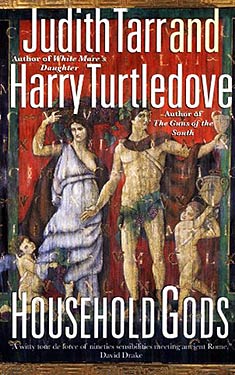

Household Gods

| Author: | Harry Turtledove Judith Tarr |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 1999 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Time Travel |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Nicole Gunther-Perrin is a modern young professional, proud of her legal skills but weary of childcare, of senior law partners who put the moves on her, and of her deadbeat ex-husband. Following a ghastly day of dealing with all three, she falls into bed asleep - and awakens the next morning to find herself in a different life, that of a widowed tavernkeeper in the Roman frontier town of Carnuntum around 170 A.D.

Delighted at first to be away from corrupt, sexist modern America, she quickly begins to realise that her new world is as complicated as her old one. Violence, dirt, and pain are everywhere - and yet many of the people she comes to know are as happy as those she knew in twentieth-century Los Angeles. Slavery is a commonplace, gladiators kill for sport, and drunkenness is taken for granted - but everyday people somehow manage to face life with humour and good will.

No quitter, Nicole manages to adapt to her new life despite endless worry about the fate of her children "back" in the twentieth century. Then plague sweeps through Carnuntum, followed by brutal war. Amid pain and loss on a level she had never imagined, Nicole finds reserves of strength she had never known.

Excerpt

1

NICOLE GUNTHER-PERRIN ROLLED over to turn off the alarm clock and found herself nose to nose with two Roman gods. She nodded a familiar good morning to Liber and his consort Libera, whose votive plaque had stood on the nightstand since her honeymoon in Vienna. Maybe they nodded back. Maybe she was still half asleep.

As she dragged herself up to wake the children and get them ready for daycare, her mouth twisted. Liber and Libera were still with her. Frank Perrin, however ...

"Bastard," she said. Liber and Libera didn't look surprised. They'd heard it every morning since her ex-husband took half the assets, left the kids, and headed off for bluer horizons. She doubted he thought about her except when the child support came due (and not often enough then), or when she called him with a problem. She couldn't help thinking of him a dozen times a day--and every time she looked at Justin. Her son--their son, if you wanted to get technical--looked just like him. Same rough dark hair, down to the uncombable cowlick; same dark eyes you could drown in; same shy little smile that made you feel you'd coaxed it out of hiding.

Justin smiled it as she gently shook him awake. "Mommy!" he said. He was only two and a half. He hadn't learned to wound her yet.

"Come on, Tiger," she said in her best rise-and-shine, mommy-in-the-morning voice. "We've got another day ahead of us." She reached inside his Pull-Ups. "You're dry! What a good boy! Go on and go potty while I get your sister up."

He climbed onto the rail and jumped out of bed. He landed with a splat, of course, but it didn't hurt him. It made himlaugh. He toddled off sturdily toward the bathroom. Watching him go, Nicole shook her head. Kimberley never jumped out of bed. Testosterone poisoning, Nicole thought, and almost smiled.

Kimberley not only didn't jump out of bed, she didn't want to get out of bed at all. She clutched her stuffed bobcat and refused to open her eyes. She was like that about every other morning; given her druthers, she would have slept till noon. She didn't have her druthers, not on a Tuesday. "You've got to get up, sweetie," Nicole said with determined patience.

Eyes still resolutely closed, Kimberley shook her head. Her light brown hair, almost the same color as Nicole's, streamed over her face like seaweed. Nicole wheeled out the heavy guns: "Your brother is already up. You're a big four-year-old. You can do what he does, can't you?" If she'd used such shameless tactics in court, counsel for the other side would have screamed his head off, and the judge would have sustained him.

But she wasn't in court, and there was no law that said she had to be completely fair with a small and relentlessly sleepy child. She did what she had to do, and did it with a minimum of remorse.

It worked. Kimberley opened her eyes. They were hazel, halfway between Frank's brown and Nicole's green. Still clutching her beloved Scratchy, Kimberley headed for the bathroom. Nicole nodded to herself and sighed. Her daughter wasn't likely to say anything much for the next little while, but once she got moving, she moved pretty well.

Nicole got moving, too, toward the kitchen. Her brain was running ahead of her, kicked up into full daytime gear. She'd get the kids' breakfasts ready, get dressed herself while they ate, listen to the news on the radio while she was doing that so she could find out what traffic was like (traffic in Indianapolis had not prepared her for L.A., not even slightly), and then ...

And then, for the first time that day, her plans started to unravel. Normally silent Kimberley let out a shrill screech:"Ewwww!" Then came the inevitable, "Mommmmy!" Ritual satisfied, Kimberley deigned to explain what was actually wrong: "Justin tinkled all over the bathroom floor and I stepped in it. Eww! Eww! Eww!" More ewws might have followed that last one, but, if so, only dogs could hear them.

"Oh, for God's sake!" Nicole burst out; and under her breath, succinctly and satisfyingly if not precisely accurately, "Shit."

The bathroom was in the usual morning shambles, with additions. She tried to stay calm. "Justin," she said in the tone of perfect reason recommended by all the best child psychologists and riot-control experts, "if you go potty the way big boys do, you have to remember to stand on the stepstool so the tinkle goes in the potty like it's supposed to."

Children raised in psychologists' laboratories, or rioting mobs, might have stopped to listen. Her own offspring were oblivious. "Mommy!" Kimberley kept screaming. "Wash my feet!" Justin was laughing so hard he looked ready to fall down, though not, she noticed, into the puddle that had sent Kimberley into such hysterics. He thought his big sister in conniptions was the funniest thing in the world--which meant he'd probably pee all over the floor again sometime soon, to make Kimberley pitch another fit.

Nicole gave up on psychology and settled for basic hygiene. She coaxed the still shrieking Kimberley over to the tub and got her feet washed, three times, with soap. Then, with Kimberley hopping on one foot and screeching, "Another time, Mommy! I'm still dirty! I smell bad! Mommy, do it again!" Nicole got the wriggling, giggling Justin out of his wet pajama bottoms and the pulled-down Pull-Ups he was still wearing at half mast. She washed his feet, too, on general principles, and his legs. He'd stopped giggling and started chanting: "Tinkle-Kim! Tinkle-Kim!"--which would have set Kimberley off again if she'd ever stopped.

Nicole's head was ringing. She would be calm, she told herself. She must be calm. A good mother never lost hercool. A good mother never raised her voice. A good mother--

She had to raise her voice. She wouldn't be heard otherwise. "Go out in the hall, both of you!" she bellowed into sudden, unexpected silence, as Kimberley finally stopped for breath. She added, just too late: "Step around the puddle!"

Something in her face must have got through Justin's high glee. He was very, very quiet as she washed his feet again, his big brown eyes fixed on her face. From invisible foot-washer to Mommy Monster in five not-so-easy seconds. She took advantage of it to send him out to the kitchen. Unfair advantage. Bad parenting. Blissful, peaceful quiet.

"Guilty as charged, Your Honor," she said.

While she was cleaning up the mess, she got piss on one knee of her thirty-five-dollar, lace-trimmed, rose-printed sweats--Victoria's Secret called them "thermal pyjamas," which must have been a step up the sexiness scale from sweats, but sweats they were, and sweats Nicole called them.

She emerged somewhat less than triumphant and wrapped in the ratty old bathrobe that hung on the back of the door, to find Kimberley, who still hadn't had a chance to go to the bathroom, hopping up and down in the hallway. At least she was quiet, though she dashed past Nicole with a theatrical sigh of relief.

Ten minutes wasted, ten minutes Nicole didn't have. She popped waffles in the toaster, stood tapping her foot till they were done, poured syrup over them, poured milk (Justin's in a Tommee Tippee cup, so he'd have a harder time spilling that on the floor), and settled the kids down--she hoped--for breakfast. Justin was still bare-ass. He laughed at the way his bottom felt on the smooth vinyl of the high chair.

As she turned on Sesame Street, Nicole muttered what was half a prayer: "Five minutes' peace." She hurried back past the study into her own bedroom to dress. About halfway into her pantyhose (control tops, because at thirty-four she was getting a little round in the middle and she didn't have time to exercise--she didn't have time for anything), Kimberley'svoice rose once again to a banshee shriek. "Mom-meeeee! Justin's got syrup in his hair!"

Nicole felt her nail poke into the stockings as she yanked them all the way up. She looked down. Sure as hell, a run, a killer run, a ladder from ankle to thigh. She threw the robe back around herself, ran out to the kitchen, surveyed the damage--repaired it at top speed, with a glance at the green unblinking eye of the microwave-oven clock. Five more minutes she didn't have.

Once back in the dubious sanctuary of her bedroom, she took another ten seconds of overdraft to stop, breathe, calm down. Her hands were gratifyingly steady as she found and put on a new pair of hose, a white blouse, and a dark green pinstripe suit that not only looked professional but also, she hoped, played up her eyes. The skirt was a bit snug but would do; she'd go easy on the Danish this morning, and leave the sugar out of her coffee--if she got the chance to eat at all. She slid into mocha pumps, pinned on an opal brooch and put in the earrings that went with it, and checked the effect. Not bad, but she was late, late, late. She still had to get the kids dressed, put on her makeup, and maybe even grab breakfast for herself. She was past morning mode by now, past even Panic Overdrive, and into dead, cold calm.

Kimberley knew she didn't want to wear the Magic Mountain sweatshirt Nicole had picked out for her, but had no idea what she did want. Nicole had hoped to hold onto her desperate calm, but that drove her over the edge. "You figure it out," she snapped, and left Kimberley to it while she went to deal with Justin. He didn't care what he wore. Whatever it was, getting him into it was a wrestling match better suited to Hulk Hogan than a working mother.

After Nicole pinned him and dressed him, she went in search of Kimberley. Her daughter hadn't moved. She was still standing in the middle of her pink-and-white bedroom, in her underwear, staring at a tangled assortment of shirts, pants, shorts, and skirts. Nicole felt her hands twitch in an almost irresistible urge to slap. She forced herself to stop and draw a breath, to speak reasonably if firmly. "We don't haveany more time to waste, young lady." In spite of her best efforts, her voice rose. "Here. This shirt. These pants. Now."

Sullenly, Kimberley put them on. "I hate you," she said, and then, as if that had been a rehearsal, found something worse: "Daddy and Dawn never yell at me."

Only four, and she knew just where to stick the knife.

Nicole stalked out of her daughter's bedroom, tight-lipped and quivering with rage she refused to show. As she strode past the nightstand on her way into the master bathroom, she glared at Liber and Libera--especially at Liber. The god and goddess, their hair cut in almost identical pageboy bobs, stared serenely back, as they had for ... how long?

She grasped at that thought--any straw in a storm, any distraction before she lost it completely. The label on the back of the limestone plaque said in German, English, and French that it was a reproduction of an original excavated from the ruins of Carnuntum, the Roman city on the site of Petronell, the small town east of Vienna where she'd bought it. Every now and then, she wondered about that. None of the other reproductions in the shop had looked quite so ... antique. But none of the Customs men had given her any grief about it. If they didn't know, who did?

As a distraction, it was a failure. When she stood in front of the makeup mirror, the modern world came crashing back. Fury had left her cheeks so red, she almost decided to leave off the blusher. But she knew what would happen next: the blood would drain away and leave them pasty white, and she'd look worse than ever. When she'd done the best she could with foundation and blusher, eyeliner and mascara and eyebrow pencil, lip liner and lipstick, she surveyed the results with a critical eye. Even with the help of modern cosmetology, her face was still too round--doughy, if you got right down to it. Anyone could guess she was a schnitzel-eater from a long line of schnitzel-eaters. She was starting to get a double chin, to go with the belly she had to work a little harder each year to disguise with suit jackets and shirtdresses and carefully cut slacks. And--what joy!--she was gettinga pimple, too, right in the middle of her chin, a sure sign her period was on the way.

"Thirty-four years old, and I've got zits," she said to nobody in particular. God wasn't listening, that was plain. She camouflaged the damage as best she could, corralled the kids, and headed out to the car.

The Honda coughed several times before reluctantly kicking over. If Frank had got the last child-support check to her, or the one before that, she'd have had it tuned. As things were--as things were, she gritted her teeth. She was a lawyer. She was supposed to be making good money. She was making good money, by every national standard, but food and daycare and clothes and insurance and utilities and the mortgage ate it all up and then some.

House payments in Indianapolis hadn't prepared her for Los Angeles, either. With two incomes, they were doable. Without two incomes ...

"Yay! Off to Josefina's," Kimberley said when they pulled out of the driveway. Apparently, she'd forgotten she hated her mother.

Nicole wished she could forget as easily as that herself. "Off to Josefina's," she echoed with considerably less enthusiasm. She lived in West Hills, maybe ten minutes away from the splendidly multicultural law offices of Rosenthal, Gallagher, Kaplan, Jeter, Gonzalez & Feng. The daycare, provider, however, was over in Van Nuys, halfway across the San Fernando Valley.

That hadn't been a problem when Nicole was married. Frank would drop off the kids, then head down the San Diego Freeway to the computer-science classes he taught at U.C.L.A. He'd pick Kimberley and Justin up in the evening, too. Everything was great. Josefina was wonderful, the kids loved her, Nicole got an extra half-hour every morning to drink her coffee and brace herself for the day.

Now that Frank didn't live there anymore, Nicole had to drive twenty minutes in the direction opposite the one that would have taken her to work, then hustle back across theValley to the Woodland Hills office. After she got off, she made the same trip in reverse. No wonder the Honda needed a tuneup. Nicole kept wanting to try to find someone closer, preferably on the way to work, but the kids screamed every time she suggested it, and there never seemed to be time. So she kept taking them to Josefina's, and the Honda kept complaining, and she kept scrambling, morning after morning and evening after evening. Someday the Honda would break down and she'd scream loud enough to drown out the kids, and then she'd get around to finding someone else to take care of them while she went about earning a living.

She turned left onto Victory and headed east. Sometimes you could make really good time on Victory, almost as good as on the freeway--the freeway when it wasn't jammed, of course; the eastbound 101 during morning rush hour didn't bear thinking about. She hoped this would be one of those times; she was still running late.

She sailed past the parking lots of the Fallbrook Mall and the more upscale Topanga Plaza. Both were acres of empty asphalt now. They wouldn't slow her down till she came home tonight. Her hands tightened on the wheel as she came up to Pierce College. Things often jammed there in the morning, with people heading for early classes. Some of the kids drove like maniacs, too, and got into wrecks that snarled traffic for a mile in either direction.

Not today, though. "Victory," Nicole breathed: half street name, half triumph. Victory wasn't like Sherman Way, with a traffic light every short block. Clear sailing till just before the freeway, she thought. She rolled by one gas station, apartment house, condo block, and strip mall with video store or copy place or small-time accountant's office or baseball-card shop or Mexican or Thai or Chinese or Korean or Indian or Armenian restaurant after another, in continual and polyglot confusion. They had a flat and faintly unreal look in the trafficless morning, under the blue California sky.

Six years and she could still marvel at the way the light came down straight and white and hard, with an edge to it that she could taste in the back of her throat. Good solid LosAngeles smog, pressed down hard by the sun: air you could cut pieces off and eat. She'd thought she'd never be able to breathe it, gone around with a stitch in her side and a catch in her lungs, till one day she woke up and realized she hadn't felt like that in weeks. She'd whooped, which woke up Frank; then she'd had to explain: "I'm an Angeleno now! I can breathe the smog."

Frank hadn't understood. He'd just eyed her warily and grunted and gone to take over the bathroom the way he did every morning.

She should have seen the end then, but it had taken another couple of years and numerous further signs--then he was gone and she was a statistic. Divorced wife, mother of two.

She came back to the here-and-now just past White Oak, just as everything on the south side of the street turned green. The long rolling stretch of parkland took her back all over again to the Midwest--to the place she'd taught herself to stop calling home. There, she'd taken green for granted. Here, in Southern California, green was a miracle and a gift. Eight months a year, any landscape that wasn't irrigated stretched bare and bleak and brown. Rain seldom fell. Rivers were few and far between. This was desert--rather to the astonishment of most transplants, who'd expected sun and surf and palm trees, but never realized how dry the land was beyond the beaches.

There was actually a river here, the Los Angeles River, running through the park. But the L.A. River, even the brief stretch of it not encased in concrete, would hardly have passed for a creek in Indiana. She shut down a surge of homesickness so strong it caught her by surprise. "Damn," she said softly--too softly, apparently, for the kids to hear: no voice piped up from the back, no "Damn what, Mommy?" from Justin and no prim "We don't use bad words, Mommy," from Kimberley. She'd thought she was long past yearning for Indiana. What was there to yearn for? Narrow minds and narrower mindsets, freezing cold in the winter and choking humidity in the summer, and thousands of miles to the nearest ocean.

And green. Green grass and bare naked water, and air that didn't rake the lungs raw.

Just past Hayvenhurst, everything stopped. A red sea of brake lights lay ahead, and she had no way to part it. She glared at the car radio, which hadn't said a word about any accidents. But the traffic reports seldom bothered with surface-street crashes; they had enough trouble keeping up with bad news on the freeways.

"Why aren't we going, Mommy?" Kimberley asked from the backseat, as inevitable as the traffic jam.

"We're stuck," Nicole answered, as she'd answered a hundred times before. "There must be an accident up ahead."

They were stuck tight, too. With the park on one side of Victory and a golf course on the other, there weren't even any cross streets with which to escape. Nothing to do but fume, slide forward a couple of inches, hit the brakes, fume again.

People in the fast lane were making U-turns to go back to Hayvenhurst and around the catastrophe that had turned Victory into defeat. Nicole, of course, was trapped in the slow lane. Whenever she tried to get into the fast lane, somebody cut her off. Drivers leaned on their horns (which the Nicole who'd lived in Indianapolis would have been surprised to hear was rare in L.A.), flipped off their neighbors, shook fists. She wondered how many of them had a gun in their waistband or pocket or purse or glove compartment. She didn't want to find out.

Ten mortal minutes and half a mile later, she crawled past the U-Haul truck that had wrapped itself around a pole. The driver was talking to a cop. "Penal Section 502," she snarled, that being the California section on driving under the influence.

She had to slow down again as cars got onto the San Diego Freeway, but that happened every day. She bore it in resigned annoyance as a proper Angeleno should, but with a thrum of desperation underneath. Late-late-late ...

Once she got under the overpass, she made reasonablydecent time. Thoughts about locking the barn door after the horse was stolen ran through her mind.

Parts of Van Nuys were ordinary middle-class suburb. Parts were the sort of neighborhood where you wished you could drive with the Club locked on the steering wheel. Josefina's house was right on the edge between the one and the other.

"Hello, Mrs. Gunther-Perrin," Josefina said in accented English as Nicole led her children into the relative coolness and dimness of the house. It smelled faintly of sour milk and babies, more distinctly of spices Nicole had learned to recognize: cilantro, cumin, chili powder. The children tugged at Nicole's hands, trying to break free and bolt, first into Josefina's welcoming arms, then to the playroom where they'd spend most of the day.

Normally, Nicole would have let them go, but Josefina had put herself in the way, and something in her expression made Nicole tighten her grip in spite of the children's protests.

Josefina was somewhere near Nicole's age, several inches shorter, a good deal wider, and addicted to lurid colors: today, an electric blue blouse over fluorescent orange pants. Her taste in clothes, fortunately, didn't extend to the decor of her house; that was a more or less standard Sears amalgam of brown plaid and olive-green slipcovers, with a touch of faded blue and purple and orange in a big terracotta vase of paper flowers that stood by the door. Nicole would remember the flowers later, more clearly than Josefina's face in the shadow of the foyer, or even the day-glo glare of her clothes.

Nicole waited for Josefina to move so that Kimberley and Justin could go in, but Josefina stood her ground, solid as a tiki god in a Hawaiian gift shop. "Listen, Mrs. Gunther-Perrin," she said. "I got to tell you something. Something important."

"What?" Nicole was going to snap again. Damn it, she was late. How in hell was she going to make it to the office on time if the kids' daycare provider wanted to stop and chat?

Josefina could hardly have missed the chill in Nicole'stone, but she didn't back down. "Mrs. Gunther-Perrin, I'm very sorry, but after today I can't take care of your kids no more. I can't take care of nobody's kids no more."

She did look sorry. Nicole granted her that. Was there a glisten of tears in her eyes?

Nicole was too horrified to be reasonable, and too astonished to care whether Josefina was happy, sad, or indifferent. "What?" she said. "You what? You can't do that!"

Josefina did not reply with the obvious, which was that she perfectly well could. "I got to go home to Mexico. My mother down in Ciudad Obreg6n, where I come from, she very sick." Josefina brought the story out pat. And why not? She must have told it a dozen times already, to a dozen other shocked and appalled parents. "She call me last night," she said, "and I get the airplane ticket. I leave tonight. I don't know when I be back. I don't know if I be back. I'm very sorry, but I can't help it. You give me the check for this part of the month when you pick up the kids tonight, okay?"

Then, finally, she stood a little to the side so that Kimberley and Justin could run past her. They seemed not to know or understand what she'd said, which was a small--a very small--mercy. Nicole stood numbly as they vanished into the depths of the house, staring at Josefina's round flat face above the screaming blue of her blouse. "But--" Nicole said. "But--"

Her brain was as sticky as the Honda's engine. It needed a couple of tries before it would turn over. "But what am I supposed to do? I work for a living, Josefina--I have to. Where am I supposed to take the children tomorrow?"

Josefina's face set. Nicole damned herself for political incorrectness, for thinking that this woman whom she was so careful to think of as an equal and not as an ethnic curiosity, looked just now like every stereotype of the inscrutable and intractable aborigine. Her eyes were flat and black. Her features, the broad cheekbones, the Aztec profile, the bronze sheen of the skin, were completely and undeniably foreign. Years of daycare, daily meetings, little presents for the children on their birthdays and plates of delicious and exoticcookies at Christmas, reciprocated with boxes of chocolates--Russell Stover, not Godiva; Godiva was an acquired taste if you weren't a yuppie--all added up to this: closed mind and closed face, and nothing to get a grip on, no handhold for sympathy, let alone understanding. This, Nicole knew with a kind of angry despair, was an alien. She'd never been a friend, and she'd never been a compatriot, either. Her whole world just barely touched on anything that Nicole knew. And now even that narrow tangent had disappeared.

"I'm sorry," Josefina said in her foreign accent, with her soft Spanish vowels. "I know you are upset with me. Lots of parents upset with me, but I can't do nothing about it. My mother got nobody else but me."

Nicole made her mind work, made herself think and talk some kind of sense. "Do you know anyone who might take Kimberley and Justin on such short notice?"

God, even if Josefina said yes, the kids would pitch a fit. She was ... like a mother to them. That had always worried Nicole a little--not, she'd been careful to assure herself, that her impeccably Anglo children should be so attached to a Mexican woman; no, of course not, how wonderfully free of prejudice that would make them, and they'd picked up Spanish, too. No, she worried she herself wasn't mother enough, so they'd had to focus on Josefina for all the things Nicole couldn't, but should, be offering them. And now, when they were fixated like that, to go from her house to some stranger's--

Even as Nicole fussed over what was, after all, a minor worry, Josefina was shaking her head. "Don't know nobody," she said. She didn't mean it the way it sounded. Of course she didn't. She couldn't mean, It's no skin off my nose, lady. Josefina loved the kids. Didn't she?

What did Nicole know of what Josefina felt or didn't feel? Josefina was foreign.

Nicole stood on the front porch, breathing hard. If that was the way Josefina wanted to play it, then that was how Nicole would play it. There had to be some way out. She would have bet money that Josefina was an undocumentedimmigrant. She could threaten to call the INS, get her checked out, have her deported ...

Anger felt good. Anger felt cleansing. But it didn't change a thing. There wasn't anything she could do. Deport Josefina? She almost laughed. Josefina was leaving the USA on her own tonight. She'd probably welcome the help.

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Gunther-Perrin," Josefina repeated. As if she meant it. As if she even cared.

Nicole didn't even remember going from the house to the car. One moment she was staring at Josefina, hunting for words that wouldn't come. The next, she was in the Honda, slamming the driver's-side door hard enough to rattle the glass in the window frame. She jammed the key in the ignition, shoved the pedal to the metal, and roared out into the street.

Part of her wanted to feel cold and sick and a little guilty. The rest of her was too ferociously angry to care how she drove.

She might not care, but with the luck she was running, she'd pick up a ticket on top of being drastically late. She made an effort of will and slowed down to something near a reasonable speed. Her brain flicked back into commuter mode, cruising on autopilot. The main part of her mind fretted away at this latest blow.

I can't worry about it now, she told herself over and over. I'll worry about it after I get to the office. I'll worry about it tonight.

First she had to get to the office. When she came out onto Victory, she shook her head violently. She knew too well how long tooling back across the western half of the Valley would take. Instead, she swung south onto the San Diego Freeway: only a mile or two there to the interchange with the 101. Yes, the eastbound 101 would be a zoo, but so what? Westbound, going against rush-hour traffic, she'd make good time. She didn't usually try it, but she wasn't usually so far behind, either.

Thinking about that, plotting out the rest of her battle plan, helped her focus; got her away from the gnawing worryabout Josefina's desertion. It was good for that much, at least.

As she crawled down toward the interchange, she checked the KFWB traffic report and then, two minutes later, the one on KNX. They were both going on about a jackknifed big rig on the Long Beach Freeway, miles from where she was. Nobody said anything about the 101. She swung through the curve from the San Diego to the 101 and pushed the car up to sixty-five.

For a couple of miles, she zoomed along--she even dared to congratulate herself. She'd rolled the dice and won: she would save ten, fifteen minutes, easy. She'd still be late, but not enough for it to be a problem. She didn't have any appointments scheduled till eleven-thirty. The rest she could cover for.

She should have known it wouldn't be that easy. Not today. Not with her luck.

Just past Hayvenhurst, everything stopped. "You lying son of a bitch!" Nicole snarled at the car radio. It was too much. Everything was going wrong. It was almost as bad as the day she woke up to a note on her pillow, and no Frank. Dear Nicole, the note had said, on departmental stationery yet, Dawn and I have gone to Reno. We'll talk about the divorce when I get back. Love, Frank. And scribbled across the bottom: P.S. The milk in the fridge is sour. Remember to check the Sell-By date next time you buy a gallon.

Remembering how bad that day was didn't make this one feel any better. "Love, Frank," she muttered. "Love, the whole goddamn world."

Her eye caught the flash of her watch as she drummed her fingers on the steering wheel. Almost time for the KNX traffic report. She stabbed the button, wishing she could stab the reporter. His cheery voice blared out of the speakers: "--and Cell-Phone Force member Big Charlie reports a three-car injury accident on the westbound 101 between White Oak and Reseda. One of those cars flipped over; it's blocking the number-two and number-three lanes. Big Charlie says only the slow lane is open. That's gonna put a hitch in your get-along,folks. Now Louise is over that jackknifed truck on the Long Beach in Helicop--"

Nicole switched stations again. Suddenly, she was very, very tired. Too tired to keep her mad on, too tired almost to hold her head up. Her fingers drummed on the wheel, drummed and drummed. The natives, she thought dizzily, were long past getting restless. Her stomach tied itself in a knot. What to do, what to do? Get off the freeway at White Oak and go back to surface streets? Or crawl past the wreck and hope she'd make up a little time when she could floor it again?

All alone in the passenger compartment, she let out a long sigh. "What difference does it make?" she said wearily. "I'm screwed either way."

She pulled into the parking lot half an hour late--twenty-eight minutes to be exact, if you felt like being exact, which she didn't. Grabbing her attaché case, she ran for the entrance to the eight-story steel-and-glass rectangle in which Rosenthal, Gallagher, Kaplan, Jeter, Gonzalez & Feng occupied the sixth and most of the seventh floors.

When she'd first seen it, she'd harbored faint dreams of L.A. Law and spectacular cases, fame and fortune and all the rest of it. Now she just wanted to get through the day without falling on her face. The real hotshots were in Beverly Hills or Century City or someplace else on the Westside. This was just ... a job, and not the world's best.

Gary Ogarkov, one of the other lawyers with the firm, stood outside the doorway puffing one of the big, smelly cigars he made such a production of. He had to come outside to do that; the building, thank God, was smoke-free. "Nicole!" he called out in what he probably thought was a fine courtroom basso. To Nicole, it sounded like a schoolboy imitation--Perry Mason on helium. "Mr. Rosenthal's been looking for you since nine o'clock."

Jesus. The founding partner. How couldn't he be looking for Nicole? That was the kind of day this was. Even knowing she'd had it coming, she still wanted to sink through thesidewalk. "God," she said. "Of all the days for traffic to be god-awful--Gary, do you know what it's about?" She pressed- him, hoping to hell he'd give her a straight answer.

Naturally, he didn't. "I shouldn't tell you." He tried to look sly. With his bland, boyish face, it didn't come off well. He was within a year of Nicole's age but, in spite of a blond mustache, still got asked for ID whenever he ordered a drink.

Nicole was no more afraid of him than the local bartenders. "Gary," she said dangerously.

He backed down in a hurry, flinging up his hands as if he thought she might bite. "Okay, okay. You look like you could use some good news. You know the Butler Ranch report we turned in a couple of weeks ago?"

"I'd better," Nicole said, still with an edge in her voice. Antidevelopment forces were fighting the Butler Ranch project tooth and nail because it would extend tract housing into the scrubby hill country north of the 118 Freeway. The fight would send the children of attorneys on both sides to Ivy League schools for years, likely decades, to come.

"Well, because of that report--" Gary paused to draw on his cigar, tilted his head back, and blew a ragged smoke ring. "Because of that report, Mr. Rosenthal named me a partner in the firm." He pointed at Nicole. "And he's looking for you."

For a moment, she just stood there. Then she felt the wide, crazy grin spread across her face. Payoff--finally. Restitution for the whole lousy morning, for a whole year of lousy mornings. "My God," she whispered. She'd done three-quarters of the work on that report. She knew it, Gary knew it, the whole firm had to know it. He was a smoother writer than she, which was the main reason he'd been involved at all, but he thought environmental impact was what caused roadkill.

"Shall I congratulate you now?" he asked. His grin was as broad as Nicole's.

She shook her head. She felt dizzy, bubbly. Was this what champagne did to people? She didn't know. She didn't drink. Just as well--she had to be calm, she had to be mature. Shecouldn't go fizzing off into the upper atmosphere. She had a reputation to uphold. "Better not," she said. "Wait till it's official. But since you are official--congratulations, Gary." She thrust out her hand. He pumped it. When he started to give her a hug, she stiffened just enough to let him know she didn't want it. Since Frank walked out the door, she hadn't wanted much to do with the male half of the human race. To cover the awkward moment, she said, "Congratulations again." And hastily, before he could say anything to prolong the moment: "I'd better get upstairs."

"Okay. And back at you," Ogarkov added, even though she'd told him not to. She made a face at him over her shoulder as she hurried toward the elevators. She almost didn't need them, she was flying so high.

When she'd floated up to the sixth floor, her secretary greeted her with a wide-eyed stare and careful refusal to point out that she was--by the clock--thirty-three minutes late. Instead, she said in her breathy Southern California starlet's voice, "Oh, Ms. Gunther-Perrin, Mr. Rosenthal's been looking for you."

Nicole nodded and bit back the silly grin. "I know," she said. "I saw Gary downstairs, smoking a victory cigar." That came out with less scorn than Nicole would have liked. She had as little use for tobacco as she did for alcohol, but when you made partner, she supposed you were entitled to celebrate. "Can he see me now, Cyndi?"

"Let me check." The secretary punched in Mr. Rosenthal's extension on the seventh floor, where all the senior partners held their dizzy eminence above the common herd, and spoke for a moment, then hung up. "He's with a client. Ten-thirty, Lucinda says."

Cyndi down here, Lucinda up above. Even the secretaries' names were more elevated in the upper reaches.

Nicole brought herself back to earth with an effort. "Oh," she said. "All right. If Lucinda says it, it must be so."

Nicole and Cyndi shared a smile. Sheldon Rosenthal's secretary reckoned herself at least as important to the firm asthe boss. She was close enough to being right that nobody ever quite dared disagree with her in public.

Something else caught Nicole's eye and mind, which went to show how scattered she still was after her morning from hell. She pointed to the photographs on her secretary's desk. "Cyndi, who takes care of Benjamin and Joseph while you're here?"

"My husband's sister," Cyndi answered. She didn't sound confused, or wary either. "She's got two-year-old twins of her own, and she stays home with them and my kids and her other sister-in-law's little girl. She'd rather do that than go back to work, so it's pretty good for all of us."

"Do you think she'd want to take on two more?" Nicole tried to make it sound light, but couldn't hide how hard Josefina's desertion had hit.

Cyndi heard the story with sympathy that looked and sounded genuine. "That's terrible of her, to spring it on you like that," she said. "Still, if it's family, what can you do? You can't very well tell your mother not to be sick, you have to stay in the States and take care of other people's kids." She hesitated. Probably she could feel Nicole staring at her, thinking at her--wanting, needing her to solve the problem. "Look," she said uncomfortably. "I understand, I really do. You know? But I don't think Marie would want to sit any kids who aren't family, you know what I mean?"

Nicole knew what she meant. Nicole would have felt the same way. But they were her kids. She was left in the lurch, on a bare day's notice. "Oh, yes," she said. She hoped she didn't sound as disappointed as she felt. "Yes. Of course. I just thought ... well. If my family were here, and not back in Indiana ...Oh well. It was worth a try." She did her best to make her shrug nonchalant, to change the subject without giving them both whiplash. "Ten-thirty, you said? I'll see what I can catch up on till then. Lord, you wouldn't believe how long it took me to get here this morning."

"Traffic." Cyndi managed to make it both a four-letter word and a sigh of relief. Off the hook, she had to be thinking.

Lucky Cyndi, with her sister in town and not in Bloomington, and no chance of her disappearing into the wilds of Ciudad Obregón. Nicole mumbled something she hoped was suitably casual, and retreated to her desk. She was still riding the high of Ogarkov's news, though the bright edge had worn off it.

The first thing she did when she got there was check her voice mail. Sure enough, one of the messages was from Sheldon Rosenthal, dry and precise as usual: "Please arrange to meet with me at your earliest convenience." She'd taken care of that. Another one was from Mort Albers, with whom she had the eleven-thirty appointment. "Can we move it up to half-past ten?" he asked.

"No, Mort," Nicole said with a measure of satisfaction, "you can't, not today." It was just as satisfying to have Cyndi make the call and change the schedule--the pleasure of power. Nicole could get used to that, oh yes she could. Even the little things felt good today. Tomorrow, she thought. Tomorrow she'd be doing them as a partner. Today--her last day as a plain associate--had a bittersweet clarity, a kind of farewell brightness. She answered a couple of voice-mail messages from other lawyers at the firm. She wrote a memo, fired it off by e-mail, and printed out a hard copy for her files. Frank would have gone on for an hour about how primitive that was, but the law ran on paper and ink, not electrons and phosphors--and to hell with Frank anyhow, she thought.

It was going to feel wonderful to tell him she was a partner now. Even if--

She quelled the little stab of anxiety. He had to keep paying child support, as much as he ever did. That was in the divorce decree. She was a lawyer--a partner in a moderately major firm. She could make it stick.

The clock on the wall ticked the minutes away. At ten twenty-five she started a letter, hesitated, counted up the minutes remaining, saved the letter on the hard drive and stood up, smoothing wrinkles out of her skirt. She checked her pantyhose. On straight, no runs--thanks to whichever god oversaw the art of dressing for success. She took a deepbreath and squared her shoulders, and forayed out past Cyndi's desk. "I'm going to see Mr. Rosenthal," she said--nice and steady, she was pleased to note. Cyndi grinned and gave her a thumbs-up.

Nicole took the stairs to the seventh floor. Some people walked all the way up every day; others exercised on the stairs during breaks and at lunch. Nicole never had understood that, not in a climate that made you happy to go outside the whole year round--even on days when the smog was thick enough to asphyxiate a non-smog-adapted organism. People who'd been born in L.A. didn't know when they were well off.

She stood in the hallway for a minute and a half, so she could walk into Sheldon Rosenthal's office at ten-thirty on the dot. It was an exercise in discipline, and a chance to pull herself together. She thought about ducking into a restroom, but that would have meant heading back down to the sixth floor: she didn't--yet--have the key to the partners' washroom. Her makeup would have to look after itself. Her bladder would hold on till the meeting was over.

Then, after what felt like a week and a half, it was time. She licked her dry lips, stiffened her spine, and walked through the mock-oak-paneled door with its discreet brass plaque: Sheldon Rosenthal, Esq., it said. That was all. No title. No ostentation. Noble self-restraint.

That restraint was, in its peculiar way, as much in evidence inside as out. Of course the office was a lot more lavishly appointed than anything down on her floor: acres of deep expensive carpet, gleaming glass, dark wood, law books bound in red and gold. But it was all in perfect taste, not overdone. It was a perk, that was all, a symbol. Here, it said, was the founding partner of the firm. Naturally he'd surround himself with order and comfort, quiet and expense, rather than the cheap carpet and tacky veneer of the salaried peon.

Lucinda Jackson looked up from the keyboard of--of all things--an IBM Selectric. Not for her anything as newfangled as a computer. She was a light-skinned black woman, the exact shade of good coffee well lightened with cream.She might have been fifty or she might have been seventy. One thing Nicole did know: she'd been with Mr. Rosenthal forever.

"He still has the client in there, Ms. Gunther-Perrin," she said. Her voice was cultured, soft, almost all traces of the Deep South excised as if by surgery. "Why don't you sit down? He'll see you as soon as he can."

Nicole nodded and sank into a chair so plush, she had real doubts that she'd be able to climb out of it. Her eyes went to the magazines on the table next to it, but she didn't take one. She didn't want to have to slap it shut all of a sudden when she received the summons to the inner office.

Twenty minutes slid by. Nicole tried to look as if she didn't mind that her life--not to mention her day's work--had been put on hold. When she was a partner, she would be more careful of her schedule. She wouldn't keep a fellow partner waiting.

At last, with an effect rather like the parting of the gates of heaven in a Fifties movie epic, the door to the inner office opened. Someone her mother had watched on TV came out. "Thanks a million, Shelly," he said over his shoulder. "I'm glad it's in good hands. Say hi to Ruth for me." He waggled his fingers at Lucinda and walked past Nicole as if she'd been invisible.

She was almost too bemused to feel slighted. Shelly? She couldn't imagine anyone calling Sheldon Rosenthal Shelly. Certainly no one in the firm did--not even the other senior partners.

"Go on in, Ms. Gunther-Pernn," Lucinda said, at the same time as Rosenthal said, "I'm sorry to have kept you waiting."

"It's all right," Nicole said, carefully heaving herself up and out of that engulfing chair. It wasn't all right, not really, but she told herself it was--the way hazing is, a kind of rite of passage. And after all, what could she do? Complain to his boss?

Rosenthal held the door open so that she could enter his sanctum. He looked like what he was: a Jewish lawyer--thin and thoughtful type, not fat and friendly--in his mid-sixties,out of the ordinary only in that he wore a neat gray chin beard. He waved her to a chair. "Please--make yourself comfortable." Before she could sit down, however, he pointed to the Mr. Coffee on a table by the window. "Help yourself, if you like."

The mug on his desk was half full. Nicole decided to take him up on his offer--a show of solidarity, as it were; her first cup of coffee as a partner in the firm. She filled one of the styrofoam cups by the coffee machine. When she tasted, her eyebrows leaped upward. "Is that Blue Mountain?" she asked.

"You're close." He smiled. "It's Kalossi Celebes. A lot of people think it's just as good, and you don't have to rob a bank to buy it."

As if you need to rob a bank, Nicole thought. Her office window looked out on the street, and on the office building across it. His offered a panorama of the hills that gave Woodland Hills its name. He had a mansion up in those hills; she'd been there for holiday parties. Serious money in the Valley lived south of Ventura Boulevard, the farther south, the more serious. Sheldon Rosenthal lived a long way south of Ventura.

He made a couple of minutes of small talk while she sipped the delicious coffee, then said, "The analysis you and Mr. Ogarkov prepared of the issues involved in the Butler Ranch project was an excellent piece of work."

There. Now. Nicole armed herself to be polite, as polite as humanly possible. Memories of Indiana childhood, white gloves and patent-leather shoes (white only between Memorial Day and Labor Day, never either before or after), waylaid her for a moment. Out of them, she said in her best company voice, "Thank you very much."

"An excellent piece of work," Rosenthal repeated, as if she hadn't spoken. "On the strength of it, I offered Mr. Ogarkov a partnership in the firm this morning, an offer he has accepted."

"Yes. I know. I saw him downstairs when I was coming in." Nicole wished she hadn't said that; it reminded thefounding partner how late she'd been. Her heart pounded. Now it's my turn. Let me show what I can do, and two years from now Gary will be eating my dust.

Rosenthal's long, skinny face grew longer and skinnier. "Ms. Gunther-Perrin, I very much regret to inform you that only one partnership was available. After consultation with the senior partners, I decided to offer it to Mr. Ogarkov."

Nicole started to say, Thank you. Her tongue had already slipped between her teeth when the words that he had said--the real words, not the words she had expected and rehearsed for--finally sank in. She stared at him. There he sat, calm, cool, machinelike, prosperous. There was not a word in her anywhere. Not a single word.

"I realize this must be a disappointment for you." Sheldon Rosenthal had no trouble talking. Why should he? His career, his life, hadn't just slammed into the side of a mountain and burst into flames. "Do please understand that we are quite satisfied with your performance and happy to retain you in your present salaried position."

Happy to retain you in your salaried position? Like any attorney with two brain cells to rub against each other, Nicole knew that was one of the all-time great lies, right up there with The check is in the mail and Of course I won't come in your mouth, darling. If you weren't on the way up, you were on the way out. She'd thought she was on the way up. Now--

She knew she had to say something. "Could you tell me why you chose Mr. Ogarkov"--formality helped, to some microscopic degree--"instead of me, so that ... so that I'll be in a better position for the next opportunity?" Rosenthal hadn't said anything about the next opportunity. She knew what that meant, too. It was written above the gates of hell. All hope abandon, ye who enter here.

He coughed once, and then again, as if the first time had taken him by surprise. Maybe he hadn't expected her to ask that. After a pause that stretched a little longer than it should have, he said, "The senior partners were of the opinion that, with your other skills being more or less equal, Mr. Ogarkov'svery fluent writing style gives the firm an asset we would do well to retain."

"But--" Nothing Nicole could say would change Sheldon Rosenthal's mind. That was as clear as the crystal decanter that stood on the sideboard in this baronial hall of an office. Nicole could do the mathematics of the firm, better maybe than anybody in it. She was five times the lawyer Gary Ogarkov would ever be-but Gary Ogarkov had ten times the chances. All it took was one little thing. One tiny fluke of nature. A Y chromosome.

They all had it, all the senior partners, every last one of them. Rosenthal, Gallagher, Kaplan, Jeter, Gonzalez & Feng, and most of the junior partners, too. A precise handful of women rounded out the firm, just enough to keep people from raising awkward eyebrows. Not enough to mean anything, not where it counted.

Class action suit? Discrimination suit? Even as she thought of it, she looked into Sheldon Rosenthal's eyes and knew. She could sue till she bankrupted herself, and it wouldn't make the least bit of difference.

Men, she thought, too clear even to be bitter. They would not give a person her due, not if she was female: not as a woman, not as a partner, not as a professional. All they wanted to do was get on top and screw her, in bed or on the job. And they could. All too often, they could. In the United States at the end of the twentieth century, in spite of all the laws, the suits, the cases piled up from the bottom to the top of an enormous and tottering system, they still had the power.

Oh, they paid lip service to equality. They'd hired her, hadn't they? They'd hired half a dozen other peons, and used most of them till they broke or left, the way they were using Nicole. Hypocrites, every last one of them.

"You wished to say something, Ms. Gunther-Pernn?" Rosenthal probably didn't get into court once a year these days, but he knew how to size up a witness.

"I was just wondering"--Nicole chose her words with enormous care--"if you used anything besides the seniorpartners' opinions to decide who would get the partnership."

However careful she was, it wasn't careful enough. Sheldon Rosenthal had been an attorney longer than she'd been alive. He knew what she was driving at. "Oh, yes," he said blandly. "We studied performance assessments and annual evaluations most thoroughly, I assure you. The process is well documented."

If you sue us, you're toast, he meant.

Performance assessments written by men, Nicole thought. Annual evaluations written by men. She knew hers were good. She had no way of knowing what Gary's said. If they were as good as hers ... If they're as good as mine, it's because he's got the old-boy network looking out for him. There's no way he's as good at this as I am.

But if Rosenthal said the process was well documented, you could take it to the bank. And you'd have to be crazy to take it to court.

"Is there anything else?" he asked. Smooth. Capable. Powerful.

"No." Nicole had nothing else to say. She nodded to the man who'd ruined her life--the second man in the past couple of years who'd ruined her life--and left the office. Lucinda watched her go without the slightest show of sympathy. Woman she might be, and woman of color at that, but Lucinda had made her choice and sealed her bargain. She belonged to the system.

The stairway down to the sixth floor seemed to have twisted into an M.C. Escher travesty of itself. Going down felt like slogging uphill through thickening, choking air.

A couple of people she knew stood in the hallway, strategically positioned to congratulate her--news got around fast. But it was the wrong news. One look at her face must have told them the truth. They managed, rather suddenly, to find urgent business elsewhere.

Cyndi's smile lit up the office. It froze as Nicole came in clear sight. "Oh, no!" she said, as honest as ever, and as inept at keeping her thoughts to herself.

"Oh, yes," Nicole said. She almost felt sorry for her secretary.Poor Cyndi, all ready and set to be a partner's assistant, and now she had to know she'd landed in a dead-end job. Just like Nicole. Just like every other woman who'd smacked into the glass ceiling. "They only had one slot open, and they decided to give it to Mr. Ogarkov." She felt, and probably sounded, eerily calm, like someone who'd just been in a car wreck. Walking past Cyndi, she sat down behind her desk and stared at the papers there. She couldn't make them mean anything.

After a couple of minutes, or maybe a week, or an hour, the phone rang. She picked it up. Her voice was flat. "Yes?"

"Mr. Ogarkov wants to talk to you," Cyndi said in her ear. "He sounds upset."

I'll bet, Nicole thought. She could not make herself feel anything. "Tell him," she said, "tell him thanks, but I really don't want to talk to anyone right now. Maybe tomorrow." Cyndi started to say something, but Nicole didn't want to listen, either. Gently, she placed the handset in its cradle.

Copyright © 1999 by Harry Turtledove

Copyright © 1999 by Judith Tarr

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details