Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: valashain

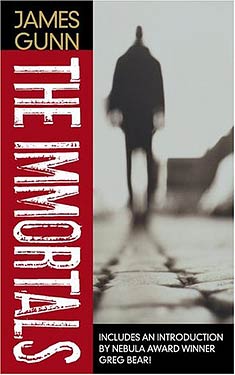

The Immortals

| Author: | James E. Gunn |

| Publisher: |

Bantam Dell Publishing Group, 1970 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Immortality Apocalyptic/Post-Apocalyptic Near-Future |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

WHAT IS THE PRICE OF IMMORTALITY?

For nomad Marshall Cartwright, the price is knowing that he will never grow old. That he will never contract a disease, an infection, or even a cold. That because he will never die, he must surrender the right to live.

For Dr. Russell Pearce, the price is eternal suspicion. He appreciates what synthesizing the elixir vitae from the Immortal's genetic makeup could mean for humankind. He also fears what will happen should Cartwright's miraculous blood fall into the wrong hands.

For the wealthy and powerful, no price is too great. Immortality is now a fact rather than a dream. But the only way to achieve it is to own it exclusively. And that means hunting down and caging the elusive Cartwright, or one of his offspring.

The Immortals, James Gunn's masterpiece about a human fountain of youth, collects the author's classic short stories that ran in elite science-fiction magazines throughout the 1950s. All-new material accompanies this updated edition, including an introduction from renowned science-fiction writer Greg Bear, a preface from Gunn himself, and "Elixir," Gunn's new short story that introduced Dr. Pearce to another Immortal in the May 2004 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Factmagazine.

Excerpt

Chapter I

The young man was stretched out flat in a reclining hospital chair, his bare left arm muscular and brown on the table beside him. The wide, flat band of the sphygmomanometer was tight around his bicep, and the inside of his elbow, where the veins were blue traceries, had been swabbed with alcohol and betadine.

His eyes followed the quick efficiency of the phlebotomist. Her movements were as crisp as her white uniform.

She opened the left-hand door of the big refrigerator and from the second shelf removed a double plastic bag connected by plastic tubing. There was a hole at the bottom for hanging the bags from an IV pole. The plastic bag was empty, flat, and wrinkled. A syringe needle on a length of clear, plastic tubing was attached.

The technician removed the protective plastic cap from the needle and stretched out the tubing. She inspected the donor's inside arm where it had been sterilized and deadened with lidocaine. The vein was big and soft, and she slipped the needle into it with practiced skill. Dark red blood raced through the tube and into one of the plastic bags. Slowly a pool gathered at the bottom and the wrinkles began to smooth.

The technician stripped a printed label with the date and a number from a sheet of nonstick paper and pressed it on the plastic bag. At the bottom she put her initials.

"Keep making a fist," she said, glancing at the bag.

When the bag was full, she closed a clamp on the tube and removed the needle from the donor's arm, replacing it with a cotton ball and a plastic bandage.

"Keep that on for an hour or so," she said.

She drained the blood in the tubing into test tubes, sealed them, and applied smaller labels on them from the same preprinted sheet of paper before she placed them on a rack in the refrigerator.

The tubing and needle were carefully discarded in a waste disposal canister with a plastic lining.

"The typing will be done at the center," the technician said. "If you're really O-neg, you might make a bit of money from time to time. That's the only kind that we have to buy when we can't get enough donations."

The donor's youthful lips twisted at the corners.

"I'll need your name and address for the records," the technician said briskly, turning to the computer on her desk and typing a number into it. After the young man had given it and she had typed it in, she said, "We can have you notified when the results come back. The lab checks for AIDS, hepatitis, venereal and other blood-carried diseases. All confidential, of course. If you like, we can put your name in our professional donor's file."

Without hesitation the young man shook his head.

The technician shrugged and handed him a slip of paper. "Thanks anyway. Stay seated in the waiting room for ten minutes. There's some orange juice, coffee, and muffins that you can have while you wait. The paper is a voucher for fifty dollars. You can cash it at the cashier's office -- by the front door as you go out."

For a moment after the young man's broad back had disappeared from the doorway, the technician stared after him. Then she shrugged again, turned, and put the unit of blood onto the refrigerator's top left-hand shelf.

A unit of whole blood -- new life in a plastic bag for someone who might die without it. Within a few days the white cells will begin to die, the blood will decline in ability to clot. With the aid of refrigeration, the red cells will last -- some of them -- for three weeks. After that the blood will be sent to the separator for the plasma, if it has not already been separated for packed red blood cells, or sold to a commercial company for separation of some of the plasma's more than seventy proteins, the serum albumin, the gamma globulins....

A unit of blood -- market price: $50. After the required tests, it will be moved to the second shelf from the top, right-hand side of the refrigerator, with the other units of O-type blood. But this blood was special. It had everything other blood had, and something extra that made it unique. There had never been any blood quite like it.

Fifty dollars? How much is life worth?

The old man was eighty years old. His body was limp on the hard hospital bed. The air-conditioning was so muffled that the harsh unevenness of his breathing was loud. The only movement in the intensive care unit was the spasmodic rise and fall of the sheet that covered the old body.

He was living -- barely. He had used up his allotted three-score years and ten, and then some. It wasn't merely that he was dying -- everyone is. With him, it was imminent.

Dr. Russell Pearce held one bony wrist in his firm, young right hand and looked at the monitors checking blood pressure, heart function, pulse, oxygen level....Pearce's face was serious, his dark eyes steady, his pale skin well molded over strong bones.

The old man's face was yellow over a grayish blue, the color of death. The wrinkled skin was pulled back like a mask for the skull. Once he might have been handsome; now his eyes were sunken, the closed eyelids dark over them, his mouth was a dark line, and his nose was a thin, arching beak.

There is a kinship in old age, just as there is a kinship in infancy. Between the two, men differ, but at the extremes they are much the same.

Pearce had seen old men in the nursing units, Medicaid patients most of them, picked up on the North Side when they didn't wake up in their cardboard boxes or Dumpsters, filthy, alcohol or drug addicts many of them. The only differences with this man were a little care and a few billion dollars. Where this man's hair was groomed and snow-white, the other's was yellowish-gray, long, scraggly on seamed, thin necks. Where this man's skin was scrubbed and immaculate, the other's had dirt in the wrinkles, sores in the crevices.

Gently Pearce laid the arm down beside the body and slowly stripped back the sheet. The differences were minor. In dying, people are much the same. Once this old man had been tall, strong, vital. Now the thin body was emaciated; the rib cage struggled through the skin, fluttered. The old veins stood out, knotted, ropy, blue, varicose, on the sticklike legs.

"Pneumonia?" Dr. Easter asked with professional interest. He was an older man, his hair gray at the temples, his appearance distinguished, calm.

"Not yet. Malnutrition. You'd think he'd eat more, get better care. Money is supposed to take care of itself."

"It doesn't follow. As his personal physician, I've learned that you don't order around a billion dollars."

"Anemia," Pearce went on. "Bleeding from a duodenal ulcer, I'd guess. We could operate, but I'm not sure he'd survive. Pulse weak, rapid. Blood pressure low. Arteriosclerosis and all the damage that entails."

Beside him a nurse made marks on a chart. Her face was smooth and young; the skin glowed with health.

"Let's have a blood count," Pearce said to her briskly. "Urinalysis. Type and cross-match two units of blood, packed RBCs if you can get them, and administer one unit when available."

"Transfusion?" Easter asked.

"It may provide temporary help. If it helps enough, we'll give him more, maybe strengthen him enough for the operation."

"But he's dying." It was almost a question.

"Sure. We all are." Pearce smiled grimly. "Our business is to postpone it as long as we can."

A few moments later, when Pearce opened the door and stepped into the hall, Dr. Easter was talking earnestly to a tall, blond, broad-shouldered man in an expensively cut business suit. The man was about Easter's age, somewhere between forty-five and fifty. The face was strange: It didn't match the body. There was a thin, predatory look to its slate-gray eyes.

The man's name was Carl Jansen. He was personal secretary to the old man who was dying inside the room. Dr. Easter performed the introductions, and the men shook hands. Pearce reflected that the term personal secretary might cover a multitude of duties.

"Doctor Pearce, I'll only ask you one question," Jansen said in a voice as flat and cold as his eyes. "Is Mister Weaver going to die?"

"Of course he is," Pearce answered. "None of us escapes. If you mean is he going to die within the next few days, I'd say yes -- if I had to answer yes or no."

"What's wrong with him?" Jansen asked. His tone sounded suspicious, but that was true of everything he said.

"He's outlived his body. Like a machine, it's worn out, falling to pieces, one part failing after another."

"His father lived to be ninety-one, his mother ninety-six."

Pearce looked at Jansen steadily, unblinking. "They didn't accumulate several billion dollars. We live in an age that has almost conquered disease, but its pace has inflicted a price. The stress and strain of modern life tear us apart. Every billion Weaver made cost him five years of living."

"What are you going to do -- just let him die?"

Pearce's eyes were just as cold as Jansen's. "As soon as possible we'll give him a transfusion. Does he have any relatives, close friends?"

"There's no one closer than me."

"We'll need two pints of blood for every pint we give Weaver. Arrange it."

"Mister Weaver will pay for whatever he uses."

"He'll replace it if possible. That's the hospital rule."

Jansen's eyes dropped. "There'll be plenty of volunteers from the office."

When Pearce was beyond the range of his low, penetrating voice, Jansen said, "Can't we get somebody else? I don't like him."

"That's because he's harder than you are," Easter said. "He'd be a good match for the old man when he was in his prime."

"He's too young."

"That's why he's good. The best geriatrician in the Middle West. He can be detached, objective. All doctors need a touch of ruthlessness. Pearce needs more than most; he loses every patient sooner or later. He's got it." Easter looked at Jansen and smiled ruthfully. "When men reach our age, they start getting soft.

Copyright © 1970 by James E. Gunn

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details