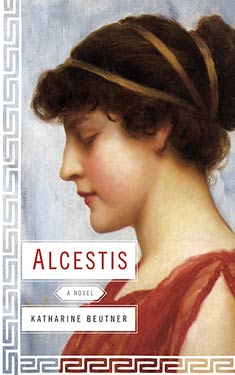

Alcestis

| Author: | Katharine Beutner |

| Publisher: |

Soho Press, 2010 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

In Greek myth, Alcestis is known as the ideal wife; she loved her husband so much that she died and went to the underworld in his place. In this vividly-imagined debut, Katharine Beutner gives voice to the woman behind the ideal and reveals the part of the story that's never been told: What happened to Alcestis in the three days she spent in the underworld?

Excerpt

Prologue

They knew the child's name only because her mother died cursing it, clutching at the bloodied bedclothes and spitting out the word as if it tasted sour on her tongue. After a few minutes her tongue stilled, and her limbs too, until she lay on the bed gray and cold as stone. The servants stood around the bed in a rough circle, looking down at the tangled mess the queen had made and thinking of the rituals her death would require, the sacrifices, the burning herbs nailed in clusters to the mud-brick walls. The room smelled of copper and sweat, as if a great battle had been fought within it. Anaxibia had warred with death and lost; for the moment, at least, her baby daughter had won.

They'd wiped the babe off, tied the cord, and swaddled her in a blanket. She squalled at first, face purple with incoherent rage, but then she lay quietly in her cradle as her mother's body hardened and cooled. She knew nothing of death. She came into the world as any girl might, unexpected, tolerated. If she hadn't been a royal child, she might have been left alone on a hillside to die nameless beneath the summer sun. As it was, Pelias had no time for the naming of girl children. The king would abandon the palace after hearing of his wife's death, taking a group of his best fighting men to hunt boar for the funeral feast, and would not return until the morning of her burial day. For two days the palace would be empty except for the children and the servants and the slaves and the animals and the body of the dead queen, swelling in the heat. The queen's spirit had already departed, trailing after the god Hermes like a cloak in the dust. The god had looked down at the baby in her cradle, a long silent look, but she had not seen him—or if she had, she had not cried at the sight.

But now the baby wriggled, bleated like a lamb. The queen's body servant sighed and wiped her bloody hands on her shift. Stirred out of reverie, the other women shook their heads and blinked in the low light.

The women leaned down and rolled Anaxibia's body over so they could strip the linens from the bed. The queen lay slumped on her side, her brown braids mussed and tangled, her face smooth. She was twenty-four years old. The baby girl in the cradle was her fifth child, and the other children had been waiting for hours, clustered outside the bedchamber, to see their mother and new sibling. Their thin voices slipped into the room beneath the closed door. The women looked at each other. "Go on," said the head maid, nodding to two of the others. "They must be told. And the king too."

The chosen messengers left. After a moment, the children began to wail outside the door, their cries fading as the maids hurried them out of the women's quarters. The head maid turned back to the dead queen, then looked at the serious faces of the two other serving women who'd stayed behind, looked over at the baby in the cradle. She bent down to pick up the child and balanced the baby's small damp head against her shoulder. "Alcestis," she said and looked to the others for confirmation. "That what you heard too?"

Dry-eyed and solemn, they nodded. They'd seen this bloody struggle too often to weep. "Alcestis," said Anaxibia's body servant, and looked at the baby, who had fallen asleep in the head maid's arms. "Poor thing."

The head maid put the baby down on her back in the crib. She sent a servant to fetch the kitchen maid who'd just borne a son, sent another to call the men to bring oils and cloths. The wet nurse took some time to arrive, but Alcestis did not cry. She lay in the cradle and listened to the skim and slap of the women's hands spreading oil on her mother's flesh, the silky whispers as they combed out and re-braided her mother's hair. She breathed in the smell of the room, the bodily stench of failed combat with the gods, the reek of a thread snipped. The women watched the baby with nervous eyes as they worked. The two who lived to hear of Alcestis's death—if one could call it death—would recall her birth, then, and mutter to each other about the way the girl had opened her tiny mouth to suck in the fouled air as if it could replace her mother's milk. Perhaps she'd grown used to death then, they'd say. Perhaps she'd been hungry for it all her life.

I don't remember those moments, those sounds, those smells. But this is what I imagine from what I was told as I grew older. This, said the maids, the servants, my sisters—this was how your story began.

Copyright © 2010 by Katharine Beutner

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details