Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: valashain

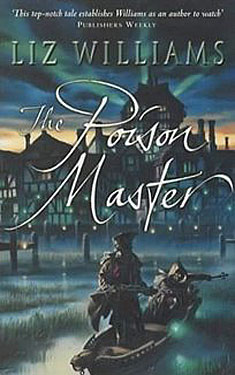

The Poison Master

| Author: | Liz Williams |

| Publisher: |

Tor, 2003 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

On the planet of Latent Emanation, humans are the lowest class, at the mercy of their mysterious alien rulers, the Lords of Night. But Alivet Dee, an alchemist, can't help but question the Lords' rule ever since her twin sister was taken to serve in their palace. Alivet saves every penny to pay her sister's unbonding fee, but her plan is destroyed when one of her potions kills a wealthy client--and Alivet finds herself wanted for murder. Her only hope is the darkly attractive man who may have engineered her downfall but who still offers her a last chance of salvation.

A Poison Master from the planet Hathes, Arieth Mahedi Ghairen needs an alchemist of Alivet's expertise to find the one drug that can take down the Lords--and free the universe from their rule. Sequestered in Ghairen's fortress laboratory, lied to by both her new ally and his daughter's enigmatic governess, Alivet doesn't know whom to trust or where to turn for answers. But driven to undo her sister's fate, Alivet races to hone her skills in time--even as time runs out.

Excerpt

Chapter I

Trinity College, Cambridge - 1547

Are you certain this unnatural device will not fail us?" Sir John Cheke's face was a study in apprehension. Beyond the windows of the college hall, the May twilight grew blue and dim. Cheke reached for a candle and lit it.

"Of course I am certain," Dee replied, swallowing his impatience. "I should not have proposed such a matter to you if I had not been entirely sure of my theorems." He pointed to a complex arrangement of levers, mirrors, and pulleys, concealed behind the pale stone arches.

"Nevertheless, if the theatrical player is actually intended to ride upon this contraption--" Cheke hesitated. "And though I believe you to be a prodigy in mathematics, you are youthful, sir, and prone to eagerness. Will the actor be safe?"

"He will be as safe as if he sat bestride an aged mule upon the Ely road." John Dee took care to maintain a tranquil countenance above his frayed ruff, belying a degree of inner doubt. It had taken several sleepless nights to work out the practical consequences of his plan and Dee was by no means sure that it would prove a success. But how else to test the theory? The expression that Cheke wore now was a familiar one. It had often been seen to steal across his old tutor's features, like cat-ice upon the millponds of the Cam, when Dee had come up with some new notion, but he was also confident that Cheke could be persuaded to support the current proposal. After all, it was well known that Cheke would not set foot out of his house before examining the configuration of the stars, and frequently consulted Dee as to the more pressing astrological portents. Moreover, Cheke and his colleagues had already proved instrumental in encouraging Erasmus' new learning at the University. Arabic arithmetic, which Dee was currently engaged in teaching to a new generation of undergraduates, was now all the rage. So was Greek philosophy and that meant that Greek plays might also be popular, such as Aristophanes' Peace, which Dee was now currently attempting to stage.

Cheke prodded the thing that sat before him with a wary foot.

"But a mechanical beetle? I do wonder, John, at the chambers that your imagination must contain. Even at nineteen you manage to surpass the notions held by men twice your age!"

The beetle, some four feet in length and constructed of wood and metal at a local forge, rocked gently at the touch of Cheke's shoe.

"Take care! And I venture to remark that it is not my imagination," Dee hastened to say, "but that of Aristophanes himself, who was the first to conceive of such a scheme."

"One might suggest that the playwright's interest was allegorical rather than mechanical." Cheke gestured disapprovingly toward the copy of Peace that lay upon a nearby table. "That the hero of this play succeeds in reaching Olympus and the gods on the back of a giant dung beetle, rather than the winged steed of legend, gives Aristophanes license for a number of broad jests and references."

"Broad jests aside, it is the principle that counts."

"Indeed. Explain to me once more how you intend to persuade this monster to part company from the ground?"

"I am beginning work upon an 'art mathematical,' which I term 'thaumaturgy,' " Dee explained. He took a deep breath, willing himself not to launch into an explanation that would cause a glaze to appear across Cheke's eyes. Sometimes it was difficult to remember that other people did not seem to enjoy the same ease with mathematics as Dee himself. Sorting through the muddled pile of notes, he took up a scrap of parchment and began to read. " 'It giveth certain order to make strange works, of the sense to be perceived and of men greatly to be wondered at.' "

"Men will indeed greatly wonder," Cheke remarked acidly, "if a gigantic flying dung beetle should hurtle across the college dining room and flatten the unhappy audience. I want details, sir, not idle speculation such as one may hear in any tavern in the town. How is it going to fly?"

"It is based on the principles explored by the Greek mathematician Archytas. He demonstrated it by means of a wooden dove, which was able to fly unaided," Dee explained. "In Nuremberg, too, an artificer succeeded in constructing an iron fly that soared about the room and returned safely to his hand. And an artificial eagle was also produced, with similar results. I myself have conducted experiments with a metal insect of my own, this time fashioned of bronze, and have achieved a measure of success. However, I am reluctant to do the same with an object of these proportions"--Dee nudged the beetle--"and hence I have arranged this purely mechanical sequence of pulleys, operated by the elements of air and water, which are intended to move the device between the rafters. Both methods involve the application of mathematics and if we are successful in this more material exercise, I will attempt to produce true unaided flight in the beetle itself. Imagine," he went on, "if we could devise a flying machine that could transport a man clear across the country. With the present condition of our English roads, a man could make a fortune with such an engine."

Cheke's round face embodied skepticism. "First things first, John. Let's get the beetle to the lofty peak of the Trinity ceiling before we start to muse about crossing the country."

"A wise plan," Dee agreed. Cheke was the Chancellor, when everything was said and done, and it would not do to be too insistent. He was fortunate that Cheke was allowing him to stage the play at all.

To the detriment of his students, Dee spent the next few days in a haze of mathematical speculation, distracted only by the imploring questions of the leading theatrical player.

"What if I fall off the device?" Will Grey pleaded, kneading his cap between his hands. "Are you certain that this is safe?"

With an inward sigh, Dee gave the same reassurances to Grey that he had previously made to Sir John Cheke.

"All you have to do is to maintain a steady hold upon the scarab's shell. The ropes and pulleys will do the rest of the work. Now, my Trygaeus, be brave, as befits a true hero approaching the Olympian heights!"

"All very well for you to say," Grey muttered. "Since your part is merely to skulk in the wings like a curber's warp."

"Exactly." Dee clapped Grey on the shoulder. "Where I shall be taking good care that everything goes according to plan."

Once the disconsolate actor had gone, Dee went back into his rooms and sat down at the desk. Spring rain streaked the leaded windows, turning the bleached stones of Trinity as gray as bone. An east wind, cold as the forests of Muscovy from which it had come, roared across the fens and rattled the doors. Somewhere in the building Dee could hear the drift of a lute. Footsteps clattered on the wooden staircase, accompanied by a sudden babble of voices. Ignoring these distractions, Dee riffled the parchments that covered the desk until he located the letter that had arrived that morning from Roger Ascham at Louvain. Reading the letter once more, Dee marveled at the prospect of living in such an age as this, when a new discovery seemed to spring forth every day like wisdom from the head of Jupiter . . .

He wondered whether there was any truth in this latest theory. He had come across it before in an account of Rheticius', but now it seemed that someone had published it in a book. It would be worth his while to hunt down a copy of this De Revolutionibus, Dee thought. An intriguing notion: that the Earth journeyed about the sun rather than the other way about, a return to most ancient principles.

Idly, Dee began to speculate and soon became engrossed in the half-visionary, half-mathematical dreaming that had proved the hallmark of his success to date. Despite Cheke's skepticism, he felt sure the principles that had led to the flight of the little bronze bee could be harnessed to lift a much larger object, and he pictured himself soaring above the woods and patchwork fields of England.

In his mind's eye, the Thames lay below, a silver thread snaking toward a glistening sea, and all the roofs and gables of London spread out beneath him like children's toys. It would be akin to the view from the spire of St. Mary's in Cambridge, the highest that Dee had ever stood above a town, yet surely from a greater height everything would look even more remote. Imagination took Dee sailing across London, over the black-and-white whimsy of Nonsuch Palace, over the turrets of Oxford and the green hills of Gloucestershire, as far as the borders of Wales and then up through the rainy skies into the heavens until he could see the Earth itself, hanging like an orb against a field of stars and suns.

It was the very image of an astrolabe: he could almost see the roads traveled by each and every world around the sun. And Dee thought: If only my device could reach the realms of the sublunary spheres. Then I could see for myself the truth of the matter, whether the world travels around the sun, or vice versa . . .

Someone knocked sharply on the door, returning Dee to Earth. It proved to be Cheke, with yet another worry, leaving Dee no more time for interplanetary speculation.

Much to Cheke's surprise, and Dee's secret relief, the rehearsals for the performance of Peace passed with only a few hitches.

"It will all go ill on the night," Cheke said gloomily, when Dee pointed out that this proved the soundness of his calculations. From the wings, Will Grey could be heard vomiting into a bucket, whether with the sensation of the flight itself or relief at having survived it, Dee did not know.

"Nonsense," said Dee. "You must have more faith in mathematics."

Copyright © 2003 by Liz Williams

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details