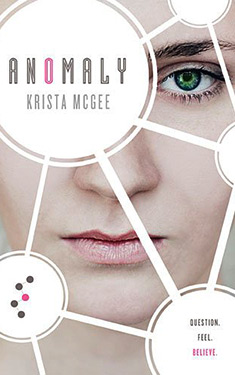

Anomaly

| Author: | Krista McGee |

| Publisher: |

Thomas Nelson, 2013 |

| Series: | Anomaly: Book 1 |

|

1. Anomaly |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Thalli has fifteen minutes and twenty-three seconds left to live. The toxic gas that will complete her annihilation is invading her bloodstream. But she is not afraid.

Thalli is different than others in The State. She feels things. She asks questions. And in the State, this is not tolerated. The Ten scientists who survived the nuclear war that destroyed the world above believe that emotion was at the core of what went wrong--and they have genetically removed it from the citizens they have since created. Thalli has kept her malformation secret from those who have monitored her for most of her life, but when she receives an ancient piece of music to record as her community's assigned musician, she can no longer keep her emotions secreted away.

Seen as a threat to the harmony of her Pod, Thalli is taken to the Scientists for immediate annihilation. But before that can happen, Berk--her former Pod mate who is being groomed as a Scientist--steps in and persuades the Scientists to keep Thalli alive as a test subject.

The more time she spends in the Scientist's Pod, the clearer it becomes that things are not as simple as she was programmed to believe. She hears stories of a Designer--stories that fill her mind with more questions: Who can she trust? What is this emotion called love? And what if she isn't just an anomaly, but part of a greater design?

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

I suppose I've always known something was wrong withme. I've never quite been normal. Never really felt like I fit.Don't get me wrong. I've tried. In fact, I spent most of my lifetrying.

Like everyone in Pod C, I was given a particular set ofskills, a job I would eventually take over from the generationbefore us.

I am the Musician of Pod C.

My purpose is to stimulate my pod mates' minds throughthe instruments I play. I enable the others to do their jobs evenbetter.

And that is important because being productive is important.Working hard is important. I have always been able to dothat. But being the same is also important.

This is where I have failed.

I started realizing this in my ninth year, the year my podmate Asta was taken away. We were outside in the recreationfield and our Monitor had us running the oval track. We rannine times--one time for each year of life. This was part of ourdaily routine.

Sometimes, I would like to say no. To just sit down, not torun. Sometimes I want to ask why we have to do this. And whywe always do everything in the same order, day after day. Whycouldn't we run ten laps? Or eight? Or skip laps altogether and dosomething else? But I knew better than to ask those questions,to ask any questions. We are only allowed to ask for clarification.Asking why is something only I would consider.

I am an anomaly.

So was Asta. But I didn't know it until that day. She alwaysdid what she was told, and nothing in her big black eyes madeher appear to be having thoughts to the contrary. She was trainingto be our pod Historian, so she was always documentingwhat we were doing and what we were discovering. Her fingerscould fly over her learning pad faster than any I'd ever seen. Butthat day, when we were running, she stopped. Right in the centerof the track. I was so shocked that I ran right into her back,knocking her to the ground.

"I apologize." I reached for her hand, but when she lookedup at me, I saw a yellowish substance coming from her nose. Ihad never seen anything like it. Her eyes were red and she waslaboring to breathe--all of this was quite unusual. I pulled myhand back and called for the Monitor to come over and helpAsta.

But the Monitor didn't help her. She looked down intoAsta's face and her eyes grew large. She pressed the panel onher wrist pad. "Please send a team to Pod C. We need a removal."

The Monitor motioned for me to finish my laps. No one elsehad stopped to see what happened. The rest of my pod matessimply ran closer to the edge of the track, eyes forward, completingthe circuit.

I stood and tried to run, but I did not want to run. I wantedto stay here, to help Asta. She looked ... I do not know how todescribe it. But whatever it was made my heart feel heavy.

Berk ran up beside me. "You will never beat me." His grinshook me from my thoughts. I was determined to beat Berk. Healways thought he was faster, but I knew I could outrun him.So I picked up my pace. Berk did the same.

We were on our fifth lap when I saw a floating white platformwith four Medical Specialists land beside Asta on thegrass inside the track. "Where will they take her?"

"I don't know." Berk slowed a little. He was watching themedics lift Asta onto the platform, then wrap her in some sort ofcovering. "Maybe take her to the Scientists. They will help her."

Berk was going to be a Scientist. One of the Scientists whogovern the State. That made him different--but in a good way.The Monitors never corrected him, and he was allowed to studyany subject that interested him during the time the rest of usworked on improving knowledge in our specialty areas.

I didn't say anything else, but the image of Asta being takenaway--removed--stayed with me. And somehow I didn't thinkshe was going to be helped. The look on the Monitor's face wasnot the look she gets when one of us falls and scrapes a knee onthe track. It was the look she gets when we do something weshouldn't. But Asta hadn't done anything wrong. She just hadsomething wrong inside her.

Like me.

A few days later I asked the Monitor if Asta would be comingback. I had worked on how I would phrase that questionfor days. It could not sound like a "why." It had to sound like Isimply wanted information, clarification. I had to sound likemy pod mate Rhen. Logical. Not emotional.

"Excuse me." I tried to ask with an air of indifference. "WillAsta be returning to Pod C?"

The Monitor did not even look up from her communicationspad. "No."

And that was all. I had to bite my lip to keep from askingwhy. I imagined all kinds of reasons. None of them made sense,and none of them, I knew, could ever be voiced.

In the quiet of our cube, I asked Rhen, "What do you thinkhappened to Asta?"

But Rhen just looked at me like she did not understand thequestion. "She was removed."

And that's all she needed to know.

When I still couldn't stop thinking about it, I asked Berk. Wewere back on the track several days after Asta's removal. "If shewent to the Scientists, why don't they fix her and send her back?"

Berk slowed his pace a little before answering. "Maybe theywill keep her with them."

"But she's our Historian." I could argue with Berk. He actuallyenjoyed it, liked questions. "They already have one of theirown."

"Whatever they are doing, it is right." This is what we havealways been taught. And, of course, it is correct.

"But I want to see her."

"When I leave to live in the Scientists' compound, I will tellher that."

That made me feel better. And worse. Better because I knewBerk would do what he said. Worse because I knew that whenhe did, I would lose another pod mate. I would lose Berk.

I did not want to think about that.

"I will win this time." I pushed all thoughts of Asta frommy mind and ran as hard as I could to the line marking the endof our circuit.

I won.

* * *

Berk left when we were twelve. It was very different from whenAsta left. Lute, our Culinary Specialist, created a pastry thatwas huge and delicious. We are rarely given pastries--theScientists say that we function best with vegetables and proteins.We are allowed fruit once a day, but pastries are only forspecial events: like Berk leaving us to begin his training withThe Ten. One day he would be one of the leaders of our State,with a variety of specialties and more knowledge than any ofus could imagine.

I always knew he would have to go. But I did not want himto. Berk was the only one who understood me. He was the onlyone who would argue with me. He let me ask questions and didnot think I was peculiar for having them.

"Will you ever come back to visit?" Berk and I sat in thegathering chamber. Everyone else had returned to their cubes.But the Monitors allowed Berk to stay. And because theyallowed Berk to do anything he wanted, they allowed me toremain behind as well.

Berk shrugged. "If I can."

I knew then he would be just like Asta--gone forever.Suddenly, my throat felt tight.

The lights flickered off.

Berk groaned. "Power outage."

It happened often. Berk was sure he could help solve thatproblem. The solar panels, he said, were overtaxed. They neededto either add more panels or find a way to use less energy. Whenhe got to the Scientists' compound, he would make solving thatproblem his priority.

Berk tapped his communications pad and the small squaremade enough light for me to see his face. He leaned close to me."I have an idea."

I could smell the soap on his skin. His teeth glowed bluefrom the light his pad cast on his face. Berk took an eating utensilfrom his pocket, scooted off the sofa, and pulled me downwith him. "No cameras." He reached under the sofa, utensil inhand, and started scratching on the ground.

"What are you doing?" I looked toward the door, makingsure no Monitors were here to see this.

"You will see." His head was on the ground, his arm as farunder the sofa as it could go. His other hand held his communicationspad. I leaned down too, but his head was in my way andI couldn't see what he was doing.

Finally, he pulled his hand out and smiled a big grin. Iwould miss that grin. "Look."

I bent down and, in the blue glow of the communicationspad, saw that he had scratched our names into the chamber'shard floor.

My eyes burned. I didn't know what was happening, but itfelt awful. Like my heart would explode and leak out, one dropat a time.

"Is it that bad?" Berk's face was in the shadows.

A tear slid down my face and Berk wiped it away with histhumb. "I will always be here." He pointed to our names, asecret testimony to our secret bond. Me, an abnormality, andhe, a leader.

The lights were back on--which meant the cameras weretoo. I stood and turned my back to the wall where the cameraswere hidden. "Good-bye, Berk."

I went back to my cube and buried my head under my covers,trying to push down the emotions threatening to spill out,like the tears that dampened my pillow and the substance, solike Asta's, that dripped from my nose. My heart felt like it wasbeing ripped out. Berk was my best friend in the whole State.And he was gone. Forever.

In the years since, I learned that when I am missing Berkor Asta, I can play my tears through my instruments. And theMonitors think I am just improving. They don't know the truth.I play laughter and frustration. I play feelings I cannot define.But the music defines them for me. I don't feel out of place whenI am playing. I feel just right. I wish I could play all the time.

But we have other responsibilities. Like right now. I am supposedto be in my cube, reading my lesson on the learning pad. Iam in my cube. And I have my learning pad. But I am using it towrite music instead. Sometimes notes come into my mind andI need to get them out, on the screen, so I can play them later.The Monitors see me doing this. I know they will come in andtell me to stop, to complete my lesson. I know this and yet hereI am, fingers flying over my pad, getting as many notes on myprogram as I can before--

"Thalli." The Monitor arrives. She is the sixth Monitor wehave had this year, although I know she has been here before.More than once. But the Monitors rotate every two months.The Scientists don't want us becoming dependent on them. TheMonitors are older than we are, from the generation before us,Pod B, and their lives will end before ours.

Productivity is key, as is peace.

The Scientists determined long ago that generations wholive and die together will be more productive and more peacefulthan those who live integrated with other generations. Sowe live only with our generation, seeing other generations onlyoccasionally and only for short periods of time.

"History." The Monitor taps on my screen and my lessonpops up. "You have free time next hour."

I wait until I hear the Monitor's sharp heels fading into thedistance, then I finally look at my screen. I don't know why Iwait. Rhen wouldn't wait. She would do exactly as she was toldright when she was told to do it. Rhen wouldn't work on musicwhen she was supposed to be studying history either.

But I am not Rhen.

History is my least favorite subject. There is nothing new.At least with the other subjects, new layers are added each year.But as I scroll through the lesson, it's exactly the same materialwe've had since we learned how to read.

"In the era before ours, the world was chaotic. People didterrible things." I look up from the pad. I would like to knowabout those terrible things. But if I even asked, I'd be takenaway for sure. No one asks questions like that. Questions likethat do not promote peace.

I look back down and pretend to read while my thoughtsrun away, back to my music. If I am being completely honest, Iknow I am flawed. But no one else has to know. I need to forcemyself not to give in to those flaws. Which means I need toforce myself to study history.

Ah yes. Terrible things. The final terror was what the Scientistscalled a Nuclear War. Something that destroyed everythingaboveground. Billions of people died in one moment.

I try to imagine billions of people. I see them as notescrammed on a pad of music, so many notes that the screen isblack with just little dots of white peeking through whole andhalf notes, shining through the crevices of the treble clef.

I must concentrate.

The only survivors were The Ten, the Scientists who nowrule the State. Before this war, they had been creating theunderground State for almost a decade because the governmentof what they called their country wanted to have something inplace to protect their rulers. The rulers never had time to make itunderground, though. But The Ten were here. They had knownthis was coming--not the Nuclear War exactly, but somethingterrible. They watched people become slaves to emotion andbe driven by conflict. The end result of emotion and conflict isdevastation.

So they decided to begin again with a State that requiredpeace, that did not allow for any conflicts so there would neverbe any wars. Emotions were limited for the same reason. Beforethe State began, children were born in a way the history lessoncalled "primitive."

"Primitive." I mouth the word, barely above a whisper. Itsounds awful. What does it mean?

Children were designed by The Ten, designed to be healthyand intelligent and know their places in the State. When theirincubation period ended, they were placed in pods with otherchildren whose incubation periods ended. Mine is the thirdgeneration of children, with each generation having just enoughcitizens to maintain productivity and fill the vacancies left bythose who were no longer productive.

Ours will never be a world of billions.

I look back at my learning pad. I can answer all the questionsat the end without having to read the information again. But thelearning pad watches my eyes, making sure I read everything,not letting me complete the evaluation until I have looked atevery word.

Finally, I finish. I return to my music when a sound eruptsin the cube next to mine. Rhen's cube.

I have heard that sound before. A long time ago.

It was the sound Asta made before she was taken away.

Rhen steps into my cube. Her nose drips a yellowish substance.

Before I can stop her, she presses the emergency button thatsummons the Monitors to our wing.

CHAPTER 2

It was my fault." I step in front of Rhen, blocking the Monitorsfrom seeing her face, her nose.

"No." Rhen's hand is on my shoulder. She wants to reportherself. It is logical--she realizes she is flawed so she mustleave.

But something greater than logic makes me stop her. I don'tknow what it is, I only know that I have lost two friends already.I cannot lose another. I cannot stand the thought of waking upevery day and not seeing Rhen in our cube.

"I hit the button." I look at the Monitors. The one who hadcome to me earlier stands beside a new one. They look almostidentical. All Monitors do. Dark hair, dark eyes, tall and thin,hair pulled away from their heads. They are designed withheightened senses of sight and hearing. Nothing escapes theirnotice.

"I didn't hear you move from your seat." The first Monitorlooks at me, her dark eyebrows lifted.

I don't say anything. Rhen looks at me, and I see the questionin her eyes. I close my own in response. We will not discussthis with the Monitors.

"You are seventeen, Thalli." The Monitor folds her arms."You must stop playing tricks. That is not acceptable anymore.Do you think the Scientists play tricks?"

Of course the Scientists do not play tricks. They work hardand they work together and they help this world to functionin perfect order and harmony. I lower my head to acknowledgethat I understand that fact and am ashamed for having beenfrivolous with my time.

Rhen breathes in deeply through her nose, the substancemaking a liquid sound as it goes up. I do the same, trying tomake a similar sound. The Monitor's look of surprise turns toone of annoyance. "Rhen, please do not allow Thalli to encourageyou to behave in ways that are unseemly for one your age."

"Of course." Rhen's voice sounds different, deeper. TheMonitors step forward. They are going to examine Rhen. I haveto do something.

"Attention, please." The wall screen lights up. I want toshout in relief. But I do not, of course. I do glance at Rhen andsmile just a little.

The Announcer's face fills the screen. His face is flawless.Announcers are plastered on our walls at least twice a day, andso they must be pleasant to look at. They all look slightly different.I like this one the best. He has hair that is a mix betweenRhen's blond and my brown. His eyes are a bright green.

Copyright © 2013 by Krista McGee

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details