Added By: Administrator

Last Updated:

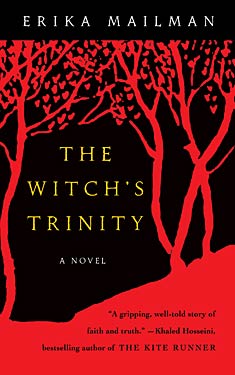

The Witch's Trinity

| Author: | Erika Mailman |

| Publisher: |

Crown Publishers, 2007 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Horror |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

The year is 1507, and severe famine strikes a small town in Germany. A friar arrives from a large city, claiming that the town is under the spell of witches in league with the devil. He brings with him a book called the Malleus Maleficarum--"The Witch's Hammer." It is a guide to gaining confessions of witchcraft. The friar promises he will identify the guilty woman who has brought God's anger upon the town, burn her, and restore bounty.

The elderly Güde Müller suffers stark and frightening visions; none in the village knows this, and Güde herself worries that the sharpness of her mind has begun to fade. Yet of one thing she is absolutely certain: She has become an object of scorn and a burden to her son's wife. In these desperate times, her daughter-in-law would prefer one less hungry mouth at the family table. As the friar turns his eye on each member of the tiny community, Güde dreads what her daughter-in-law might say to win his favor, and that her secret visions will be revealed.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

In the second year of no harvest, 1507 Tierkinddorf, Germany

It was a winter to make bitter all souls. So cold the birds froze midcall and our little fire couldn't keep ice from burrowing into bed with us. The fleas froze in the straw beds, bodies swollen with chilled blood.

We were hungry.

It had been a poor year for grain, like the year before, and the blasted field was now covered with snow. What game there was starved too, their ribs plain as kindling. But soon enough we ate all of those and there were no longer claw marks leading us along their little paths.

The lord's mill, which Jost ran, hadn't been in use for years. When I looked upon the mill wheel a fortnight ago, a cobweb stretched from the hub to the teeth. No one had any grain to grind and so our barter was based on "next harvest." Last year, the lord had released the vassals from obligation and we had all walked the furrows of the tilled earth many times, seeking a scrap thought useless before, even chaff, something to put into our mouths. The soil was as if salted. Seeds went into it only to fester and wither. We did all manner of things to change our fortune. We prayed in the way that the priest asked us to, with the Lord's Prayer, raising our eyes to heaven as we spake of the daily loaf God might grant us. Incense cloyed our throats as we prayed again and again, asking Mary's help as well. We became as gaunt as the saints carved onto the boards of the altar.

And we also did what the priest asked us not to do. Facing to the west, where the sun sets, we slaughtered beasts and poured the blood onto the soil. We dabbed blood into the middle of our palms to represent the harvest we wished to hold. We sang the old songs, our voices hushed so that the ancient music would not drift back to the church. We could not eat the meat of the ritual beasts, and so with tears in our eyes we burned the goats we might have eaten. We watched the smoke drift with the cold wind, incense the earth might prefer to the sweetish cloud from the censer.

We scolded the fields as if they were children; we threw the silt at the sky in a dusty haze and screamed. Künne Himmelmann slept with a clod beneath her pillow.

And nothing changed.

Nothing changed except that snow fell.

My son, Jost, and his wife, Irmeltrud, never spake in jest anymore; never did they laugh. No one did. I felt worst for the young ones. I had already had a lifetime when food was plentiful and neighbors bantered with each other, but they had not known lightness, only heavy, stolid days. I tried now and then to tell funny stories to Alke and Matern, my grandchildren, stories my parents had once told me, of old Lenne kissing her brother by mistake, deep in her cups, or the year the maypole came crashing down and all the girls were cross for thought of the bad luck it brought. But I was the only one who made such effort, and after a time of watching the moveless faces of my family, I ceased myself. Alke and Matern were always solemn. Because they were so thin, they didn't have the strength to race each other into the woods as children should. They played their games close to the fire, and oftentimes their shoulders were joined. I knew they sat that way to keep each other warm.

Alke, the elder, would have no doubt been the prettiest one in the village if only there were color and plumpness to her cheeks. But her blond hair, which should have shone like poppy oil, was lusterless. She had not much spirit to her. In several seasons, she would be marriageable, but would she be able to flirt at Mayfest to gain a lover, as Künne and I had done so shamelessly when we were her age?

And Matern, the boy, was made like a girl by these circumstances. Tears came to his eyes easily and he was hurt by the smallest slight. The idea of him cleaving to a woman and taking care of all the household's needs—hunting and wood getting—seemed an impossibility. Matern would always be helpless, an eternal child created by the absence on the table. And so we all did our best to exist in the same cottage without food, letting the silence fall upon all of us. If my Hensel had been yet here, he'd have made them merry, but he died when Jost was yet a child, turning the world upside down like a plate.

"Mutter, Großmutter has hardly any soup," said Matern, eyeing my bowl.

"Soup's for those who work," said Irmeltrud. "Those who barely move all the day long need little to sustain them." Jost tried to catch her eye, but she wouldn't let him. Such a thing was true, but she was ashamed to have spoken it.

We all sat at the table, backs straight in the formal wish that there might be real food served upon it. Members of my family had sat upon these benches for so many generations, I felt the grooves placed by their more ample bodies. Of course, they had assembled for several meals each day, while we now gathered in the late afternoon for our sole serving.

The soup looked hardly worth the having, coins of carrot floating in water barely flavored with rosemary. The sojourn in the soup pot had likely not softened these rough roots. We had not had meat since Michaelmas. When Irmeltrud turned her back to fill Matern's bowl, Jost poured some of his soup into my mine. "No, son," I said in a low voice. He set his jaw. When Irmeltrud sat down, I saw her notice the sudden difference in my bowl. Her eyes narrowed and I thought, as I often had, how her face expressed the very fume of Eve when she realized the apple had undone all the good. Years ago, Irmeltrud used to smile at me, thinking that earning Jost's favor required mine. She asked my advice in all things and was hesitant as a midafternoon spider. As soon as the marriage banns were read, however, a sourness crept into her face and she has been so with me ever since.

We all held hands while Jost said the prayer of thanks. Alke's fingers were impatient in my right hand, while my left stretched across the table to capture Matern's. And then we all picked up our spoons and wetted our tongues.

At least it was hot.

Heat added flavor to things that had none, we had learned.

I took a spoonful into my mouth and simply sat with it, one carrot coin sitting on my tongue like a communion crumb. I closed my eyes to fully sense it, the meager gift of water with

a ghost of taste. Everyone else plunged in with quick spoons, as if it would wink at them and run out the door if they did not hurry.

"What has Ramwold said this day?" asked Irmeltrud, in between gulps. Jost and the other village men had gone to hear him read the runes.

"He said the winter is yet to stretch more grievous," said Jost. Some Suppe dribbled from his mouth from the haste. He used no cloth to wipe his face, only his own tongue, to not waste even a drop.

"Can it be so?" asked Irmeltrud in a horrified tone. "What have we done to bring this?"

"I know not, but there is talk of a hunting party to gather together. The woods here are emptied."

"Better to solve the reason for our hunger than to lose yourselves to a boar's horns or worse betides. The woods are full of the devil's minions."

"Solve it, Mutter? How?" asked Matern with wide eyes.

"By seeking the source of the evil and suppressing it," said Irmeltrud. She had already reached the bottom of her bowl, despite her talking, and clapped it down on the board. Her eyes snaked over to mine. "Someone is making mischief and bringing misery to this village," she said. "One who has made a bargain with the devil and benefits from our distress."

"We all toil in sin," said Jost. "Yet I know of no one who would have struck such a bargain."

"Not all toil," she said, and looked into my eyes. I saw no warmth there. "There's talk of old Künne Himmelmann."

"What manner of talk?" Jost's voice took on an edge of anger.

"The Töpfers say their hen has stopped laying. She is simply dried of eggs. And this happened after Künne sat down on a rock by their door."

"Everyone sits at that rock," said Jost. "The children sit there to play, the women sit on that rock to card their wool. And an old one such as Künne, to be walking the road, she'd have to tarry a bit to rest her feet."

"But the hen?"

"The hen is as hungry as the rest of us and hasn't the will to push out eggs," said Jost.

I stared down at the rind of carrot spinning slowly in my bowl. Künne was my friend. I remembered when her hair had been flaxen, her braids thick as a goose neck. Now they were thin and gray, straggled like mine. I had taken only one sip from the bowl but could eat no more. If Künne was being talked of in this way, she was in danger. A Dominican friar had come to our village a week ago—he had been the one to speak of God punishing one of our villagers by withholding the harvest from everyone. I nodded to Jost and began to push my bowl across the board to him. He smiled weakly, knowing what Künne was to me. My shaky fingers, barely recognizable to me now as those that once easily did my bidding, pushed too hard and the bowl spilled.

"Fool!" said Irmeltrud as she stood and tried to scoop the liquid back into the bowl. "You've wasted an entire bowl. Would that you worked for it yourself, you'd treat it a little more carefully!"

It was true. I'd done naught to prepare for this repast. My fingers were too shaky for the knife to cut the carrots and my frame too frail to carry water to the cauldron.

The soup dripped down onto the dirt below. Jost's face registered the regret that he had...

Copyright © 2007 by Erika Mailman

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details