up, its explosions more regular, deliberate; and the requinto player shifts to follow the rhythm the M-60 makes, a 42 rhythm, somehow she and the bar owner slip into the same meter, slapping the bones bom, bom-bom-bom, and she knows the rhythm even before she consciously recognizes the tune, boom bu-boom, bom-bom, boom, boom (boom), it's the exact beat of "Si mou estoma fue un chien":

If my stomach was a dog,

I would walk it through the halls

where you had been

to catch your scent.

If the world was a knife

I would cut the sky

and draw no blood, no,

nor morning either;

ah, but of these girls

who wander through

their tunnels in the rain,

tell me

how many of them

cradle my heart

the way a tree grows around

a bullet?

And it's as if the verses are claws that rip at her because they are Jorge's words; just as the notes are hers, notes that spilled out of the Fourneaux-Dallapé accordion now locked up and mute under the dark Cadillac juke. She misses a crucial set and loses the second game. Trying to regain control over her thoughts, she bums a butt from Pytagoro's pack, her fingers trembling slightly as she lights it, using fire from a votive Yemanja-Marie in the corner; but the jag of tobacco does not help. The bar owner is one slab down on her from the outset of the third game, and he plays two blanks in a row and wins the match.

She gets to her feet, still trembling. "So?" she rasps. Pytagoro looks up at her for the second time this morning, and says nothing. She remembers how much he loved even the news of disaster; she can tell from the salience of his eyes how much more he adores the real thing. "Isalop," she hisses at him again. She walks under the juke and carefully lifts the accordion. The M-60 is silent now, and the rhythm of other weapons seems to have altered in undefinable but crucial ways, as if they had switched from her 68 merengue to an earlier dance where music had not yet been refined from the lusts and wounds that fueled it. The players have dwindled into improv, letting a scrape of harp keep the beat. "Play with us, Soledad?" the requinto player calls softly, jerking his head vaguely upward, "play against this," but she shakes her head, surprising herself. Before today she always agreed to play--it was the path of least resistance for her, and today you would think it that much more tempting--but she goes to the door. "He went to Legliz," the Arab calls as she goes, and she spins, cracking the glass with her thick instrument case.

She knows this man. In earlier, happier times he was in love with her, and followed her around this enclave like a lost duckling. He closes his eyes as if to disavow the information he just imparted.

Pytagoro, in the corner, is laughing so hard now the tears make snail paths down his cheeks.

"He went to the convent, non? Que tragédie." And Pytagoro is shouting against renewed rocketfire now, sobbing openly, he is so thrilled with himself, "in the autumn of your life, in the agony of this cruce, to seek refuge with the sisters of craziness. Non?"

Once outside she stares up at the heights. From this angle Ensevli and the eastern portion of the cruce are hidden by the Cadillac as well as by the row of bars, brothels and godowns it is set within. Teton Hill, with Bidonville rigged about its base and Barrio des Anglais higher up the northern flank, is clearly visible. At the top, looming like a guilty conscience, the barbicans and crenellations of Legliz girdle the yellow limestone walls of the convent and finally the white marbled towers of the church of Santa Karen.

The clock of the fishermen's chapel reads 5:53. From this perspective the sun is just licking the horizon, but at the altitude of the convent it has become day. The embrasures and bailey glow red as arterial blood and even the cold ash gullies of the volcano seem to retain warmth in the fresh illumination.

She walks faster, pushing through the air-shocks of shellfire, across the Slave Market--and she was wrong about no shells hitting the cruce's center. Because Lo Pano is gone. The crazy tower that once bore countless Udine boards, marquee signs and ticker-tracks, all wired together and hung anyhow to mark the twenty-four-hour barters that were sign and center of the cruce's life, has been blown into a tangle of steel and wiring and charred wood scattered like an abandoned children's game over five hundred square meters. She has to tread carefully to avoid stepping on strange chunks of motherboard and glass. A wedge of Udine still displays earlier exchanges: TOSHIBA-TRANSCOM PARALLEL DRIVER, 270 BARTER-CHIPS; MANIOC, 12 CSAC; GM 12-V STARTERS, 22 CAYMANS-PIÈCE. But nothing is left of the Flash Shack where they kept the terminals and sat-relays that talked to cruces in Brazil and even North America.

Now the only activity is like hers--hurried, avoiding, furtive. A boy picks through smashed circuitry among the splintered struts. Men grunt carts toward shelter, or hustle gaggled families away from the sound of artillery. It is hard to drag the Fourneaux-Dallapé on the level bricks of the market, harder still to walk uphill on the cobbles of the convent road. The muscles of her lower back seize up slightly every time she takes a step. Her bare feet bruise on the unyielding stones. Sweat stings her eyes. She has a weird, airy thought that maybe she got all of this wrong. After all, she made a big mistake once about Jorge's aptitude for fidelity, so maybe she's wasting her time worrying about his ability to save his own life. She recognizes this as a notion that might make sense on a normal day but does not necessarily apply when fire is all around them. And it begs the question of what she would do if she did not have to look for him.

After the road splits off for des Anglais its uphill spur becomes a dirt track where the Bidonville people pried up stones to build walls for their shacks. Children coast toward the harbor on homemade go-carts. Families wheel mopeds piled with pots, chickens, bags of food. Donkey carts and mototaxis creak under cargoes of bootleg pinga, spindles of pirated software, counterfeit Kogi stelae, all the industries of Bidonville. She dodges and pushes against a flow of people moving downhill. The noise is much stronger up here, though this part of Bidonville is probably only a little closer to Ensevli than her apartment was; it's just that, with altitude, there is less to break the sound.

Far more smoke is visible now, it climbs overhead in the light wind and then folds back toward the fishing harbor in backdraft from the perkling crater. Ash falls in gray flurries. She can smell the smoke's sour breath, feel grit rasp the back of her mouth. A condor flies overhead, or something like; it has the shape, the cruel bill, the spread-feathered wings, but it is too big and its angles too precise and anyway condors don't have tiny propellers at their tail and slits in their resin fuselage out of which blare overamplified, discordant voices. She drops the case and slaps her hands against her ears again until the condor passes.

As she takes her hands from her ears and drops her eyes toward the next corner she notices a woman standing still in a glassless window to her right. She has hair like polished coal, tied rigorously back; a crimson shawl, a worried expression, big hands ever ready to catch a child should she stumble. And Indio cheekbones, gray eyes hammocked on wrinkles, and the overpainted mouth that sang Soledad lullabies from the jungle. A squat woman in a cheap sharecropper skirt. Her mouth frames the single word: "Reviens."

Soledad closes her eyes tightly. "Lombuage," she tells herself firmly--an illusion. Maria Gisela has been dead almost three years now. When she opens her eyes again the apparition is gone. She pushes it from her mind, thinking only, It's normal that tensions pulling so hard in such different directions in her brain should leave areas of slack where dreams might wander in. She starts walking again, slower. Her legs drag backward toward gravity, it's as if they avoid taking a path other than that of headlong flight. She forces herself uphill anyway, stopping for breath at first every minute, then every thirty seconds, shifting the accordion from shoulder to shoulder but resuming her climb every time till she has reached the last stretch of path at the top of Teton.

It was the song that made her do this, she decides. The song in the Cadillac. Not only because it reminded her of Jorge but because it connected through him to his daughter. And that, in turn, like an electrical current flowing into everything it touched, lit up the memory of the two kids nestled soft as ducklings under Cloodine's skirts, and also what she once felt for Jorge; and all of it has fused like shorted wiring inside her.

Because if Dolores has not already run for safety on a fishing sloop then she will be with her father. Or at least Jorge will know where she is, and then Soledad can drive them both toward safety, away from the heights. And now it is anger, rather than an inability to think of anything else worth doing, that drives her upward again; fury because he has no business coming up here, rage because she should not be reacting this way, squandering the precious division between them here where the explosions are louder, much louder, and from a different direction.

She stops abruptly.

This curve in the track is still hemmed in by shacks, but now she stands almost under the deep bastion of the convent.

Her wrenched muscles burn like a red-hot pipe buried in her lumbar region. Despite her caution she must have cut her foot in the Slave Market because her left footprint is accented by damp brown stains. Sweat drips down her earrings onto her collarbone; it runs between her breasts; it has soaked her pubic hair and drips down her inner thighs. Left hand at left ear again to muffle the renewed volume, right hand grasping the strap of the accordion case, she limps to the corner, to the earthen square before the convent's main gate, where she can see better.

The heights of Teton are too steep here to build more than one layer of shacks on a given level. You can look through gaps in the huts above the rows of similar huts tumbling like dice to the des Anglais district, and farther, past the Slave Market and the fishing harbor to the Walled City, and the dark facades of the Customs building where the General Staff and their F2 advisers must be watching through binoculars, directing over radio and computer links the artillery strike on the cruce. But what she stares at is the two brigades almost next to her: guaqueros, grave robbers, she knows some of them from the Cadillac they frequent. Some are digging a short trench with gold diggers' picks while others set up green tubes, three-inch mortars out of crates still marked CORPO DE EXERCITO XVIIBOA VISTA; pointing them north toward the coast road, where a column of smoke rises in front of armored personnel carriers lined up like matte green beetles at the approach to the cruce, coming from the opposite direction from Ensevli--a flanking action that bypasses the City of Boats but will squeeze the rest of the cruce like a vise.

Beside the guaqueros a tall man with a white beard, a Ping-Pong paddle in one hand, waggles his arms ritually. "No, no, no," he scolds, "left engine, left engine!" A policeman's hat is perched on his head but there are no flics in the cruce, anyway he wears the light blue smock of a Legliz patient. His directing of air traffic seems to work, in the sense of making things happen; where he was pointing, a red mushroom grows fast in the heart of des Anglais. It carries on its mottled skin bits of stone, mirror, tile, a car door. The mushroom becomes the size of a small house, then bursts, turning to smoke and sound and a gust of air that physically pushes Soledad back a pace, fanning her hair behind as if she stood in the first swipe of a hurricane.

Debris patter. One of the guaqueros yells at her. She cannot make out his words through the numbness of her ears. His intent, though, is transparent enough. He is waving at her, then at the convent postern, linking the two in time and space so she will get the hell into shelter before the hostile artilleryman tracks closer--or perhaps it is his own weapons he wishes to protect her from. For the other guaqueros, startled by the explosion, have triggered a mortar aimed at too acute an angle. Its projectile arcs almost directly above them and lands closer to the guaquero positions than the earlier shell.

Another backdraft happens. Overhead, a "condor" swoops from behind the convent tower, sunlight flashing in the lens of its betacam. A whup-whup-whup of engine noise rises from behind the clerestory. She picks up the Fourneaux-Dallapé, holding it like a puppy in her arms, and runs across the earth of the square under the swordlike shadow of a giant green chopper gliding around the northern slope of Teton, the whup-whup suddenly louder than fire or jets--and finally under the ocher walls of the convent bastion rising fifteen meters overhead, into the black pool, the cool, the humid night behind the postern.

The walls of Santa Karen were built of mortar mixed with bulls' blood to withstand the agitprop and sappers' charges of pirates. They are five meters thick. The rare windows are only a few centimeters across so cannonballs cannot get in. The entrance tunnel runs left and right. She turns left toward the main body of the church. Within five paces the roar of chopper and the crashing of shells are wrapped in stone, isolated from her ears. After fifty paces they are gone.

The convent smells of incense and ether and herbs like verveine and sauge that the nuns use in their ministrations. The light splashing from the gate fades behind her. The corridors are of brown stone and whitewash, but with no power for lightbulbs the colors soon are folded into charcoal and then black--until the process is reversed, here by a stone lamp set in a niche, or there, by an open door. A deep-sea glow illuminates portions of the rooms behind these doors. As she passes she sees robed nuns tending stacks of ancient murmuring televisions. The huge sets are lined up before rows of blue-smocked men and women. She can tell when she nears one of these rooms, not only by the glow but by the simple rhythm scratching out of the deadness of stone. The nuns all carry instruments, usually marimbas or tom-toms, on which they cheerfully bat the different timings of their therapy.

One sister stands apart from her patients at the third therapy room. Soledad slips inside to ask if she has seen Jorge or any other crucistas. The nun puts a finger to her lips, then goes back to scratching at the surface of a rasp, matching her rhythm to that of a highly charged dénouement in a Mexican soap opera. Soledad stares at the nun, attracted despite herself by the woman's absorption in a different discipline. She wonders for a second if she herself might not belong in this cool blue silence, in the comforting glow of irrelevant drama, she with her visions of the dead and beats of wrong music clawing at her from the barrels of recoilless rifles; but almost immediately she turns and limps onward, grimacing from the pain in her back and in her cut foot. The accordion feels three times heavier than when she first picked it up. Her body lusts to ditch it, but she has an uneasy feeling that she is on a one-way trek and there will be no time to come back. And she cannot lose the Fourneaux-Dallapé, not when so much else is tentative or on its way out. Now, apart from Dolores and, God help her, even Jorge, the accordion is all she has left for a reference point.

She finds a flight of stairs, going down. The stairs are lit only by a votive pietà nailed in a niche. The wounds of the Christ are melodramatic and bloody. From the level below, women's voices arrange themselves in straight melodic lines out of the dampness and dark. Soledad recognizes the tune they are singing: It's a telenovela theme arranged in Gregorian form. The chant swells as she passes Byzantine archways to her right. Tapers have been placed behind the indigo stained glass lining this hidden chapel where nuns and patients together sing "Pain in the Afternoon." Beyond the chapel lies a row of cells, some lit by tapers, but all empty of human sound.

The clear voices fade behind her.

The ground under her feet moves. It lowers a few centimeters, then rises back to trip her up.

Immediately afterward comes a bubble of pressure, muffled by the ten thousand tons of stone the convent is built of. Someone screams briefly a long way away. The plain chant has stopped. Dust powders Soledad where she lies across the accordion case. She picks herself up, and once more hoists the Fourneaux-Dallapé. It takes all the strength she is capable of. Her heart is banging loudly; somehow the now-total darkness amplifies it like a bombo-skin. The blue reflection of chapel behind her is gone. She starts to run, ignoring the hurt in her foot, scraping the texture of wall with her left hand for guidance. The corridor twists left, or maybe joins another hallway. She tastes something raw, familiar in the back of her throat. Faint light grains out of the black oblivion, allowing her to make out another downward flight of stairs. She needs to go up but she descends anyway, under the low arches of the tunnel, because reflected against the floor at the stairs' base is a much stronger light and a white and growing noise that does not belong at all in this cool, shadowed place. The light wavers, flickers, as if beckoning her.

Her lungs twist. Still coughing, she rounds a corner deep in drifted dust and there it is, what she flees, what she seeks: fire. Fire the color of blood and lions--thus RDX from the four-inch recoilless maybe, or from air-ground rockets. Fire raging in a hundred dancers of light and color with their five thousand servants of smoke. And the noise is now total and clear, it is helicopter and mortars yes of course, it is the music fire makes, sure, the laughing cracking cold saraband of flame, but it is more also. Behind it the patterns of howitzers, the patterns of jets and attack choppers have locked in fully, she understands them now and it is cuto, the 68 rhythm of "Si mou estoma," the rhythm of Jorge's song. But the beat is unvaried where it should be loose, and broken in false places; so that now it is no longer Jorge's but his song, the man of the incomplete seventh, the Yanqui with no face. And she understands the fullness of their plans, in attacking the very rhythm of the cruce. And she knows beyond the shadow of a doubt that there is no escape. For Dolores will be found, and Jorge will be found, and when they catch Soledad they will--

Copyright © 2000 by George Foy

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details