Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

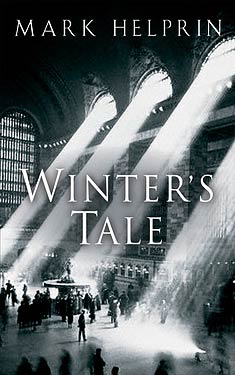

Winter's Tale

| Author: | Mark Helprin |

| Publisher: |

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Magical Realism Urban Fantasy Mythic Fiction (Fantasy) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Film & Television Adaptations

Synopsis

New York City is subsumed in arctic winds, dark nights, and white lights, its life unfolds, for it is an extraordinary hive of the imagination, the greatest house ever built, and nothing exists that can check its vitality. One night in winter, Peter Lake--orphan and master-mechanic, attempts to rob a fortress-like mansion on the Upper West Side.

Though he thinks the house is empty, the daughter of the house is home. Thus begins the love between Peter Lake, a middle-aged Irish burglar, and Beverly Penn, a young girl, who is dying.

Peter Lake, a simple, uneducated man, because of a love that, at first he does not fully understand, is driven to stop time and bring back the dead. His great struggle, in a city ever alight with its own energy and beseiged by unprecedented winters, is one of the most beautiful and extraordinary stories of American literature.

Excerpt

A WHITE HORSE ESCAPES

THERE WAS a white horse, on a quiet winter morning when snow covered the streets gently and was not deep, and the sky was swept with vibrant stars, except in the east, where dawn was beginning in a light blue flood. The air was motionless, but would soon start to move as the sun came up and winds from Canada came charging down the Hudson.

The horse had escaped from his master's small clapboard stable in Brooklyn. He trotted alone over the carriage road of the Williamsburg Bridge, before the light, while the toll keeper was sleeping by his stove and many stars were still blazing above the city. Fresh snow on the bridge muffled his hoofbeats, and he sometimes turned his head and looked behind him to see if he was being followed. He was warm from his own effort and he breathed steadily, having loped four or five miles through the dead of Brooklyn past silent churches and shuttered stores. Far to the south, in the black, ice-choked waters of the Narrows, a sparkling light marked the ferry on its way to Manhattan, where only market men were up, waiting for the fishing boats to glide down through Hell Gate and the night.

The horse was crazy, but, still, he was able to worry about what he had done. He knew that shortly his master and mistress would arise and light the fire. Utterly humiliated, the cat would be tossed out the kitchen door, to fly backward into a snow-covered sawdust pile. The scent of blueberries and hot batter would mix with the sweet smell of a pine fire, and not too long afterward his master would stride across the yard to the stable to feed him and hitch him up to the milk wagon. But he would not be there.

This was a good joke, this defiance which made his heart beat in terror, for he was sure his master would soon be after him. Though he realized that he might be subject to a painful beating, he sensed that the master was amused, pleased, and touched by rebellion as often as not-if it were in the proper form and done well, courageously. A shapeless, coarse revolt (such as kicking down the stable door) would occasion the whip. But not even then would the master always use it, because he prized a spirited animal, and he knew of and was grateful for the mysterious intelligence of this white horse, an intelligence that even he could not ignore except at his peril and to his sadness. Besides, he loved the horse and did not really mind the chase through Manhattan (where the horse always went), since it afforded him the chance to enlist old friends in the search, and the opportunity of visiting a great number of saloons where he would inquire, over a beer or two, if anyone had seen his enormous and beautiful white stallion rambling about in the nude, without bit, bridle, or blanket.

The horse could not do without Manhattan. It drew him like a magnet, like a vacuum, like oats, or a mare, or an open, never-ending, tree-lined toad. He came off the bridge ramp and stopped short. A thousand streets lay before him, silent but for the sound of the gemlike wind. Driven with snow, white, and empty, they were a maze for his delight as the newly arisen wind whistled across still untouched drifts and rills. He passed empty theaters, countinghouses, and forested wharves where the snow-lined spars looked like long black groves of pine. He passed dark factories and deserted parks, and rows of little houses where wood just fired filled the air with sweet reassurance. He passed the frightening common cellars full of ragpickers and men without limbs. The door of a market bar was flung open momentarily for a torrent of boiling water that splashed all over the street in a cloud of steam. He passed (and shied from) dead men lying in the round ragged coffins of their own frozen bodies. Sleds and wagons began to radiate from the markets, alive with the pull of their stocky dray horses, racing up the main streets, ringing bells. But he kept away from the markets, because there it was noontime even at dawn, and he followed the silent tributaries of the main streets, passing the exposed steelwork of buildings in the intermission of feverish construction. And he was seldom out of sight of the new bridges, which had married beautiful womanly Brooklyn to her rich uncle, Manhattan; had put the city's hand out to the country; and were the end of the past because they spanned not only distance and deep water but dreams and time.

The tail of the white horse swished back and forth as he trotted briskly down empty avenues and boulevards. He moved like a dancer, which is not surprising: a horse is a beautiful animal, but it is perhaps most remarkable because it moves as if it always hears music. With a certainty that perplexed him, the white horse moved south toward the Battery, which was visible down a long narrow street as a whitened field that was crossed by the long shadows of tall trees. By the Battery itself, the harbor took color with the new light, rocking in layers of green, silver, and blue. At the end of this polar rainbow, on the horizon, was a mass of white-the foil into which the entire city had been set-that was beginning to turn gold with the rising sun. The pale gold agitated in ascending waves of heat and refraction until it seemed to be a place of a thousand cities, or the border of heaven. The horse stopped to stare, his eyes filled with golden light. Steam issued from his nostrils as he stood in contemplation of the impossible and alluring distance. He stayed in the street as if he were a statue, while the gold strengthened and boiled before him in a bed of blue. It seemed to be a perfect place, and he determined to go there.

He started forward but soon found that the street was blocked by a massy iron gate that closed off the Battery. He doubled back and went another way, only to find another gate of exactly the same design. Trying many streets, he came to many heavy gates, none of which was open. While he was stuck in this labyrinth, the gold grew in intensity and seemed to cover half the world. The empty white field was surely a way to that other, perfect world, and, though he had no idea of how he would cross the water, the horse wanted the Battery as if he had been born for it. He galloped desperately along the approachways, through the alleys, and over the snow-covered greens, always with an eye to the deepening gold.

At the end of what seemed to be the last street leading to the open, he found yet another gate, locked with a simple latch. He was breathing hard, and the condensed breath rose around his face as he stared through the bars. That was it: he would never step onto the Battery, there somehow to launch himself over the blue and green ribbons of water, toward the golden clouds. He was just about to turn and retrace his steps through the city, perhaps to find the bridge again and the way back to Brooklyn, when, in the silence that made his own breathing seem like the breaking of distant surf, he heard a great many footsteps.

At first they were faint, but they continued until they began to pound harder and harder and he could feel a slight trembling in the ground, as if another horse were going by. But this was no horse, these were men, who suddenly exploded into view. Through the black iron gate, he saw them running across the Battery. They took long high steps, because the wind had drifted the snow almost up to their knees. Though they ran with all their strength, they ran in slow motion. It took them a long time to get to the center of the field, and when they did the horse could see that one man was in front and that the others, perhaps a dozen, chased him. The man being chased breathed heavily, and would sometimes drive ahead in deliberate bursts of speed. Sometimes he fell and bolted right back up, casting himself forward. They, too, fell at times, and got up more slowly. Soon this spread them out in a ragged line. They waved their arms and shouted. He, on the other hand, was perfectly silent, and he seemed almost stiff in his running, except when he leapt snowbanks or low rails and spread his arms like wings.

As the man got closer, the horse took a liking to him. He moved well, though not like a horse or a dancer or someone who always hears music, but with spirit. What was happening appeared to be, solely because of the way that this man moved, more profound than a simple chase across the snow. Nonetheless, they gained on him. It was difficult to understand how, since they were dressed in heavy coats and bowler hats, and he was hatless in a scarf and winter jacket. He had winter boots, and they had low street shoes which had undoubtedly filled with numbing snow. But they were just as fast or faster than he was, they were good at it, and they seemed to have had much practice.

Copyright © 1983 by Mark Helprin

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details