Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

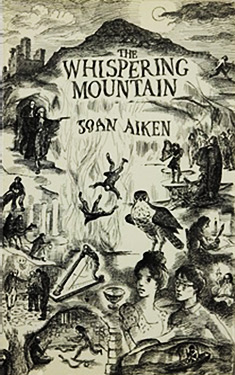

The Whispering Mountain

| Author: | Joan Aiken |

| Publisher: |

Jonathan Cape, 1968 |

| Series: | Wolves Chronicles |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In the small town of Pennygaff, where Owen has been sent to live after his mother's death, a legendary golden harp has been found. Knowing of the prophesy of the Harp of Teirtu, Owen must prevent the magic harp from falling into the evil clutches of its reputed owner, the sinister and diabolical Lord Mayln. But it won't be easy. Owen and his friend Arabis are plunged into a hair-raising adventure of intrigue, kidnapping, exotic underground worlds, savage beasts... even murder.

For only too late will Owen learn that Lord Mayln will stop at nothing to have the golden harp.

Excerpt

The Whispering Mountain

1

On a sharp autumn evening a boy stood waiting inside the high stone pillars which flanked the gateway of the Jones Academy for the Sons of Gentlemen and Respectable Tradesmen in the small town of Pennygaff.

School had finished for the day some time since, and all the other scholars had gladly streamed away into the windy dusk, but still the boy hesitated, shivering with cold and indecision. Once or twice he edged close against one of the soot-blackened pillars, so that his form was almost invisible, and, leaning forward, peered out through the close-set iron railings.

The street outside seemed empty. But was it really so? Very little daylight now remained. A thin yellow strip of light in the west made the shadows along the narrow cobbled way even blacker; there were too many doorways, porches, passages, and flights of steps in or behind which any number of enemies could lurk unseen. And a great bank of purple-black cloud was advancing steadily westwardacross the sky, blotting out what little light yet lingered. In a minute, torrents of rain would fall.

The sound of quick footsteps behind him rang in the paved yard and the boy swung round sharply, but it was only the schoolmaster, Mr. Price, on his way home to tea.

"Owen Hughes!" the teacher said with displeasure. "What are you doing here? Run along, boy, run along; you should not be loitering in the grounds after school has ended. Where are your books? And why have you no coat? It will rain directly. Your good grandfather will be wondering where you have got to. Hurry along now."

Mr. Price said all this as he passed the boy at a rapid pace, without pausing, meanwhile buttoning his own greatcoat against the huge drops of rain which were beginning to strike heavily on the flagged pavement. Owen's "Yes, sir," followed him, but he did not turn his head to see whether he had been obeyed, and Owen did not move from his position by the gate despite the downpour, which, now commencing in good earnest, soon drenched his thin nankeen jacket.

Intent on his scrutiny of the empty street, Owen did not even notice that he had begun to shiver with wet and cold, and that the scrap of paper which he rolled between his fingers had become sodden and indecipherable. Its short message was printed on his memory.

WE SHALL BE WAITING FOR YOU AFTER SCHOOL

The message, written in large, uneven capitals, was unsigned, but Owen was in no doubt as to where it had comefrom: only one of his seven persecutors could write.

"Dove Thurbey," he said to himself. "Dove Thurbey, Dick Abrystowe, Luggins Cadwallader, Mog Glendower, Follentine Hylles, Soth Gard, and Hwfa Morgan. They'll all be waiting, and they'll have stones and stakes and broken bottles. What had I better do?"

He simply did not know.

He could probably run faster than any of the seven, but he could not escape from a hail of cobblestones, and his chief dread was that his spectacles should be broken, for he possessed only one pair, and there was no means of repairing them. He was not a coward but he knew, too, that once Dove, Dick, Luggins, Mog, Follentine, Soth and Hwfa had him down there would be little hope for him. They wore metal-tipped clogs and they were all twice his size--Hwfa was nearly six foot--and big and brawny. Mog was going to work next month, Dick, Dove, and Luggins played in the town football team. The seven of them sat together at the back of the school and paid no heed to Mr. Price, who had long ago given up trying to teach them.

Nor was there much chance of aid. The citizens of Pennygaff were all snug in their kitchens by now, with doors and windows shut; if they heard a sound of fighting they were more likely to pull the curtains tighter than to leave their firesides in defence of an outsider. Wild boars from the forest were known to come into the streets after dark, and wild men too, on occasion; it was very seldom that the townspeople left their homes after nightfall except in compact groups.

While he was thinking these gloomy thoughts Owen heard, with surprise, the sound of running footsteps. Hisheart jolted with anxiety, hope, suspense. Could the runner be a possible ally? He could tell that it was not one of his enemies--the steps were too light and much too fast.

A man came into view, bolting at top speed down the mountain road. As he approached Owen saw, first, that he wore some sort of livery; next, that he was a stranger. He grasped a staff in his right hand. But here was no ally, Owen realized with sinking hope--this man was in the last extremity of haste and exhaustion. His legs would hardly have carried him had not the way lain downhill. As it was, they fled weakly along and he followed them, only half aware, it seemed, of where they were taking him.

As he neared Owen, words fell from him in a clot:

"SisplacePennygaff?"

"Yes!" Owen called back. "--Sir!"

But already the runner was past, careering down the hill into the darkness below, as if all the wolves of the Black Mountains were at his heels.

Down in the valley the town clock tolled six times.

Owen knew that in the next few moments he must come to a decision.

He had left his schoolbooks and coat under a loose board in the classroom--a hiding-place which, fortunately, had so far gone undiscovered. A coat would only hinder flight and give his pursuers something to catch hold of, while the books belonged to his grandfather and were precious with age and use. Owen could hardly imagine what his punishment would be if any harm came to them. Besides, he loved books for their own sake, and hated the thought of their being torn apart and dashed on the muddy cobbles.

What was that sound?

He turned quickly, just in time to see a black shadow dart from one point of concealment to another. He caught a whisper, and a brutal chuckle.

They were closing in.

There was no second way out of the school, which stood enclosed by iron railings, higher up the mountain than any other building on that side of Pennygaff. To reach home, Owen was obliged to descend the steep winding hill through the town, cross the single bridge over the river Gaff, and climb an equally steep hill on the other side. Even supposing he could outdistance his enemies as far as the bridge, he could hardly keep ahead of them up the farther hill; some of them would almost certainly be posted on the bridge, waiting for him.

Now a second figure dashed across the road, apelike and crouching; he recognized Mog. And to his left Owen heard the sound of a throat being cleared, deliberately, mocking and shrill; that was Hwfa, who, despite his size, still sang treble in the chapel choir.

"Well now, boys," whispered another voice--that was Luggins--"if the snivelling little dummer won't come out, go in and get him we must!"

Searching his pockets for anything that might serve as a weapon, Owen found a small heavy worsted bag. He ran his fingers over it in bewilderment; what could it be? Then he recollected that his grandfather had bidden him go during his dinner hour and collect a couple of items that had been omitted from the weekly order sent up by old Mrs. Evans the grocery. Soap and something else--perhapswhatever it was would serve to delay his attackers for a moment--

Just then both parties were checked by a new sound, the clipclop of hoofs and carriage wheels rattling over the uneven roadway. Next moment a chaise came briskly round the corner above the school and drew to a halt beside the gates, its single lamp shining on Owen's face.

"Hey, you--you there, you boy!" The driver's voice startled Owen by its loud, harsh, resonant tones. A tall man, swathed in many capes, waved a whip at him commandingly. The deep brim of his beaver hat shaded his face from Owen's view.

"Y-yes, sir," he stammered. "Can I help you?"

"Is this dismal place the town of Pennygaff?"

"Yes, sir."

"Thank God for that, at least. I've been traversing these hideous black hills for the best part of three hours--I wish to heaven I may never have to set foot here again! Well then, can you direct me to the museum--though, by Beelzebub, if ever there was a piece of arrant impudence, it is for a pre-historic settlement like this to possess such a thing? Place should be on show itself as a savage relic."

"Down the hill, sir, across the bridge, and up the other side. You'll see it on your right, above the Habakkuk chapel," said Owen, rather indignant at this slight on the town of his ancestors, and surprised, too. What could this stranger want with the museum, at such an hour?

"Any decent inns here?" the man demanded.

"There's one inn, sir--the Dragon of Gwaun, by the bridge."

"One--is that all? How far is this desolate spot from Caer Malyn?"

"A matter of twenty mile, sir."

"Perdition! The mare'll never do it, she's dead lame. I fear I must resign myself to pass the night at the inn." The driver was about to touch up his horses when he paused again, and said in a careless, offhand manner,

"Do you know, boy, if a pair of ruffianly rogues of English peddlers have come to this hamlet recently--a tall man and a short one? Bilk and Prigman, I believe they call themselves."

"Why--why, yes, sir," Owen said, pondering, "I do believe such a pair has been about. You might hear tell of them at the inn."

"Humph! Very probably! Come up, then, mare!"

The chaise clattered on without a word of thanks from its driver, leaving Owen ready to curse himself for his folly at letting slip such a chance of escape. Why had he not offered to accompany the man and show him the way to the museum? Nothing could have been more natural. But there had been something about the stranger's harsh voice and cold, half-angry bearing that made Owen discard the notion as soon as it entered his head; this was not a man likely to grant favours.

Almost before the sound of hoofs had faded down the hill, Owen's attackers were closing in once more. Only three of them, though. It seemed that he had guessed right; Soth, Dick, Follentine, and Dove were waiting down at the bridge to cut off his escape.

Well, he would sell his life dear.

He pulled the cloth bag from his pocket and, delving inside, extracted a twist of paper.

"Go on, Hwfa, man! Pound the little flamer!" whispered Mog.

As the three of them edged towards him Owen, suddenly taking the initiative, darted forward and shot the contents of the packet full into Hwfa's face.

It was snuff. Nothing could have been more unexpected, or more successful. Stopping short with a gasp of pain, Hwfa rubbed and rubbed at his eyes, cursing and blubbering.

"Wait till I get at you, will you! Oh dammo, my eyes. Have the head off him, Mog!"

But Owen had not waited. Darting past Hwfa he doubled round Luggins and Mog while they were still taken by surprise, and was off like lightning down the hill. In a moment, though, he heard them coming after him. A cobblestone whistled past his ears. He had very little start.

Halfway down, the road from Hereford came in on the left. As he crossed the turning, Owen was obliged to swerve in order to avoid a hooded wagon which swung out of the side road and turned downhill towards the bridge. Grabbing, to steady himself, at the shaft, which had passed within six inches of his shoulder, Owen glanced up at the driver in apology.

"I'm sorry, sir," he panted, and then, in utter astonishment, "Why--Mr. Dando!"

"Eh? What's that? Who? Where?" The man on the box peered down at him absently. "Dando's my name sure enough, but do I know you? Face seems familiar, certainly--but then, so many faces do--all faces much alike,I am thinking? Still, yours--yes, seen it before somewhere, I do feel I have. But where, now?"

"Don't you remember? You took me up in the port of Southampton last summer when I was starting out to walk to Wales and carried me as far as Gloucester--surely you recall?"

Mr. Dando was still rubbing a hand through his long dark locks, making them stand on end, while he muttered, "Perhaps--perhaps--" when he was interrupted by the three pursuers, who arrived with a clatter of clogs and hurled themselves on Owen. For a moment, all was confusion. Owen fought desperately, but his feet were knocked from under him and he was being borne to the ground when a girl in a red dress put her head out at the back of the wagon.

"What is it, Father? What is happening? Why--Owen!"

Big clumsy Mog, hindered temporarily from his assault by the bodies of his two allies, looked up at the girl on the wagon and gaped in astonishment at what he saw. Her dark hair was piled on top of her head in a knob, or coronet, and perched upon this, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, was a large black-and-white bird, with a curved roman bill.

When the girl saw what was happening she exclaimed, "Scatter them, Hawc!" in a voice that carried like a bell.

Instantly the great bird launched himself off her head, rose, circled a couple of times high over the combatants, and then hurtled down on them in a whistling dive. He landed with a thump, striking his razor-sharp talons into the jacket of Hwfa, who gave a shrill yell and ran for his life. The falcon loosed him, at another command from thegirl, and returned to pounce on Luggins, scoring a set of deep parallel tracks through his tow-coloured hair. Completely terrified at this unexpected pain and the fierce clutching weight on his head, Luggins let go of Owen, whom he was slowly throttling, and tried to shake off the falcon. Mog, seeing the battle was lost, had already made his escape.

Luggins stumbled after him, calling out desperately,

"Mog! Mog! Don't leave me! Get this brute off me, boy!

Mog made not the slightest effort to help, but at another whistle from his mistress Hawc released the punishing grip on Luggins's scalp and came oaring back through the rainy night, to take up his perch once more on the girl's crown of hair.

She had jumped off the wagon and was hugging Owen, who could hardly believe his eyes.

"Arabis! What are you and your father doing in these parts?"

"Owen, are you all right?"

"Yes, they had hardly started on me--thanks to Hawc!" He settled his glasses--which were dangling from one ear but miraculously unbroken--back on his nose. "But how do you come to be here?"

"I asked Dada to come through by Pennygaff on purpose so that there would be a chance of seeing you, maybe. On our way to the fair at Devil's Leap--Nant Agerddau, we are. But how is it with you, Owen bach? Dear to goodness, how you've grown! Taller than me, now! Did you find your grandfather all right? Are you happy, with you? Who were those brutes?"

"Boys from my school."

"Fine sort of school! Why were they after you?"

"Oh, just because I am a stranger here."

Owen glanced down the hill. His enemies had dispersed. For the moment, at least, he was saved.

"There's silly, and your father and granda born here. Gracious, how it rains! Come inside the wagon, Galahad won't mind another in the load, will he, Dada? I'm sure Owen doesn't weigh any more than he did last summer--thin as a withy he is, still."

"Galahad? He could haul half the mountain and never notice. Fresh as a daisy, aren't you, my little one?" Mr. Dando clucked to the horse--who was indeed of massive build--and shook up the reins; the wagon began to rumble slowly on down the cobbled hill while Arabis and Owen scrambled up the steps, under a bilingual notice which said, "Barbwr a Moddion. Barber & Medicine. Prydydd. Poet."

Once inside, Owen looked round with indescribable pleasure at the place which had been his happy home for two months as they travelled leisurely across southern England. And a snug, delightful home it made: the roof and sides were cunningly woven of latticed withies, which had a canvas facing within and without; a coat of pitch had rendered this weather-proof on the outside: inside it was whitewashed and Arabis, who had a decided talent for painting, had decorated it with a design of roses, cabbages, and daffodils. Red drugget covered the floor, and a fire burned in an iron stove. An aromatic smell came from the many bunches of herbs which hung overhead drying in the warmth, and on a high shelf stood pillboxes, medicine bottles, jars of ointment and papers of powder. Two shelf-bedswere neatly made up and covered by patchwork quilts, while two more, strewn with cushions, were used as seats. A red baize curtain could divide the room in half but was at this moment drawn back. A table, fastened to the floor, had a kind of wicker fence to prevent dishes sliding off it if the wagon tilted. An oil lamp swung on a chain from the ceiling, throwing warm golden light and a never-ending procession of shadows. Pots, pans and some Bristol ware shone on a slatted shelf: everything there sparkled with cleanliness. From a hook on the wall dangled a gaily ribboned instrument, something between a violin and a mandolin; it was called a crwth.

"I'm glad you still have Hawc," Owen said, as the falcon, excited and roused from his foray, continued to hiss and heckle, raising and lowering his wings.

"Yes, indeed!" Arabis slipped a hood over Hawc's head to quiet him, and placed him on a perch ingeniously contrived from an old broom. "If we hadn't, hard it would be indeed to keep the stockpot filled; Dada is writing a long poem about King Arthur now, just, and there is absentminded it makes him! he only speaks on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Sundays at present, so lucky you are that today is Wednesday."

She laughed, nodding towards a great heap of books and sheets of paper scrawled across and across with handwriting, which covered one of the beds. Owen, screwing his head round, read a title on the sheet nearest him: "The King at Caerleon: An Epic Poem in CCC Cantos by Tom Dando. Canto CCLXXXVIII."

"I still think it must be odd to have a father who speaks only every other day," he remarked involuntarily.

"Oh well--" Arabis was philosophical. "Not so bad, he is, old Tom. Better it is than having no father at all." Then she blushed and exclaimed anxiously, "There's sorry I am, Owen dear! Where were the wits in me? Have you any news of your father yet?"

He shook his head. "No. But that means little. Grandfather thinks he may still be alive; a prisoner, perhaps, in the Chinese wars, or cut off somewhere so that he cannot send a letter. And letters take so long to come."

"Tell me about your granda, then, is it? Found him all right, did you, after we parted that day at Gloucester?"

"Yes," Owen said, remembering the sad day last summer when he had been obliged to say goodbye to the kind friends who had carried him so far. "Yes, I had a lift in a carrier's cart along to Monmouth, and from there I walked; it took a week but I was lucky with the weather."

"And your granda? Was he pleased to see you? Fond of him, are you?"

Owen had to look away from Arabis. There was too much of a contrast between the warmth of her voice, the kindness in her dark eyes, between the whole friendly comfort of the little home on wheels and the other home he was so soon to re-enter. He stared hard at the falcon, biting his lip. After a moment he was able to say,

"It took a little time for Grandfather to--to believe that I was his grandson."

"But you had the papers--the certificate of your birth, and your father's letter?"

"He said anybody might have stolen them--that my having them proved nothing."

"There's silly! Who'd do such a thing, pray? And so?"

"Well, so in the end he took me in. He still says, though, that--that I must take after my mother's family, that I'm not like a Hughes. But he's a just man. He--he said he was prepared to give me a home and pay for my education."

"So I should think indeed!" cried Arabis. "His only son's son! And your poor mama dead of typhus fever on the voyage home from China, and the captain's letter--There, there, never mind me, bach, I didn't mean to grieve you by reminding you. Here, have a mug of soup, is it?"

Owen smiled, remembering how Arabis always administered hot soup to anyone in trouble.

"Good soup it is too," she said, "Hawc caught a hare as we came over Midnight Hill. And I put in a drop of the mead a sailor gave Dada in Cardiff. So drink up."

Owen kept his eyes on Arabis over the rim of the mug. He had never for a moment forgotten her during the time spent at his grandfather's, but the picture of her had set firm in his mind and become less alive. Now it was almost a shock to see her again--her real self--talking and laughing. He found that he had grown so that he was very slightly the taller of the two.

"You haven't changed a bit, Arabis," he said.

She had long, soft hair, black as coaldust, which she wore in the knot on top for Hawc's benefit. Her eyes looked almost black too, because the pupils were so big, but they were really a very dark grey. Although she spent most of her days out of doors, scouring the hills and woods for medicinal plants while her father, with Galahad and the cart, plodded along the road, her skin never tanned, butremained pale and clear. When she smiled a three-cornered dimple appeared under her left cheekbone.

Owen and she were not unalike, both being thin and dark, but his eyes, behind the glasses, were brown, not grey. On the journey from Southampton to Gloucester people had sometimes taken them for brother and sister. Owen knew that Arabis had once had a younger brother but he and her mother had both died of an inflammation in the hard winter ten years before.

"So you go to school now?" Arabis said. "Lucky boy! You can learn history and astronomy and all the languages that they speak in foreign lands. It makes me sad to think that if I met my mother now she might be speaking and maybe I'd not understand her."

"You'd pick it up fast enough," Owen said, remembering Arabis had told him her mother came from the island of Melita. "You are such a clever girl, Arabis! I believe you know all there is to know about herbs and wild creatures--and younger than me, too!"

"There's wonderful!" she laughed at him. "How would I help it? But to learn in school! I'd go, if it didn't mean leaving Tom. Don't you love learning?"

"Yes," Owen said truly. He did not speak again of his difficulties with Mog and the others who hated him because he was a stranger. Why whine about his troubles to Arabis? Nothing seemed to perturb her; he had seen her quiet and unafraid before a bullying magistrate, accused of witchcraft; and equally calm, facing the charge of an angry bull, maddened by the pain of a broken horn. She would probably think he was making a fuss over a trifle.

But, he suddenly thought, he could tell her about hisother worry. Arabis was the only person he could think of who might have sensible advice to offer.

"Arabis," he said on this impulse, "have you ever heard of the Harp of Teirtu?"

"Telyn Teirtu? Indeed yes. Tom would be telling us stories about it when we were little: that it was made of gold, and had three rows of strings, one for men, and one for kings, and a row that would burst out playing all on its own if a strange hand tried to steal the harp; and a lot more beside."

"Yes, that is it," he said. "My father told me the story too. Kilhwch, son of Prince Kelyddon, got his cousin King Arthur to help him steal it for a bride-gift for the Princess Olwen. It was taken from Castell Teirtud to the king's castle at Caerleon, and then to the castle of Yspaddaden Penkawr. But then it was lost, some say St. Dunstan had it and gave it to St. Ennodawg, some that it found its own way home to Castell Teirtud."

"There was a prophecy about it made by one of the old bards," Arabis said.

"When the Whispering Mountain shall scream aloud And the castle of Malyn ride on a cloud, Then Malyn's lord shall have and hold The lost that is found, the harp of gold. Then Fig-hat Ben shall wear a shroud, Then shall the despoiler, that was so proud, Plunge headlong down from the Devil's Leap; Then shall the Children from darkness creep, And the men of the glen avoid disaster, And the Harp of Teirtu find her master."

"But it is a very confusing prophecy, indeed, for how could the castle of Malyn ride on a cloud? And who is the despoiler? Anyway, what about the harp, boy?"

"Well, that's it," Owen said. "My grandfather thinks he has found it."

"No!" said Arabis, and her eyes went wide. "Well, there is a piece of news, indeed! But you look as glum as if you had lost a guinea and found a groat. Where did he pick up the old harp?"

"He was taking stones from the ruined monastery on the island in the river Gaff, to build another room on to the museum. He pulled down a bit of wall and found a little closet hollowed out in it. In the closet was an old chest lined with copper, and in the chest was the harp."

"No nonsense?" said Arabis, much interested. "Will it play?" She glanced up at the crwth hanging on the wall. "Dearly would I like to get my fingers on it!

"No, it won't play. It is old and black and all the strings but one have gone. But the frame is made of gold, Grandfather thinks, and there is ancient writing on it."

"Valuable, then, it will be?"

"Yes," said Owen gloomily, "and that is one of the reasons why there is trouble in the town."

"Why, in the name of ffiloreg?"

"Nobody can agree about what should be done with the harp. Some say, sell it, and let the money go to build a new school. There's a foreign Ottoman gentleman in the town, and it's believed he wants to buy it. But some say the harp should stay here because it was found on town land and belongs to the people of Pennygaff. And everybody seems to be angry with Grandfather."

"What does your granda say?"

Owen looked troubled. "He says it isn't clear yet who has a right to the harp. He says the island where it was found isn't town land."

"Whose is it, then?"

"Grandfather thinks it probably belongs to the Marquess of Malyn. He owns most of the land round here."

"Ach y fi! That bad man!"

"Is he so bad?"

"When my mam was ill," Arabis said, "we'd halted the wagon in a patch of bushes up by the lodge of Castle Malyn. The lodgekeeper's wife, who was a decent sort of woman, had Mama in her cottage, with my little brother, and was nursing them. His lordship got word of it and said he'd have no gypsies and vagabonds squatting in his cottage, or tinker' wagons standing by his park gates. My dada asked to see him and told him she was ill, and it was only for a little time, till she took a turn for the better. But the lord said if she was ill she had better go to the workhouse, rather than infect his people. So he sent three of his men to carry her out of the lodge. Out in the snow they carried her, and put her in the cart. So we went on, over the hills, but that night was the worst storm of the winter, and the horse died in the shafts, halfway over, and Mama and my little brother died too."

There was silence for a minute. Then Arabis went on,

"I've heard other tales of him too. They say the rents he charges his tenants are the highest in the country, and if they can't pay, out they go that same day. And that he treats his servants like slaves--hundreds of them are at work, day and night, polishing the hoofs of his horses,blowing between the leaves of his books, cleaning his collection of gold things. He keeps a footman who must run before his carriage wherever he drives. Imagine having to run faster than a carriage all day long!"

With a start, Owen remembered the man who had rushed panting down the hill. So many things had happened since then that, until this moment, the strange event had vanished from his mind.

Arabis went on, "If the Harp of Teirtu really belongs to him, it could hardly have a worse owner."

"Nobody knows for sure yet," Owen said. "But Grandfather is determined to act fairly in the matter."

Looking out (while they talked the horse Galahad had been slowly but stoutly breasting the steep hill from the river Gaff) he added, "We are almost at my home now. I should so much like Grandfather to meet you--won't you please come in and--and take some refreshment? I think--I'm sure he'd like you."

As he said the words he felt a faint qualm. But surely old Mr. Hughes would like Arabis and her father? Who could fail to do so?

"My word!" Arabis exclaimed, looking out. "Do you live in a museum, then, boy?"

"Why yes," he said, "my grandfather is the curator, you see, ever since he retired from being a sea-captain like my father."

The little town now lay below them, slate roofs shining with rain in the gloom, and only a dim street lamp here and there to throw a few dismal patches of light. In front of them a pair of gates, not unlike the school ones, led to a cobbled yard. A notice on the gates bore the words

"YR AMGUEDDFA."

"O Dewi Sant!" breathed Arabis enviously. "To live in a museum! There's lucky! Whenever we stop in a town, if Tom is busy with the hair-cutting, I always look for the museum. Full of wonders, they are. And your granda is the ceidwad? He must be a wise man, Owen, and greatly respected in the town!"

"Well," Owen said, "yes." A troubled frown creased his brow. "But this trouble of the harp, and the sleepers' tickets--'

"Sleepers' tickets?"

"Here we are, though," he said. "I'll tell you about that later. You can stay the night here? The wagon will go in the courtyard."

"Hey, Da!" Arabis jumped out and ran round to take the reins from Tom Dando, who was in his usual dream and would have driven on over the mountain westwards towards the coast. She turned the horse and led him in through the gateway. "Wake up, Dada! Owen lives here in the museum, lucky boy! And he's invited us in to meet his grandfather. Where shall I tie Galahad, Owen? To this stone pineapple on the gatepost?"

She kicked a loose rock under the rear wheel of the wagon so that it should not run away backwards downhill into the river Gaff.

The museum was housed in a brick hall that had once belonged to the Detached Baptists, until they had merged with the Separated Rogationists, who owned a larger chapel, built of granite, with an organ. The courtyard in front of the hall was a pool of dark, split by feeble raysfrom a small lamp over the door. Here another notice, fresh-painted, announced that the museum was open from 10 am to 5 pm every day except for the Sabbath, St. David's Day, St. Ennodawg's Day, Christmas, Easter, and various other public holidays. It was signed O. Hughes, Custodian. The light above was just bright enough also to reveal some words chalked on the wall under the sign. They said:

GIVE US BACK OUR SABBATH OPENING! DOWN WITH SLEEPERS' TICKETS!

Looking desperately worried, Owen began wiping this message off the wall with his handkerchief, while Arabis exhorted her father,

"Come you now, Tom! Don't you want to meet Owen's Granda?"

"Oh, well, now, I don't know," Mr. Dando said doubtfully, struggling out of his dream. "Meet his grandfather? What for? Do we really want to do that? Eh? More to the purpose, does he want to meet us?"

"Of course!" Arabis gave him an impatient shake and pulled him down, straightening his cloak and putting him to rights. Dislodged from his box he was revealed as an unusually tall, thin man, with wild dark locks beginning to turn grey, and deep-set eyes in a long, vague, preoccupied face.

Owen by this time had opened the heavy outer doors of the museum and stepped into a large porch. Here he found another damp sheet of paper lying on the floor which,when he held it towards the light, proved to bear the message:

LEAVE THIS TOWN, OWEN HUGHES, WE DON'T WANT YOU

Without a word he folded it small and thrust it into his jacket pocket. Arabis and her father, who came up at this moment, had noticed nothing. Owen pulled on a bell-rope, which hung by the locked inner door, and they all waited, shivering in the damp darkness.

Owen's qualm was growing inside him faster than a thundercloud. How would his grandfather receive the visitors?

He was to discover soon enough.

The inner door flew open as if it had been jerked by a wire. His grandfather stood just inside, peering angrily out into the gloom.

"Is that you, boy?" he said sharply. "You are over an hour late from school. What kept you, pray? You knew that I particularly required you to be on time today. I will not have such unpunctuality--I have told you before!"

"I--I am sorry," Owen stammered, "but, you see--'

"Call me sir, or Grandfather! Well! What explanation have you to offer? I suppose you have been idling and playing and wasting time with your classmates."

Captain Owen Hughes--or Mr. Hughes, as he preferred to be called, saying there was no sense in using bygone titles--was a smallish, spare, dried-up old gentleman with pepper-and-salt grey hair, worn in a short peruke and tied with a black velvet bow. He had on a jacket and pantaloonsof grey alpaca, exceedingly neat, but shabby. His linen, however, was white as frost, and the buckles on his old-fashioned shoes and his eyes behind his rimless pincenez were needle-bright.

"Sir, I m-met the kind friends who carried me all the way to Gloucester last summer. I have brought them to see you--" Owen began again.

"Friends!" exclaimed his grandfather harshly. "I thought you said they were a travelling tinker, or bonesetter, and his gypsy daughter? How can such lower-deck sort of folk be friends?"

"Grandfather--please!" Owen was in agony. "You must not speak of them so! Here they are, Mr. Dando and Arabis--'

"Tush, boy, I have no time for them now, or ever. I have an important appointment at the inn and must delay no longer. But I can tell you this: when I return you shall be punished for your tardiness--soundly punished." He shook himself impatiently into a frieze greatcoat and picked up a shovel-hat and cane, muttering, "Arabis, forsooth! What kind of an unchristian name is that?"

"But sir, they are here now, in the porch!"

"Then they will just have to take themselves off again--I've no intention of receiving them." Mr. Hughes cast an angry glance at the cloaked figures of Mr. Dando and Arabis standing quietly in the shadows. "Bustle along now--make haste, pray!" he snapped at them. "I must go out, and I've no wish to leave the museum while there are strangers loitering outside it. Let me see you take your cart out of the yard, if you please!"

"Certainly, sir," Tom Dando replied with dignity. "Wehave not the least wish to remain where our presence causes inconvenience."

Owen, half choked with grief and indignation, could say nothing. He stood speechless while Arabis turned the horse and led him out of the gate. Her father climbed back to his perch on the box. Then, realizing that unless he moved they would depart without another word, Owen flew after them and caught Arabis by the hand.

"Arabis, I am sorry, oh, I am sorry!"

Her grave face broke into the smile with the three-cornered dimple.

"Proper old tartar your granda, isn't he?" she whispered. "Poor Owen, there's sorry I am that we came to bring trouble on you. Never mind, boy, we'll take ourselves off quick."

"I wish I were going with you. I hate him!"

"There's silly! When he's giving you a home, and a fine education too? You make the most of it, boy!"

"But when shall I see you and Mr. Dando again?" he said forlornly.

"Does he ever let you out for a bit of pleasuring? We'll be stopping over by Devil's Leap for a week while the fair lasts--it's only half a day's ride. Would he let you go?"

"Not while I'm in such disgrace, for sure."

"Welladay!" she said laughing.

"Owen!" called his grandfather. "Come here directly!"

"Never mind," Arabis whispered. "We're sure to meet again." She gave his hand a hurried squeeze and jumped nimbly back into the wagon as it rolled away.

Dumb with suppressed feeling, Owen moved back towards his grandfather.

"Now sir, what have you to say for yourself?" barked Mr. Hughes. "Rogues and gypsies off the road, indeed! Never let such a thing occur again, I beg! And now, just now, too, when we are housing such a treasure in the museum. Thoughtless, reckless lad! I trust you did not speak of the Harp of Teirtu while you were hobnobbing with that shady pair?"

"I--yes, I did, Grandfather."

Mr. Hughes raised his hands to heaven. "May all the saints give me patience! Why was I ever saddled with such a millstone round my neck? And now I must go off to see his grace and leave you--you--alone in charge of the harp! I've a good mind to take it with me, inclement though the weather be. But no," he added, half to himself, "in the circumstances that would hardly be wise, until it is certain how matters stand. However, let me be sure that all doors and windows are double-locked, barred, and chained. I have enough to contend with, dear knows, in this town of cockatrices, without risking the loss of my good name. Boy! follow me."

In sullen silence Owen accompanied his grandfather as they made the rounds of the windows and the front and back doors. All were securely fastened.

"Very well," Mr. Hughes said at last. "Now--while I am gone, unbar to no one--no one at all, do you understand me, boy? No respectable person should be abroad at this hour, in any case. If there should be a knock, open the slot in the outer door, ask the business of whomever it be, and tell them to return in the morning. Do you understand?"

"Yes, sir."

"And don't show me that sulky face! While I am gone you may occupy yourself usefully by dusting the glass cases and polishing the Roman, Saxon, and Danish weapons. You will find your supper in a bowl. Do not neglect to stoke the brazier. There will be no occasion for you to enter the library--I do not wish to come back and find you with your nose in a book and no work done! Do not retire to bed until I return--I shall not be late."

"No, sir."

"No, sir, yes, sir!" snapped his grandfather. "I would wish to have less of your yes, sir, and a more obliging, open manner and honest will to please. But it is no matter. We cannot, I suppose, fabricate a silk purse out of a sow's ear.--I will take my departure, then. Let me hear you make fast the front door behind me. I have the key of the rear."

He stepped out into the night and Owen shot home the heavy bolts.

When his grandfather's brisk footsteps had died away across the yard, Owen picked up a feather duster and began listlessly passing it over the glass cases which held Roman pottery, geological specimens, birds' eggs, and old coins. These, with a stuffed sheep, a crossbow, and some iron tools, use unknown but probably instruments of torture, occupied the two main rooms. The library, a smaller room, shelved from floor to ceiling, housed volumes of sermons and reference books. A sign on its door said: "Sleepers' Tickets 5/--. Not transferable. No sleeping in the Library without a Ticket."

At the rear of the museum a series of small offices had been adapted by Owen's grandfather, with the minimum of alteration, to serve as kitchen, washroom, and broomcloset. Owen slept in the broom closet, his grandfather in the main hall on a truckle bed, erected at night beside the helmet of Owen Glendower, which, up till now, had been their most valuable exhibit.

The place was bleak and cheerless enough, its sole source of warmth being the small charcoal brazier which served Owen and his grandfather as a cooking-stove. Some rush dips gave a flickering uncertain light and threw odd-shaped shadows.

In general Owen did not object to being left alone at night in the museum--his grandfather's occasional absences on town business gave him indeed a welcome sense of freedom--but this evening he felt a strange anxiety and uneasiness. He tried to tell himself that this was merely because of the encounter with Hwfa's gang, or the second unhappy parting from Arabis and her father. But there was something more to it than that.

Taking a rush dip he once again made the rounds of all doors and windows listening at each. But there was nothing to be heard save the moaning of the gale outside, as it swept over the bare grassy mountain and licked round the corners of the museum. The wind itself did not penetrate, but the stout little building quivered with each new blast, so that the air inside was agiatated and the candle flames were never steady.

Having satisfied himself that all was secure, Owen wandered back to the kitchen, where his supper, a bowl of flummery--cold, sour, jellied oatmeal--was set out for him. He had no appetite for it, and covered it with a dish, to wait for breakfast. His heart ached at the thought of Arabis and her father, out on the windy mountainside.Would Galahad still be plodding on his way towards Devil's Leap, or would they have decided to stop and camp somewhere for the night? He imagined them, snug by their stove, Galahad, good easy horse, turned out to grass, a blanket which Arabis had embroidered with his name, Gwalchafed, strapped round his barrel sides. Tom and Arabis would be telling stories--since it was one of Tom's talking days--or playing verse games, swapping rhymes. Or they would be singing together, treble and tenor, accompanied by Arabis on the crwth, hymns, probably, for Tom dearly loved a good hymn. Many a time had Owen heard him booming out the strains of "Llanfair," or "Hyfrydol," or some other favourite, conducting himself so vigorously that he swayed about like a tree in a hurricane, and seemed likely to lift himself clean off the ground.

Plucking his thoughts away from this picture, which presented such a contrast to the chill, silent museum, Owen busied himself with stoking the brazier and polishing the weapons. But his thoughts would not be checked; they raced away from him like a pack of hounds, and their cry was that he would be happier anywhere else, working as a clerk, as a labourer, in the fields, in the mines, anywhere rather than this cheerless place, where he was barely tolerated by his grandfather, and treated as an interloper by the boys of Pennygaff.

Suddenly, almost without being aware of it, Owen found that he had come to a decision.

He would stay here no longer; he would go to Port Malyn and try to find employment on a ship.

He would have liked, above everything else in the world, to join Arabis and her father in their roving life, buthe was much too proud to run after them begging to be taken up. What could he offer them? Nothing. Of what use was he? None at all. He was unhandy, short-sighted, timid, and the only subject on which he could claim to be well-informed was navigation, since he had been born and brought up on His Majesty's sloop Thrush.

No, a ship was the only answer.

With neat dispatch, he packed his possessions in a bundle: two new shirts, some hose, a comb, a lock of his dead mother's hair, and his greatest treasure, a little book which had been given him by his father. It was called Arithmetic, Grammar, Botany & c; these Pleafing Sciences made Familiar to the Capacities of Youth. His other treasure, a compass, always hung round his neck on a cord.

It would be needful to leave a note for his grandfather: no easy task. Owen wasted five or six sheets of paper in false starts before achieving a message that satisfied him.

Dear Grandfather:

I feel I do not truely belong here & can only add to your Troubles. So I fhall not give you the Burden of my Prefence any longer, but fhall try to find Employment on a fhip fo as to follow my Father's Calling. I am forry to be obliged to carry fome of your Property with me [he meant the shirts] but will fend Money to Repay as foon as I am in a Pofition to do fo. That you may long continue to enjoy the blefsings of Health is my Sincere With. Pray reft afsured that I am very Senfible of the many Kindnefses you have fhewn me & though I feel I am undeferving of them I am & fhall always Remain

Your moft dutiful Grandfon

Now, where to leave the note so that his grandfather would be sure to discover it in due course, but not too soon? After some consideration Owen decided to put it under the Harp of Teirtu; his grandfather's first act in the morning was always to lift the cover off this treasure, but on his return late at night he was unlikely to do more than glance in and make sure that it was still in its place.

At this moment Owen was startled by a single loud bang on the front door. His heart shot into his mouth. Could Hwfa and the others, discovering that Mr. Hughes (whom the town boys disliked but held in considerable respect) was from home, have agreed that this would be a good time to raid the museum? Or could Arabis and her father have returned? No, sadly Owen dismissed that idea. Full of apprehension for his trust, he made his way to the porch, opened the peephole in the outer door, and looked out.

He found his face two inches from another--a broad, olive-coloured countenance with two splendid black moustachios and two enormous chestnut-coloured eyes.

"My dear sir, friend, mister," said this face, "I beg pardon exceedingly if I have disturbed your repose, but could I speak with the custodian, curator, guardian of your museum?"

"I am afraid the museum is shut," Owen said. He did not want, if he could help it, to disclose the fact that his grandfather was not there.

"Heigh-ho, alack, yes, I have already ascertained as much from your notice," agreed the visitor. "But the gentleman whom I wish to interrogate, catechize, moot, frisk, reconnoitre--Mr. Hughes--is he within?"

"He can't see you," Owen said stoutly, "He is engaged at present."

"O lud, lud! And will he never be at liberty, scot free, out of harness?"

"I do not think he will be free tonight, sir. May I take your name and make an appointment for you to see him tomorrow?"

"There would be no chance of a peep, just one glimpse, glance, espial, at all your beautiful treasures and antiquities while I am here?"

"Oh, not a chance at all, I am afraid, sir. Mr. Hughes is very strict about opening hours."

"Lackadaisy! Of this I have been apprised, advised, tipped the wink. In that case, as I would not wish to do anything obreptitious, please to tell him that the Seljuk of Rum will do himself the honour of waiting on Mr. Hughes tomorrow at ten precisely."

"The Seljuk of Rum?"

"If you please! And until then I will wish you the top of the night, my dear sir."

The black moustachios parted to reveal a brilliant flash of white teeth, the large face nodded (bringing into view a section of a high cap made of black, tightly curled fur) and then the visitor turned on his heel and was gone.

Owen, puzzled, anxious, and very much wondering if this mysterious caller had believed him when he said that Mr. Hughes was engaged, shut the peephole again and made his way back to the library.

The harp stood, for the present, on the big table in this room which, since Mr. Hughes's unwelcome introduction of sleepers' tickets, was little used. Regardless of hisgrandfather's prohibitions, Owen carefully removed the canvas cover from the harp and stood for a few moments admiring it. It was not the full-sized modern instrument, tall as a man, but a travelling harp, the sort used by Henry VIII, about two foot six inches high, which was intended to be balanced on the player's knee.

Owen, who loved mathematics, thought of it as a triangle which had been blown by the wind so that one side had bellied out and up, giving a line like that of a ship's prow. The maker had evidently seen this likeness, too, because the frame, which was richly carved with leaves and fruit, had a kind of figurehead at the top corner, staring up and ahead, away from the player. The metal of the frame was tarnished with age and dirt to a bronzed dark green, nearly black, and the snapped strings hung curled in fantastic twists and tendrils. But although the harp was dirty and broken, Owen thought it one of the most beautiful things he had ever seen, and he could not forbear passing his hand round the graceful flowing lines of the frame, and then plucking with the tip of his finger at the last remaining string. The sound it gave out was low but piercingly clear; it seemed to fill the whole room with echoes. Glancing nervously over his shoulder--but no one was there--Owen lifted the pillar of the harp and tucked his letter underneath so that one corner showed, then replaced the cover which protected the harp from dust and damp.

He had no intention of violating his trust by going off and leaving the museum unguarded; he meant to slip away as soon as Mr. Hughes had retired to bed. Meanwhile, as he was very weary, he crouched on the floor; he thought there would be less chance of his dropping off to sleep onthe ice-cold flags than if he sat on a chair. Reading was forbidden, so he recited to himself all the poems his mother had taught him.

When he had gone through all his stock he tried to recall the prophecy that Arabis had quoted that afternoon:

When the Whispering Mountain shall scream aloud And the Castle of Malyn ride on a cloud, Then Malyn's lord shall have and hold The ... something ... harp of gold ... ... Then shall the despoiler, that was so proud Fall headlong down from the Devil's Leap ...

What could the lines mean? The Whispering Mountain was another name for Fig-hat Ben, the mountain that lay between Pennygaff and the next town, Nant Agerddau. Owen knew that it was called whispering--y mynydd sibrwd--because inside the mountain, in the cave known as Devil's Leap, there was a hot spring which constantly gave off steam and made a bubbling, or whispering sound. In bygone days the place was thought to be haunted by ellyllion--ghosts who stretched long skinny arms out of the water and pulled you in--if not by Y bwci-bo, Old Horny himself. But now people went there to take the waters for their rheumatism, and the little town, Nant Agerddau, had sprung up in the rocky glen below the cave. But how could a mountain scream aloud? And who was the despoiler who would fall from the Devil's Leap? The Leap itself was a great gulf, boiling with steam, inside the cave, whose depths no man had ever dared to plumb. And the Castle of Malyn was of course at Port Malyn, on the coast,ten miles away. How could it ride on a cloud? Puzzling over these mysteries, Owen tried to remember the last lines. Something about the Harp of Teirtu ...

Then shall the Children from darkness creep (what children? what darkness?) and something or other about disaster?

And the Harp of Teirtu find her master.

It did sound as if the harp were in some way definitely connected with the Marquess of Malyn. Which was a pity, as by Arabis's account he certainly did not deserve to possess such a treasure.

Owen gave a deep unconscious sigh, that was half a yawn. His eyes closed. With a guilty start he forced them open and sat upright, but in a few minutes his head was nodding forward again.

"Arabis," he murmured, nine-tenths asleep. "Arabis ... no use waiting at ... Devil's Leap ..."

Then, gently and silently as sand falls in an hour-glass, he toppled sideways on to the floor and lay curled up, fast asleep, underneath the table. One slow tear trickled from his cheek to the dusty flagstone on which it was pillowed.

His slumber was so profound that he never heard the crunch of footsteps outside, nor the cautious creak of the back door as it slowly began to open.

Copyright © 1968 by Joan Aiken

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details