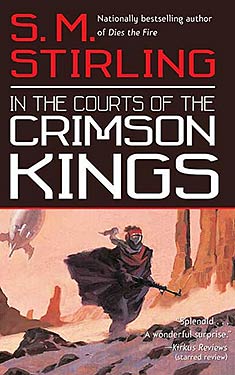

In the Courts of the Crimson Kings

| Author: | S. M. Stirling |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2008 |

| Series: | The Lords of Creation: Book 2 |

|

1. The Sky People |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Pulp Science-Fantasy Space Opera |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In the parallel world first introduced in S. M. Stirling's The Sky People, aliens terraformed Mars (and Venus) two hundred million years ago, seeding them with life-forms from Earth. Humans didn't suspect this until the twentieth century, but when the first probes landed on our sister worlds, and found life--intelligent life, at that--things changed with a vengeance. By the year 2000, America, Russia, and the other great powers of Earth are all contending for influence and power amid the newly-discovered inhabitants of our sister planets.

Venus is a primitive world. But on Mars, early hominids evolved civilization earlier than their earthly cousins, driven by the needs of a harsh world growing still harsher as the initial terraforming runs down. Without coal, oil, or uranium, their technology was forced into different paths, and the genetic wizardry of the Crimson Dynasty united a world for more than twenty thousand years.

Now, in a new stand-alone adventure set in this world's 2000 AD, Jeremy Wainman is an archaeologist who has achieved a lifelong dream; to travel to Mars and explore the dead cities of the Deep Beyond, searching for the secrets of the Kings Beneath the Mountain and the fallen empire they ruled.

Teyud Zha-Zhalt is the Martian mercenary the Terrans hire as guide and captain of the landship Intrepid Traveller. A secret links her to the deadly intrigues of Dvor il-Adazar, the City That Is A Mountain, where the last aging descendant of the Tollamune Emperors clings to the remnants of his power... and secrets that may trace their origin to the enigmatic Ancients, the Lords of Creation who reshaped the Solar System in the time of the dinosaurs.

When these three meet, the foundations of reality will be shaken--from the lost city of Rema-Dza to the courts of the Crimson Kings.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

Encyclopedia Britannica, 20th edition

University of Chicago Press, 1998

Mars--Parameters:

Orbit: 1.5237 AU

Orbital period: 668.6 Martian solar days

Rotation: 24 hrs. 34 min.

Mass: 0.1075 x Earth

Average density: 3.93 g/cc

Surface Gravity: 0.377 x Earth

Diameter: 4,217 miles (equatorial; 53.3% x Earth)

Surface: 75% land, 25% water (incl. pack ice)

Atmospheric composition:

Nitrogen 76.51%

Oxygen 20.23%

Carbon Dioxide 0.11%

Trace elements: Argon, Neon, Krypton.

Atmospheric Pressure: 0.7 psi average at northern sea level

The third life-bearing world of the Solar System, Mars is less Earthlike than Venus, although like Earth and unlike Venus its rotation is counterclockwise, and the length of the Martian day is nearly identical to that of Earth's. The atmosphere is thinner than Earth's, and is apparently growing thinner still; though it remains easily breathable for Terran humanity at the lower levels, uplands tolerable for Martians require oxygen masks of the type used by mountaineers on Earth. More significant is the fact that Mars has a thick, rigid crust which prevents the plate tectonics characteristic of the other two worlds.

Average temperatures on Mars are roughly 10 degrees Celsius lower than those on Earth, due to the lower solar energy input. This effect is moderated by the higher percentage of carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere, a phenomenon puzzling to scientists because the planet lacks plate tectonics to recirculate carbon compounds and presumably has less vulcanism. The year, twice the Terrestrial, and the greater eccentricity of the Martian orbit render seasonal contrasts greater than the Terran norm even at the equator.

Temperatures on Earth may have been in a similar range, however, at some periods of geologic time (see "Snowball Earth"). It is believed that the gradually thinning of the Martian atmosphere and hence the reduced ability to hold heat has been offset to some degree by the gradual increase in the Sun's energy output over time.

The proportions of land and water on Mars are almost a precise reversal of those on Earth. Mars has seas surrounded by land, rather than land surrounded by oceans, and so the total land area is not dissimilar to that of Earth. The bulk of the water area is concentrated in the Great Northern Sea in the northern polar zone, with a smaller equivalent in the Antarctic Sea. Smaller bodies of water are present in parts of the main equator-girdling land mass...

@@@

Mars, City of Zar-tu-Kan

Tau-il-Zhi (Tower of Truth)

May 1st, 2000 AD.

"How can you work for the vaz-Terranan? They're rich and they have some curious and powerful tembst, but by the First Principle, they're ugly!" Jelzhau said, considering the board.

He moved his Chief Coercive diagonally two squares and threatened her Despot.

The woman who called herself Teyud za-Zhalt sipped at her flask of essence through the glass straw, savoring the musky tartness of the liquid, and then moved her Flier Transport onto the same square.

The mild euphoric was doubly pleasurable since Jelzhau would be buying if she won the game, and he had never toppled her Despot in a bout of atanj yet, unless she lost deliberately.

I am glad to have found alternate employment, she thought, studying the board. He never grasped that I was occasionally throwing the game, either.

Guarding the life of someone you'd rather see dead was a means of earning your water too heavily spiced with irony for inner peace. Besides that, he was a cheapskate. Occasionally his atanj play was good enough to be entertaining, but usually...

Ah, yes. Once again, excessive conservatism in his employment of the Coercives and Clandestines. He relies too much on his Blockade and Boycott pieces, as might be expected of a spice merchant.

If you didn't exercise your Coercives, you increased the odds of their defection.

"You deal with the vaz-Terranan too," she pointed out, as he threw the dice to determine whose piece would win the battle for the square. "Extensively."

"That is a series of expeditious meetings. You have to associate with the hideous things. Ah, randomness falls out in your favor."

The dice showed three threes; that gave the paratroops in her Flier Transport time to emerge and capture his Chief Coercive.

"Oh, not necessarily so very hideous," she said, taking the dice. "Some are grotesque--like a squashed-down caricature of humanity--but some are just stocky and perhaps a bit irregular of feature and extremely muscular. The ones I've met are all rather clever, too, if naïve."

Jelzhau shuddered. "And they ooze. They're positively slick with water and mucus most of the time. You can feel it on their breath. An extra three on whether my Chief Coercive will defect?"

"Oozing would be unaesthetic," Teyud admitted. "Three, agreed."

She threw; three ones, a low-probability result. In the game, that meant her paratroopers had bribed or threatened his Chief Coercive to turn against his Despot. She moved the pieces, now both hers, into another square.

"Your Despot is now confronted," she said formally. "He must restore Sh'u Maz, or abdicate."

Jelzhau sighed and tipped over the tower-shaped piece. "He abdicates; your Despot proves superior fitness to perpetuate his lineage and establish Sustained Harmony. And as for the vaz-Terranan, they have a distinct and unpleasant odor, as well."

Her nostrils flared in irony; Jelzhau was given to excessive use of odwa-scent, himself.

"I can't detect any untoward odor most of the time. In essential respects, they resemble us--for example, they have their own internal disputes and differences."

"They all seem much alike to me."

Privately she thought the spice-factor was being a little bigoted, even if there was some truth to the physical description. The travelers from the Wet World couldn't help their semblance, and the ones from Kennedy Base usually dressed in local garb, and tried to behave in seemly fashion. Which was more than you could say of some of her own race, like that clutch of deep-chested highlander caravaneers who were singing--they probably thought it was song--over in one corner, and pawing at one of the De'ming servitors.

If you couldn't integrate an essence without losing harmony, you shouldn't partake in public.

Mind you, the Blue-tinted Time Considered As A Regressing Series was that sort of canalside dive. It had seen better days, but those had probably been when the Crimson Dynasty still ruled. Someone was neglecting the glow-globes set in the fluid-stone of the ceiling fifteen feet overhead; badly fed, they gave off less light than they should, and it had an unpleasant greenish cast that made the figures of scholars and warriors on the wall look decayed.

And there was a grease-mark on the smooth pearl granite behind her head; the taverner claimed that it had been made by the famous unbound hair of Zowej-ar-Lakrid in the Conqueror's student days fifteen hundred years ago, when he was conspiring to overthrow the city's despot while playing atanj in this very spot, and that it would be sacrilege to remove it. Some deep layer of it might indeed be that old.

For the rest, the stopping-place looked depressingly like a thousand others she'd seen, from one end of the Real World to another; a circular room on the ground floor of a tower more than half abandoned. In the more traveled places near the exits the hard green stones of the floor were worn into troughs that menaced the balance of the patrons. Deepest of all were the spots before the entrance to the spiral staircase in the center of the room.

The floor was set with circular tables of tkem-wood that had been polished blackness once and were nicked and dark-grey now.

Hers held a tiny fretted-copper brazier with a stick of cheap incense burning, and a bowl of tart dipping sauce for the small platter that had held raw rooz meat cut into strips. She took the last strip between a mannerly thumb and forefinger, touched it to the sauce and ate.

Too hot, she thought. Cheap narwak badly ground, or steeped too long.

The meat at least was decently fresh, pleasant, lightly marbled, deep-red, richly salted and slightly moist; the animal had not lost its flaps in vain.

Just then the clock over the entrance to the staircase opened its mouth, gave a sad, piercing cry and sang:

"Hours like sand

On the shores of a bitter sea

Flow on waves of time;

Seven hours have passed

Since last the Sun

Rose in blind majesty;

It shall yield heedless to night

In ten more.

One... two... three... four... five... six... seven."

That meant the flier would be arriving soon. Teyud packed her board and set, folding them into a palm-sized rectangle and slipping it into its pouch at her belt as they rose; Jelzhau would have taken the lead if Teyud had not adopted a hipshot pose of astonished sorrow. He flushed darkly and made his bow excessive.

"True, you are no longer in my employ, Most Refined of Breeding," he said.

"Indeed," she replied tranquilly, neglecting to add an honorific.

I wonder what the Wet Worlders truly think of us? she wondered idly, as they began to trot upward.

It was still hard to have a conversation with them beyond the obvious, and they were less than frank about some things. That was probably wise of them--everyone loved flattery, and criticism was rarely popular--but a pity nonetheless. They were the first new things to come into the Real World for a very long time.

Even as her father's lineage reckoned such things. And they had ruled this world for twice ten thousand years.

But they do so no longer; now they hide in ruins and brood, she reminded herself. Do not waste lifespan in reverie on things past, as your father did... does. For each being, the time from birth to death is as that of the universe itself. You are not in the Tollamune Emperor's court at Dvor Il-Adazar now... and if you were within sight of the Tower of Harmonic Unity, you would die slowly.

@@@

"This trip is the first time I've seen this many Martian faces uncovered," Jeremy Wainman said as the Zhoming Dael slowed on its approach to the tall slimness of the tower. "Here on Zho'da, that is, not in videos back Earthside."

Martians called their planet Zho'da; that meant "The Real World," or possibly "The Only Significant Place." It was all a matter of perspective, he supposed.

"It makes sense to muffle up outside on this planet," Captain Sally Yamashita, United States Aerospace Force, Astronaut Corps, said. "Dry, cold, windy, lots of acrid dust. Plus--"

The Martian airship had made several stops on its way from Kennedy Base, but those had been at caravanserais and isolated trading posts. He and his superior were the only Earthlings--vaz-Terranan in demotic Martian--in the curved forward lounge with its transparent outward-sloping wall. The dozen or so locals mostly remained seated in their nests of cushions and traveling silks and furs, many with a board between them and the eternal Martian atanj game underway; it was routine for them. Jeremy leaned eagerly over the railing, looking as the long bright line of the canal opened out into the glittering shapes of the half-ruined city ahead.

"Plus it's the custom," he said, grinning and quoting the most common phrase in the orientation lectures that had started back on Earth right after the summons he'd dreamed of but not seriously expected, and had continued at short intervals while the Brackett made its long passage out and then at Kennedy Base too.

"I am an anthropologist, you know," Jeremy added. "With a secondary degree in archaeology, to boot, and one in Martian History."

Sally nodded. She was tall by Terran standards--everyone assigned to Mars was, though like her, most were below the Martian average. But even at five-eleven, she gave an impression of close-coupled energy, and her slanted hazel eyes were very keen. Her father had been California-Japanese, richer than God and a marine biologist with a hobby in martial arts; her mother was from a long line of Napa valley winemakers but had broken the mold by going into modern dance. Her own specialty was the study of Martian technology; she had degrees in molecular biology and paleontology. But she was also a general fixer and contact person, helping Kennedy Base interface with the Martians. And she was several years older than Jeremy at thirty, with the weathered skin of an Old Mars Hand.

And... I think she's a spook. Not all the time, we're all multitasking here, but I think that's what she is if you dig down through all the layers. Why are they sending a spook on an archaeological scouting mission? Granted, this can be a very hairy planet, and she looks like she can clip hair with the best of them, but...

"You're an anthropologist... a very inexperienced anthropologist," she said.

It was his first trip outside Kennedy Base. He'd seen pictures of the these towers with their time-faded colors and the lacy crystalline bridges that joined them, the transparent domes below full of an astonishing flowering lushness, the narrow serpentine streets between blank-faced buildings of rose-red stone... but now he could see them for himself. They reminded him a little of Indian Mughal architecture done by someone on opium and freed from the limits of stone and the constraints of gravity, but there was a soft-edged quality to them unlike anything his world had ever bred, as if they had grown here.

In the distance loomed jagged heights that had been the edge of a continent when the site of this city was below the waves of a vanished sea...

Sally snorted; he had a sudden uncomfortable feeling she knew just what sort of greenhorn romantic twaddle he was thinking. Her words confirmed it.

"Even the experienced are just scratching the surface here. Venus may be full of hunter-gatherers or Bronze Age types like the Kartahownians, but this isn't Venus--the Martians were doing calligraphy and building cities forty thousand years ago. The Crimson Dynasty ruled before the Cro-Magnons painted mammoths on those caves in France, and it fell about the time we invented writing."

"We came to them, not vice versa," Jeremy pointed out. And I'm teasing you. Do you have to be sosolemn about everything?

Apparently she did. Even her nod was grave as she went on:

"We have a technological edge. Sort of, or so we like to think. But Earth's a long way away and there aren't many of us here. We can't push these people around and we don't impress them much either. I repeat: this isn't Venus. We can't play Gods-from-the-sky here. We're on sufferance. And never forget we don't know dick about this place, really."

"Yes, teacher," he said good-humoredly. "I'll try to make us a little less abysmally ignorant, hmm? We do need to start learning more about Martian history. Besides what their chronicles tell us. They don't always ask the same questions we want answered and it's always a good idea to check words against the stones and bones anyway."

"Yeah, so you talked them into sending us to do a dig at Rema-Dza. Which may or may not actually exist."

"The satellite photos show something large is there. And according to the chronicles, it could only be the city of Rema-Dza."

"Now who's relying on words? Those are chronicles after fifteen thousand years of recopying, sometimes by people who thought it was a good idea to goof on their descendants, as interpreted by contemporary Martians who sometimes like to play see-what-the-Terran-barbarians-will-swallow. I'm still not sure it was a cost-effective decision."

It was hard not to be good-humored. He'd finally made it here. He'd dreamed about it since he was old enough to distinguish the stuff on the news from the fairytales his mother had read him. He'd worked and planned and sweated and competed, but tens or hundreds of millions had shared that dream. Now he'd done it, while they went on dreaming and reading bad novels about people like him, and watching even worse movies and video shows and breathless documentaries on the National Geographic channel.

"Why are you along, then?" he asked. "We're all supposed to be able to handle stuff on our own. We have to, with a hundred-odd people to study an entire world."

Three years of lobbying, and suddenly they found the funds for me and for a survey of the lost cities of the Imperial era. God, I thought it would stay tied up in the USASF bureaucracy forever.

She snorted. "We're not supposed to be self-sufficient on our first time out! And you're a civilian."

"Yes, ma'am," he said tolerantly, with a good-natured mock salute.

If it weren't for the planetary exploration program, the Pentagon would be an afterthought these days--there hadn't been a significant international conflict since the Laotian incident in the 60′s, unless you counted occasional scuffles in backwaters like the Near East and Africa, which nobody in the real centers of civilization had spare time or energy to get involved. The competition with the Eastbloc and Eurobloc was real enough, but on a more rarefied level--civilization seemed to have outgrown direct confrontations. Most people of his university-and-sciences background thought that was an inevitable product of technological and economic progress.

"Mars and Venus are probably the reasons things are peaceful back home," Sally pointed out dryly. "But out here, things get a bit more hairy."

He nodded, not exactly in agreement, but unwillingness to argue with someone senior over a minor point. He was the one in a traveling robe woven from the exudation of jeweled moths--cloth that was Kevlar-like armor as well as clothing--with a sword by his side and a minicam and blank data chips in the haversack slung over his back. When he got back to base, the chips would have enough on them to keep Earth's scholars working for a generation. Plus there was the sense of bouncy, dreamlike enjoyment that you got under one-third gravity; he still had to remind himself now and then not to go bounding everywhere like a slow-mo grasshopper.

The Tower of Truth rose eight hundred feet above the glassine roof of the Canal Named Liquid Abundance, growing from a tiny, asparagus-stalk shape to its full immensity as the airship approached. Most of that height was a fluted smoothness of stone striated in dusky green and dark rose, broken only by tall narrow windows. The top flared out into a shape like an elongated teardrop set on its base, ringed about with circular doors large enough to take the pointed nose of an airship; the wall between each door was transparent.

One of the doors irised open as the Zhoming Dael drifted to a near stop three thousand yards away, hanging as weightless as did the dandelion-like seeds for which it was named. From above the passenger deck one of the crew sent an orok out a hatchway, a sort of domesticated eagle with a body the size of a big dog, a crest of bronze-gold feathers on its cruel raptor head and a twenty-foot wingspan. It beat its great pinions twice and then glided to the open portal with a cable in its claws, folding its wings as it stooped through the entranceway and hopped towards the ground-crew.

"You might say birds do well on Mars," Sally said.

That surprised him into a chuckle at the understatement. The lower gravity more than made up for the thinner air, and being able to migrate was a big plus here.

The long fabric of the Drifting Frozen-white Thistle Seeds jerked as hands within took the line and reeved it through geared windlasses. The ship's engines stopped; he could hear them panting for breath in the propeller pods above and behind him as the whirring hum died away. In utter silence, the huge craft slid forward until the smooth hull mated with the collar of the portal. Before him, the front of the gondola folded down to make a ramp, and the yellow-red light of Martian glow-globes shone brightly through.

The passengers stood, slung their bundles over their backs and walked forward to pay the entry toll. Zar-tu-kan's officialdom was represented by a robed figure standing by the exit next to a pillar with a slot in the top. He had a small animal like a dark furry cylinder clutched in his right hand; there was a little red rosebud mouth--or anus or possibly both--at one end, but no eyes or limbs. The customs agent held it out from his side so that the six feet of thin, pink, slowly curling naked tail was well away from his body.

You didn't want to make accidental contact with a shockwhip, even if the wielder wasn't squeezing it to turn on the current. Everyone was allergic to the proteins on its surface.

Each passenger reached into the slot and dropped something as they went by; Sally Yamashita added two inch-long pieces of silver wire.

"One tenth shem," a voice in accented Martian said, through a grill on the side of the stone post.

"Correct weight for two foreigners and up to fifteen zka-kem of noncommercial baggage," the functionary added. "You may pass."

"Doesn't anyone ever try to stiff the tax-man?" he murmured to her. "Slipping in copper for silver?"

"There's a mouth with teeth below that slot," she said. "It can taste the purity of metals with its tongue. And if the weight or composition's wrong, it bites down and holds you for Mr. Revenue Service to beat on with his Amazingly Itchy Electro-Rat."

Ouch, Jeremy thought. There are times when Martian technology is just plain... icky. And they could use a Martian Civil Liberties Union. Admittedly they don't have reallybad tyrants, but they have far too many fair-to-middling ones.

A crowd was waiting for the airship. Quietly animated bargaining started as soon as the passengers disembarked, with raised eyebrows and the occasional spare gesture doing service for shouts, insults and windmilling arms. Groundcrew brought hoses forward to clip to sockets in the Floating Thistle's nose and pump sludge aboard to feed the engines and the bacterial solution that produced hydrogen for the lifting cells. Fine sand ballast vented from the keel to compensate.

The interior of the tower here was a huge circular room with a groin-vaulted ceiling; bales and sacks and containers of cargo stood about in it, but not enough of them to prevent a feeling of dusty emptiness. The faded, half-abstract, half-pictorial frescos above the entry portals showed a traffic far thicker and more bustling... but they might be older than Western civilization, beneath their coating of impenetrable glassine. There was a faint smell in the air of things like burnt cinnamon and something halfway between hibiscus and clove, of acrid smoke, of sweat that was harsher and more concentrated than that of his breed because it wasted less water.

And somehow the scent of time, like faded memories piled in an infinite attic, layer upon layer until the present seemed no more than an image seen in a dream.

"Our contact?" he said.

"Jelzhau Zhau-nor. He's a big wheel in the Zhau-na, the spice-merchant's guild."

"It's not really a--" Jeremy began automatically.

"Guild. Or clan. Kin-group, corporation, thingie, whatever--"

"Thingie won't do for the Journal of Martian Cultural Studies."

"Don't the younger generation have any respect for their elders these days?"

"Did you, mother dear?"

"No, but I had an excuse--I was rebelling against my Japanese heritage. Anyway, we buy from him."

Jeremy nodded. Martian spices and drugs--they didn't distinguish the concepts in Demotic--did things to the taste buds, metabolism and nerves that Terrestrial science was having problems understanding. They were the only things besides information that could really show a profit after interplanetary shipping costs; gold and gems didn't even come close.

One of them was a genuine anti-agathic, slowing down aging for Martians and probably for Terrans too, though that would take time to prove. Particularly since Martians had about twice the Terran life-span anyway, and the metabolisms of the two species were similar but not identical.

"And he's got contacts everywhere. He's the one who hires our guides for us."

Two Martians came forward and took greeting stances ten yards away--which meant, between those of roughly equal status, something that looked like shaking hands with yourself. Martians certainly didn't shake hands with each other; this culture put a premium on social distance.

And the gesture was the local equivalent of waving, whistling between your teeth and shouting, Hey, Mac!

He and Sally returned the signal. One of the Martians was a man who looked middle-aged--which probably meant he was pushing a hundred, in Earth-years--and who equaled Jeremy's own six-six height. That was average for standard Martians, though they varied less than humans that way. His smooth, beardless skin was pale olive, and the oiled hair dressed in elaborate curls was raven-black, also common. His robe was striped white and dark green, and the leather of his belt and curl-toed boots nearly shimmered with enameled inlay work.

The woman beside him made Jeremy's eyes go a little wider. She was over seven feet tall, with even more of the big-eyed aquiline delicacy of features than most Martians, but looking more solid, somehow.

Less as if she'd blow away in a stiff wind, he thought.

The color of those huge eyes was distinctly odd, yellow as fire, and so was the almost bronze sheen of hair caught back in a fine metallic net. There was an eerie loveliness to the alien face...

"Hey," he whispered in English. "You didn't tell me our guide was--"

"--of the old Thoughtful Grace caste. They were--"

"The Crimson Dynasty's military elite, yes," Jeremy said. "The caste just below the top."

For God's sake! he thought. I'm not an ignoramus because I arrived on the Brackett six months ago and this is my first off-base field trip. I've been studying Mars since I was twelve!

He didn't say it. There were too few Terrans on Mars to let quarrels grow, even with the selection for stable types. And you were stuck with the same people for the rest of your life; only two people had returned to Earth from Mars in nearly twenty years. Tiny Kennedy Base off on the shores of the Bitter Sea wasn't a real frontier settlement like growing Jamestown on Venus, but it would be his home for a very long time to come. He'd made that decision when he'd walked through the suddenly open door.

Sally shrugged apologetically for the same reasons. "I didn't know it would be her this time; there are a couple who we use regularly. Mostly hunters and caravan guards."

"I didn't know there were any purebred Thoughtful Grace left, at least not outside the Wai Zang towns," he said, professional interest growing in his face. "And that's along way away."

"Hell, my specialty is Martian technology."

"Just that," Jeremy said dryly.

Biotech from this planet was revolutionizing a dozen industries on Earth, from waste disposal to fuel production. The powers-that-were viewed archaeology and cultural studies mainly as a means to get the Martians to cough up their knowledge, and to figure out ways of keeping them from lynching or poisoning or infecting the irritatingly inquisitive Wet Worlders.

"I just know enough of the cultural ins and outs not to get killed. Yet." With a wry twist to her mouth: "At least they're more likely to listen to you on short acquaintance, you God-damned beanpole."

The labor gang squatting on the many-footed cargo pallets trotting forward to the flier's freight ramp were the reason for her complaint. They were De'ming, bred for menial labor by the geneticists--or possibly wizards--of the Crimson Dynasty era. They didn't really look like Earth-humans; they were just thick-bodied and short by this planet's standards, enough that they were well within the Terran bell-curve. That was enough to get anyone below six feet perceived as inherently stupid and servile here.

And I don't like their eyes. There's nobody home there.

Their kind had been working with that same placid, witless docility for the last thirty thousand earth-years or so, just smart enough to take simple directions...

Icky. Really, really icky.

Jelzhau Zhau-Nor tucked his hands into the sleeves of his robe and came to about twice the conversational distance a North American considered comfortable and cocked his ears forward; they were a bit larger and a bit more elongated than a Terran's, and a whole lot more mobile.

That was a let's get down to business signal.

"I profess amiable greetings, Respectably Wealthy Jelzhau Zhau-Nor," Sally said politely in Demotic. "Intent and event produced timely arrival. Mutual delight and profit will probably follow."

"Hello, my friend Jawen Yama-shita!" he replied, in English.

With only a few hundred personnel on the planet, the US-Commonwealth-Organization of American States base could afford to be very selective, but it was still difficult to find people who met all the other qualifications and were that tall. Not only was Jeremy Wainman six-six, he had a fencer's physique, long-limbed and with a wiry muscularity; his face was handsome in a beak-nosed fashion that would last well after he passed his thirtieth year next April. His blue eyes and close-cropped dark-brown hair would be accepted as merely exotic.

Make thatsort of in English, Jeremy thought.

The sounds were difficult for Martians. At least for speakers of Modern Demotic--the only spoken language on the planet, as far as they'd been able to discover, though there were different dialects. Which simplified things considerably, since learning it made picking up Japanese look easy and Chinese a walk in the park.

Christ, it's fun to get out andreally use all that language training.

Then the factor went on in his own tongue: "You have met the highly bred Professional Practitioner of Coercive Violence, Teyud za-Zhalt."

And 'highly bred' means exactly the same thing as saying highly bred about a racehorse, and it's a compliment in this language.Professional Practitioner of Coercive Violence covers cops, soldiers and bandits.

Minds with a profound understanding of linguistics had been at work shaping Martian for a very long time.

All that in a hand gesture and three words, one of them a proper name. It's a bitch to learn, but I love this language! It's so... smooth.

The woman inclined her head slightly and laid her ears back, a gesture of respect to an employer or patron from someone equal in eugenic rank... which was a courteous assumption. Her breed had been lords once.

"My blades are ready, my guns are fully fed and loaded, other necessary equipment and personnel have been procured, and I command the directional template for our journey of exploration, employer," Teyud said to Sally, adding the last in Deferential Mode.

Her voice was beautifully modulated, a little deeper than the normal Martian soprano; if a bronze bell had been precisely machined by computer-directed lasers, it would sound like that. And her accent was noticeably different from that of the spice merchant.

Perhaps her diction is a bit... crisper? And there's something about the way she handles sibilants, too. Wait a minute--it's like the way the pillar-with-teeth spoke... archaic, maybe? A dialect from some out of the way place that hasn't changed much? I've got to get to know her well enough to ask questions!

Then she turned to him. "Identity? Skill? Status?"

"Jeremy Wainman," he said. "Scholar, of variation in custom through time; a partner to Sally, of lesser seniority."

She moved her lips slowly, then surprised him by pronouncing his name nearly as he had.

"Jeremy Wainman, my subsidiary employer, I profess amiable greetings. May randomness produce positive outcomes for you in this period of endeavor, and malice be absent."

@@@

Mars, City of Dvor Il-Adazar (Olympus Mons)

Ringing Depths Reservoir Control

January 1st, 2000 AD.

"What do you see?" Sajir-sa-Tomond said to the Terran named Franziskus Binkis. "What amuses you?"

He had held the shrunken dominions of the Ruby Throne for two hundred Martian years; in Terran terms, he had been born in the year Elizabeth the First was crowned at Westminster. Those centuries of experience and the Crimson Dynasty's inheritance gave him composure with Binkis, despite the... extremely odd way the vas-Terranan and his companion had arrived here in the depths of the City That Is A Mountain.

On balance, I am content that I did not kill him when I found him in the Shrine.

Binkis chuckled again. The pumps throbbed in the icy dimness of the great cavern; it had begun as a volcanic bubble, and been shaped to other purposes very long ago. The sound of Binkis' amusement was lost among the harsh raw power of the sound, and there was a disturbing flicker to his light-colored eyes. He was six feet tall and lanky for his breed, which made him a little shorter than average and squat to Martian eyes. The Emperor was a foot taller, and mantis-gaunt by comparison.

"Incongruity," Franziskus said. "I appreciate the incongruities."

His hand moved slightly to indicate the brute angularity of the Earth-made reactor amid the flowing organic machinery that Martians built--or more usually, grew.

"And yet," the Terran--

Who is no longer entirely a Terran, or even entirely a man, Sajir sa-Tomond reminded himself. He has been touched by the things of the Most Ancient, and carried across space and time by them.

--went on, "I also see in my mind devices that are not machines at all but relations, contiguities of time and space as complex as the dance of neurons in a brain and as abstract as a mathematical theorem. Both these technologies are as crude as wooden spear hardened in a campfire by comparison."

Sajir heard the clearing of the throat behind him. He turned; it was one of the EastBloc diplomats... Lin Yu-Pei.

He had arrived in conventional wise; by what the vas-Terranan called nuclear rocket to orbit around Mars, and then by lander dropping on a tail of fire to the field at the Mountain's foot, where Sajir sa-Tomond had allowed the EastBloc base to be erected. The diplomat was as diminutive as a De'ming and interestingly different from Binkis in physical type, but Sajir had found him clever enough despite first appearances.

Though now he is... modified. His mind now edits reality and does not perceive Binkis at all.

And there were the guards in their insectile black armor, drifting like ghosts as they moved to keep the Tollamune, Sajir sa-Tomond the Two Hundredth and Twenty-Fifth, from any risk.

A little further back, a knot of officials stood with their hands in the sleeves of robes gorgeous in red and purple, precious metals and jewels like banked embers, but cunningly patched and repaired, great-eyed faces blank beneath round caps worked in filigree. The golden traceries of their headgear were rotten and blackened with age, the emblems of vanished provinces, of services that had once spanned the planet. The air of the great, arched chamber was cold and faintly damp--sopping, to the Martians.

Sajir sa-Tomond adopted a posture of permission, turning the palms of his hands forward and then back, and the functionaries glided forward, moving in the formal pacing that made their robes seem to slide across the pavement without a hint that legs and feet moved them rather than wheels.

Lin Yu-Pei was sweating; probably because of the incongruity between what his eyes were seeing and what the script implanted within his brain would let him perceive. But then, Terrans sweated so readily...

And the elderly of the Real World let their minds lose focus. Attention to the present, Sajir sa-Tomond!

Even with the Tollamune genes and the finest antiagathics he was old, slimness turned gaunt, raven hair gone white, hawk-face deeply seamed with a mesh of wrinkles that moved and interlaced like cracks in spring ice among the northern seas. The bleak golden eyes were hooded and pouched but keen.

"Yes, the water of the Great Lower Reservoir once more flows to the distribution chambers," he said. "This is a highly desirable occurrence both in contemplation and accomplishment. Sh'u Maz! Let harmony be sustained!"

The room echoed with the response to his command: "Sh'u Maz!"

The ritual was comforting. Sajir sa-Tomond used it to calm himself as he considered:

My reaction to Binkis is odd. Any of my people who addressed me so would be infected immediately with larvae of the most malignant breed. Yet I do not even resent the fact that I may not order it in his case. There is... something else present, with this one. In the legends of the most ancient beginnings... and yes, he arrived here in a mostextraordinary manner. A fortunate randomness. Through him I may hope to recover the Ancient tembst; and even if I do not, his advice has enabled me to reverse the intent of the EastBloc Terrans that I be their puppet.

At his nod, High Minister Chinta sa-Rokis moved in a smooth arc and touched a finger cased in metal fretwork to a spot on one of the great crystal pipes that ran from floor to ceiling like pillars, a spot where a flow-gauge circled the clear tube. Her cap proclaimed her Supervisor of Planetary Water Control; in ancient days, that had been a post second only to the Commander of the Sword of the Dynasty in the planet's government.

Currently, it meant managing the municipal works and the stretch of canals immediately adjacent to the Mountain. Unlike most of the High Council, she still had someactual function.

"Three hundred ska-flow per second," the monitor said, in a dialect of Demotic so ancient it was almost the High Tongue; it had been a long time since this reservoir was active.

"Purity is within acceptable limits for all standard use. Flow has been steady for one hour, seven minutes, twenty-two seconds at the-"

The words stopped and a brief pure tone rang out.

"A remarkable display of power," Sajir said. "To raise fluid from such depths."

Chinta sa-Rokis hissed slightly; or that might have been the long slender black-furred symbiont coiled around neck and shoulder, whose lips whispered next to her ear. Then the bureaucrat spoke, while the creature stared at the Emperor with what might have been curiosity... or a predator judging distance.

"Yet how long will this--" she made a mangled attempt at pronouncing pebble-bed reactor "-continue to function? A mere five or six decades without more fuel than that store which our allies of the Wet World have supplied; and the machinery itself is not self-reproducing or self-repairing, as our accustomed tembst is. As the one tasked with maintaining the long-term supplies of water, I must--deferential mode--caution of the disruption which will arise among those dependent on the additional flow when it ceases in so brief a time."

"We have the water now," Sajir said. "Water to bring life and wealth, to pay Professional Coercives, to overcome irksome limitations."

"Even so, Supremacy--extreme deferential mode, with emphasis on non-ironic intent--problems of management present themselves."

"Death presents one with few managerial dilemmas, yet it is generally believed to be less desirable than the wearisome complications of continued existence," Sajir remarked dryly.

"I will implement the Tollamune will," Chinta said, adopting a pose of submissive obedience.

"This is generally considered a corollary of high office beneath the Tollamune Emperors," Sajir said, his tone even more pawky. "And we shall, of course, put a program in motion to duplicate the reactor and its fuel."

Chinta sa-Rokis blinked in astonishment. Nor was she the only one. He saw some of the others casting dumfounded glances at each other, and sighed inwardly. The idea might well never have occurred to him if Binkis had not suggested it, along with making the delivery of the reactor and spare fuel pellets a condition of EastBloc access to Dvor Il-Adazar's anti-agathics and anti-virals.

Aloud he continued, "The vaz-Terranan have only had this tembst a matter of fifty or sixty of their years, which are half the length of the Real World's. Prior to a similar number of our years, they were unaware of even the basic principles upon which this device functions. Surely we, with the principles in our minds, can expect our savants to duplicate the accomplishments of the Wet World?"

And surely Chinta will not publicly denigrate our capabilities? he thought with satisfaction. In fact, I am not entirely confident. Our savants have merely recirculated known data for a very long time.

The High Minister was capable, once prodded into action, but no more inclined to act on her own than a sessile-stage canal shrimp was to swim. Usually this was convenient; he could simply set her in motion in a chosen direction and then turn his attention elsewhere while she ran on rails like a cargo cart in a mine. When innovation was required, on the other hand...

And I myself am most unlikely to survive such a period at this point in my probable lifespan. Odd, to foresee personal extinction from natural causes in so brief a time as a few decades. I must learn to hurry, as if I were once again heedless with youth. This is an inconvenience. So many problems resolve themselves spontaneously with a mere twenty or thirty years of patience. On the other hand, I must keep in mind that death from another's volition is possible at any point on one's personal world-line.

"Such is the Tollamune will!" he stated in the imperative-condescentive tense.

There was only one possible public response to that. The officials lifted fingertips to their temples, bowed their heads, and chanted in chorus:

"King Beneath the Mountain! Crimson King, holding and swaying the Real World!"

They would draw the small sharp knives in their sleeves and slit their throats in ritual Apology if he commanded. But just as the portion of the Real World he in fact commanded was much smaller than theory suggested, so would they still conspire and intrigue with every breath they drew to bend his will to theirs. The more so as he aged towards the ultimate limits and had no immediate heir. That, too, was a situation without precedent, but not one they seemed to find difficult to enter into their calculations.

No heir save for her. And some of them realize with horror that if my plans succeed, they will have functional duties once more. A balance is required.

He was tempted to give the order for a mass Apology in any case, but their probable successors would be no more reliable, and far more energetic and hungry. Best to keep these for the present. Their underlings had had many years of waiting, which would keep the ministers looking both upward and downward. Younger replacements would be positioned securely enough with their subordinates to look only towards him.

The most advantageous circumstance of being at the summit is the added velocity of the downward kick; next, the fact that there is nobody above one to do the same...

"I am glad that Your Supremacy is pleased with our fraternal aid," Lin Yu-Pei said, eyes flickering as he struggled to follow the conversation in Court Demotic.

He was rather obviously translating too literally from his native speech; he had been Ambassador for only a few years. The attrition rate from incompatible proteins made the implantation risky with vaz-Terranan. The courtiers tensed very slightly, adopting postures of disassociation, implying that they were not present. The guards reacted in a more unambiguous fashion, touching weapons.

"That is not the most appropriate of phrasing," Sajir said gently.

"Your Supremacy?"

Sajir sa-Tomond fell into the Terran language called Russian; they had a ridiculous number of languages, and used them all simultaneously, but it was an ability he had thought sufficiently useful to cultivate. Communication beyond the basics required more than translation of words; modes of thought and perception embodied in the underlying syntax must be understood.

"You implied a genetic relationship with myself, the Tollamune," he explained gently. "This is a serious breach of protocol and may not be done even as a matter of metaphor. Further, you did not use the metaphorical mode."

"My apologies, your Supremacy,"

"While not forgotten, the offense is allowed to pass without repercussion due to your ignorance of the Real World's usages," Sajir said formally.

Unnoticed by the Terran diplomat, the Expediter of Painful Transitions lowered the grub-implanter.

"Concerning the treaty--"

Binkis giggled and uttered two command code words. Lin jerked and stood stock still. Just below where his spine met his skull something glistened for a moment as it moved.

"-thank you, Your Supremacy," Lin continued. "I request permission to return to my quarters. I... I have matters to consider."

"Permission is granted with formal expressions of amiable goodwill. Let harmony be sustained!"

Binkis giggled again as the Terran walked away, shaking his head as if bothered by some annoying parasite... which, considering the ancestry of the implant, was not too far from the truth. Sajir sa-Tomond gestured in a manner that meant anticipated reaction. Since Binkis was possibly possessed by the ancient entities, but was certainly a Terran with limited appreciation of the High Speech, he added aloud:

"How long before they begin to suspect? Eventually the knowledge that a Terran who did not arrive by spaceship is at my court will reach them. Not all are suitably infected by the neural controller. The high rate of fatalities is an inconvenience; the new model is still prone to prompting severe allergic reactions."

"They already suspect something. It will not matter if we can interface your ancestors' devices fully with the Terran powerplant, their numerically driven controllers, and also with their weapons."

"Ah, yes, the explosives dependent on deconstruction of nuclei in a feedback cycle and the expanding-combustion-gas propulsive missiles," Savir said. "I am still somewhat dubious. Reducing territory to toxic dust seems... excessive if one wishes to control it."

"A few examples will produce submission."

"A good point. Force is always more effectively employed as threat than actuality; the greater the raw strength, the more this is so."

"And they will give you leverage against the EastBloc... against Terra as a whole. They were designed to counter possible USASF action; they have that capacity against EastBloc ships as well. You will effectively dominate space near Mars."

"True. There remains the problem of the interface, though. New devices are required. Mere selective breeding, or even enzymatic recombinant splicing of the cellular mechanisms of existing machinery is not sufficient; my savants are definite and unanimous, and my own judgment is the same. The very mathematics are different, and require neural devices of novel types, incorporating the target algorithms. The theory needed to produce such is known; practical implementation of such ceased very long ago."

"You have the original cell-mechanism modification devices. The Tollamune genome will activate them."

Ahmm, Sajir thought. He still longs for the repair of his consort, who arrived with him.

The Terran woman was quite mad; only a form of synthetic hibernation had preserved her life this long. The Ancient-derived devices probably would suffice, if only it were possible to use them.

He frowned thoughtfully before he spoke. "There is a reason they have not been employed in so very long. They are very old, they have been used intensively without maintenance and as a result, they are... stressful. My genes are correct; my endurance, however, has diminished to the point where further contact would endanger my life."

And that is all you need to know. The true secret, you do not know, nor shall you.

He turned and left; etiquette did not require anything further for the Emperor, of course. His back still crawled slightly, as if in anticipation of the knife or the needle...

Yet that is one of my most familiar sensations, he thought. I cannot recall a time beyond infancy when it was not chronic. We have preserved the consensual myth of the absolute authority of the Tollumune Throne for so long, yet was it ever more than literalized metaphor? Not in the opinion of my ancestors, certainly. And most certainly, not since the loss of the Invisible Crown.

The elevator was a bubble of warmth and color and light after the dank dimness of the pumping chamber. It had been repaired and resurfaced for his visit, and the murals were pleasantly pastoral; they showed small, four-legged creatures with silky fur and overlapping rows of teeth gamboling through reeds beside a lake while the tentacles of predatory invertebrates prepared attack. Idly, he wondered if the place still existed; probably not. The small creatures were extinct save for preserved genetic data, and so were the invertebrates except in derived weapon- and execution-forms.

"Rise to the Imperial Quarters level," the captain of his bodyguards said--though this shaft was a dedicated one.

The elevator began to hum quietly as it rose through the Tower of Harmonic Unity. The tune was soothing but a little banal, though it covered the quick panting of the engine as it worked the winch on the traveling chamber's roof. The ride was water-smooth otherwise; the engine had been replaced with a fresh budding as well, and the rails and wheels greased by lubricant crawler. The smooth efficiency was bitterly pleasant, as if he had fallen back through the ages, as if all Dvor Il-Adazar were so, drawing on the resources of a world. When it stopped, he pressed a hand to a plate that was warm and slightly moist; it pulsed as it tasted him and identified the Imperial genome.

When the door dilated and he walked through into his sanctum, the present returned on padding feet; murals ever so slightly faded...

One wall was glassine, as clear as ever and at the three-thousand-foot level. It showed the slopes of the western cliffs tumbling away below, carved into tower and dome, bridge and roadway, as far north and south as vision could reach. They had been wrought from living rock black and tawny and golden, but always framed in the blood-red that had given his lineage its name. Beyond stretched the Grand Canal that circled the huge volcanic cone and collected the water its height raked from the sky. On either side of the canal lay the greenish-red and blue-green of life, with here and there the soaring white pride of a magnate's villa.

Fliers drifted past, lean, crimson patrol-craft, diminutive yachts with fanciful paint, plain, fat-bodied freighters; riders mounted on Paiteng swooped and soared among them. Landships by the hundred waited by the docks, or sailed the ochre-colored turf of the passageways that led through the croplands to the deserts beyond. Behind him rose the Mountain itself, towering near seventy thousand feet above, through layers of garden and forest and glacier, and then on to the thin verges of space.

If Dvor Il-Adazar was only a city-state now, it was at least the greatest that yet remained in the Real World... though from here you could not see how many towers and courts sheltered only dust and silence and fading legends. If the empty ones were fewer than they had been in the year of his accession, then the credit was his, the long struggle against entropy.

"Attend me," he said to the guard-commander, and led the way into the Chamber of Memories.

A flick of a finger brought attendants who left essences and a bowl of smoldering stimulative and then withdrew. Sajir sa-Tomond sat in a lounger that adjusted to his frail length and began to administer warmth and massage. The room was neither very large nor very grand, except for the single block of red crystal shaped into a seat against the far wall; there was only one other like that in all existence, in the Hall of Received Submission.

He stared moodily at it as he sipped. The essence gave him the semblance of strength, and he closed his eyes for a moment to settle his mind. A game of atanj lay on a board before him, each piece carved from a single thumb-sized jewel or shaped from precious metal: ruby and jet for the Despots, black jade for the Clandestines, tourmaline for the Coercives, gold fretwork and diamond for the Boycotts.

"Sit," he said to the Coercive. "Unmask. Refresh yourself. You have not made a move today."

The commander did, raising the visor of his parade helm with its faceted eyes and golden mandibles. When the Tollamune opened his own eyes once more, sorrow pierced him to the heart at the sight of the face beneath, the steady golden eyes and the bronze hair in its jeweled war-net. So like, so like...

The Thoughtful Grace moved immediately; a Transport leaping a Boycott to deliver a cargo.

Ahmm! Sajir thought. Daring, yet clever. I will not win this game in less than twenty-three moves now.

"I have a task for you, Notaj sa-Soj," he said softly.

"Command me, Tollamune," the man said.

The voice was different from hers, a little deeper, a little older--Vowin sa-Soj had been only fifty at the beginning of her long and bitter death. Notaj sa-Soj was her sire's youngest brother by another breeding partner, and at a century young for his post. His eugenic qualifications were impeccable, and his record of action matched it.

"To recapitulate that which is universally known but rarely expressed: I have no heir," Sajir said. "None of more than one-eight consanguinity, and none of sufficient genetic congruity to be accounted of the Lineage or to operate the Devices. With me, the Crimson Dynasty ends, after eighteen thousand years of the Real World, and all hope of restoring Sh'u Maz in its true form."

"This is true, Supremacy. With you will perish the significance of our existence and such meaning as sentience has imposed on mere event. There is little consolation in it, but the line of the Kings Beneath the Mountain will at least end with a superior individual."

The nicating membranes swept over Notaj' eyes, leaving them glistening. "I will preserve your life as long as event and randomness permit, your Supremacy," he added, his voice firm.

Despite everything, Sajir sa-Tomond felt himself smile at the harmonics that underlay the flat statement. The voice of a Thoughtful Grace purebred could rarely be read for undertone... by anyone but a Tollamune.

"At least, the official perception of matters is that I have no heir of closer than one-eighth consanguinity," Sajir said, and saw the other's pupils flare and ears cock forward.

Their breed had been selected for wit, not merely deadliness. They had been generals and commanders once, as well as matchless Coercives on a personal level. The implications and possibilities needed little restating.

"Vowin's offspring survives?"

"Correct, captain. Concealed here until relatively recently. When she matured, traces of the Tollamune inheritance became unmistakable."

They shared a glance that said: And then she must be hidden and exiled, for what crime is more reprobated than the theft of the Tollamune genome? But now, perhaps, the balance of forces allows...

"The knowledge is no longer so closely held as would best suit my purposes," Sajir went on. "You will understand that multiple factions wish the official and perceived reality to be made objective truth, lest the pleasantly empty field left after my long-anticipated departure should prove not so empty after all."

"But you do not so wish, Supremacy?" the guard captain said, his voice neutral as the cool water in the fountain.

"I never did." Sajir's eyes closed again, this time against remembered pain. "As evidence, she lives."

"But Vowin does not--interrogative-hypothetical?"

"Certain courses of action were... necessary. If she had waited longer to make herself receptive to fertilization, as I instructed... But you of the Thoughtful Grace are... headlong. And there was doubt as to my own survival at the time. The arrival of the vas-Terranan machines disturbed a most delicate balance."

Notaj blinked, integrating the information. "She must have been willing to undertake death by infestation in order to secure the Lineage," he said; there was a hard pride in his tone. "She was, as you say, youthful and headlong, but a fine strategic analyst, and ruthless. And genetically ambitious. To bear the first outcross of the Tollamune line in ten millennia..."

Sajir sa-Tomond let his shoulders and head fall into a pose of acceptance. "So she said. Such pride was worthy of eugenic elevation. We of the Dynasty have hugged our seed too close, to the detriment of Sh'u Maz."

The guardsman gestured agreement-with-reservations; unspoken was the reason for that--the tools of power responded to the genome, not the individual. Too many Emperors had died at the hands of their own close kin for any to forget it. So their numbers had dwindled across the millennia and their own long lifespans.

As have the water and atmosphere of the Real World itself, Sajir thought. This is a congruity far too apt for comfort.

"There are many factors to be considered," Notaj said. "Your demise would, with a high degree of probability, be... expedited... if an heir were anticipated, but not yet in place and aligned with effective power. Those disaffected elements content to wait now for their chance would act precipitately in that hypothesis."

"True. Therefore the heir must be found, brought to Dvor Il-Adazar, and put in an unassailable position. Those who wish to kill or capture her--"

"Capture her?"

Both words were separately in Interrogative; the guardsman raised two fingers to his brow in apology. Sajir sa-Tomond moved a hand in a gentle curve that covered his words in a glow of affection:

"The offspring was female. And there is the vas-Terranan to be considered. There are implications of possession of the Tollamune genome that you do not know; suffice it to say that the Terran requires access to the genome. Prince Heltaw sa-Veynau, for example, wishing to rule through a puppet and gain access to the Tollamune genome. Possibly others, but certainly him."

"The Terran?"

"Him. Unfortunately, he is necessary to my purposes. And I very much depreciate the high-probability consequences of his no longer needing me."

"I will begin contingency planning immediately," Notaj said. "The necessary information, Supremacy--identity and location?"

He gave the data--keys to the files, rather--and watched the brisk efficiency of the commander's stride out of the entrance with wry amusement.

Then the man halted and turned in the doorway, his eyes going to the atanj board.

"Twenty-five moves, Supremacy."

That also reminded him of a woman dead many years.

His loyalty is absolute, though intelligent and independent, the Tollamune thought. And now I have activated his own lineage ambitions. He will operate at maximum efficiency. To promote this is to sustain harmony.

With a sigh he rose from the recliner and walked to the crystal throne. Eddies moved within the dense redness of it, like wings of gauze. He gave a complex shiver as he sat, resting his head against the recess behind it and feeling the featherlight pressure against the scar on his neck, then a slight sting. Exterior reality vanished. A murmur as of distant hive-insects seemed to fill his skull, but it was no mere vibration of the air. An inexpressible sensation of draining, as his recent memories joined those of all his life, and of the lineage of the Crimson Dynasty and their consorts since the beginning.

Visions: death, birth, love, hate, accomplishment and cruelty, glory and despair. The bowed heads of ancient kings kneeling before the First Emperor; the feel of his own blood pouring out over the crystal, and the knives in the hands of kin. The temptation to lose himself in that endless sea was strong and bitter, as strong as the taste of tokmar; he knew that, for a memory of it was here--not his, many generations removed, but as real as the weary weight of his own bones.

"For a moment," he whispered. "Only for a moment I will see you again, my Vowin, so beautiful and so fierce. Then I will fight for the child of our union, until we are united once more."

Copyright © 2008 by S. M. Stirling

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details