Added By: Weesam

Last Updated: illegible_scribble

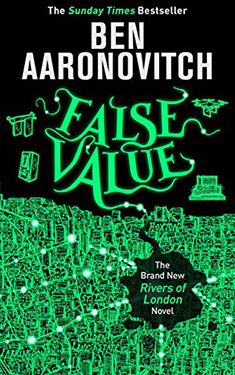

False Value

| Author: | Ben Aaronovitch |

| Publisher: |

Gollancz, 2020 DAW Books, 2020 |

| Series: | Rivers of London: Book 8 |

|

0. The Furthest Station |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Contemporary Fantasy Comic Fantasy Urban Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Peter Grant is facing fatherhood, and an uncertain future, with equal amounts of panic and enthusiasm. Rather than sit around, he takes a job with émigré Silicon Valley tech genius Terrence Skinner's brand new London start up - the Serious Cybernetics Company.

Drawn into the orbit of Old Street's famous 'silicon roundabout', Peter must learn how to blend in with people who are both civilians and geekier than he is. Compared to his last job, Peter thinks it should be a doddle. But magic is not finished with Mama Grant's favourite son.

Because Terrence Skinner has a secret hidden in the bowels of the SCC, a technology that stretches back to Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, and forward to the future of artificial intelligence. A secret that is just as magical as it is technological - and just as dangerous.

Excerpt

Chapter One

January: Some Swans are White

My final interview at the Serious Cybernetics Corporation was with the company's head of security himself - Tyrel Johnson. Mid-fifties, one of those big men who by dint of clean living and regular exercise have failed to go to fat and instead compacted down to the tensile strength of teak. Light-skinned, with short grey hair and dressed in a bespoke navy pinstripe suit with a lemon cotton shirt and no tie.

Since everybody else in the building dressed in varying degrees of slacker-casual, wearing a suit made a statement - I was glad I'd worn mine.

Judging by the pastel-coloured walls, the spindly stainless-steel furniture and the words Ask me about my poetry painted along one wall in MS Comic Sans, I was guessing that Mr Johnson hadn't decorated his office himself.

I was stuck on the low-slung banana-yellow sofa while he was perched on the edge of his desk - arms folded. Working without notes, I noticed.

'Peter Grant.' He spoke with a West Indian accent, apparently Trinidadian although I can't tell them apart. 'Twenty-eight years old, Londoner, plenty of GCSEs, three C-grade A levels but you didn't go on to further education, worked for Tesco, a couple of small retailers, something called Spinnaker Office Services - what was that?'

'Office cleaning.'

'So you know your way around a mop?' He smiled.

'Unfortunately,' I said, manfully resisting the urge to add 'sir' to the end of every sentence. Tyrel Johnson had stopped being a copper the year I was born, but obviously there were some things that never leave you.

I realised that I might have to come to terms with that myself.

'Two years as a PCSO... then you joined the Metropolitan Police and managed a whole six years before leaving.' He nodded as if this made perfect sense to him - I wish it did to me.

'Following probation you went into Specialist, Organised and Economic Crime Command,' said Johnson. 'Doing what exactly?'

It had been agreed that it would be counterproductive all round if I was to mention the Special Assessment Unit, otherwise known as 'The Folly', also known as 'Oh God, not them'. That there was a section of the Met that dealt with weird shit was quite widely known within the police; that it had officers who were trained in magic was not exactly a secret, but definitely some- thing nobody wanted to talk about. Especially at a job interview.

'Operation Fairground,' I said.

'Never heard of it.'

'Nigerian counterfeiting gangs.'

'Undercover?'

'No,' I said. 'Interviews, statements, follow-ups - you know - leg work.'

'Why don't we just get down to the main event?' said Johnson. 'Why did you leave the police?'

Being ex-job, Johnson was bound to still have contacts in the Met - he would have checked my name out as soon as my CV was shortlisted. Still, the fact that I was even having this interview indicated that he didn't know everything.

'There was a death in custody,' I said. 'I was put on suspension.'

He leaned forward slightly for emphasis.

'Tell me, son,' he said. 'Were you responsible?' I looked him in the eyes.

'I should have seen it coming, and I didn't act fast enough to stop it,' I said - it's so much easier to lie when you're telling the truth.

He nodded.

'There always has to be someone to blame,' he said. 'You didn't try to stick it out?'

'I was encouraged to move on,' I said. 'Somebody had to go, but they didn't want a fuss.' I didn't say who 'they' were, but that didn't seem to bother Johnson, who nodded sagely.

'What do you think about computers?' he asked, showing that the interview trick of suddenly changing the subject was also something that never leaves you when you exit the Job.

It's always 'the Job', with a capital letter, as if once you're in it you can't imagine doing anything else.

Just be yourself, Beverley had said when I was dressing that morning.

'I once played Red Dead Redemption for twenty-four hours solid,' I said.

Johnson's eyes narrowed, but there was amusement in the set of his mouth. It faded a little.

'I'll be honest with you, son. All things being equal you'd normally be a bit overqualified for this job,' he said. 'But I have a problem.'

'Sir?' I tried to keep an expression of bland interest on my face.

'Someone in the workforce is up to no good,' he said, and I relaxed. 'I can feel them scuttling around like a rat. I don't have the time to chase them so what I need is a rat-catcher, someone I can trust to do the job properly.'

'I worked Oxford Street,' I said. 'Rat-catching's my speciality.'

'Yes,' he said slowly. 'You'll do - when can you start?'

'Right now,' I said.

'Chance would be a fine thing,' said Johnson. 'We have to navigate you through HR first, so Monday will be fine. Nice and early.'

He straightened up off his desk and I jumped to my feet. He held out his hand - it was like shaking hands with a tree.

'Just so we're clear,' he said, not letting go of my hand. 'No matter what anyone else thinks - including the Uber-hobbit himself - you work for me and only me. Understand?'

'Yes, sir,' I said.

'Good,' he said and walked me out of the building.

*

Johnson had made a point of calling the human resources department 'HR' rather than its official internal company name, the Magrathean Ape-Descended Life Form Utilisation Service, just as he called the department I had just joined 'Security' rather than the Vogon Enforcement Arm.

That, and the fact that employees were officially referred to as 'mice', didn't stop the Magrathean Ape- Descended Life Form Utilisation Service sending me a twelve-page contract by email and snail-mail and a non-disclosure agreement that was worse than the Official Secrets Act. My mum warned me that the company didn't have a very good reputation amongst cleaning staff.

'Den hat for deal witt ein den nor dae pay betteh,' she told me.

Den nor dae pay betteh was Mum-speak for below minimum wage.

My mum also wanted to know whether I was attending pre-natal classes with Beverley and making sure she ate properly. Eating properly by Mum's definition meant Beverley consuming her own weight in rice every day so I lied and said she was. When I asked Beverley about any cravings, she told me not so far.

'I can pretend,' she said just after Christmas. 'If it makes you feel better.'

Beverley Brook lived south of Wimbledon Common, in both sides of a semi on, appropriately enough, Beverley Avenue. The walls between the two halves had been knocked through and the rooms converted, but you could still feel the ghosts of the right-hand kitchen in the way the floor texture changed under your feet when you moved around the master bedroom's en suite bathroom. There had been a few changes since I moved in permanently, mostly involving storage space and encouraging Beverley to use it for her clothes - with mixed results.

We slept on the ground floor because Beverley was the goddess of the river Beverley Brook, which ran along the bottom of her garden, and she liked to have swift access to her watercourse in times of need.

Beverley was five months gone by then - an event marked by her borrowing a slightly larger wetsuit from one of her sisters to accommodate the bump. She'd also taken to working on her dissertation, 'The Environmental Benefits of Waterway Reversion', while sitting in a straight-backed chair at the kitchen table.

That evening I sat at the other end and went through the contract, most of which seemed to be concerned with detailing the many and varied ways the Serious Cybernetics Corporation could fire me without compensation. It was hard work, and I kept on being distracted by the beauty of Beverley's eyes as they flicked from laptop screen to notebook, and her slim brown fingers as they held a highlighter pen poised over the textbooks open in front of her.

'What?' she asked, looking up at me. 'Nothing,' I said.

'Okay,' she said, and I watched as she bent to check something in one of the books and her locks fell over her shoulders to reveal the smooth curve of the back of her neck.

'Stop staring at me,' said Beverley without looking up. 'And get on with your contract.'

I sighed and went back to decrypting the fact that not only was I to be on a twelve-month probation, but that the management reserved the right to extend that probation indefinitely if I failed to meet a series of loosely defined performance criteria. It was all very depressing, and borderline legal, but it wasn't as if I had any choice. I hadn't had a job, as opposed to 'the Job', for over eight years. The last being a stint stacking shelves in the Stockwell Kwiksave which had ended when the company went bust. The best that can be said about shelf stacking is that it's not working as a cleaner.

I signed the contract in the indicated boxes and stuck it back in the envelope provided.

Parking being what it was around Old Street roundabout, there was no way I was going to drive from Bev's. Instead I got the 57 from Holland Avenue and hit the Northern Line at South Wimbledon, where I squeezed myself into an imaginary gap between two large white men. A morning commute on the Northern Line is frequently grim but that morning the atmosphere was strange and I swear I felt a tingle of vestigium. Nothing professionally worrying, just a whiff of glitter and stardust. A middle-aged woman a couple of armpits down the carriage from me said, 'It's a godawful small affair,' and burst into tears. As the train pulled out I thought I heard a man's voice say, 'To the girl with the mousy hair,' but the noise of the train drowned it out. By the time we got to Colliers Wood, nobody was singing but

I'd picked up enough of a nearby conversation to learn that David Bowie was dead.

In case I hadn't twigged that the Man Who Fell to Earth was brown bread, the newly mounted poster facing out through the glass windows of the SCC's main entrance, and the teenaged intern handing out black armbands to all the arriving mice, would have been a clue.

The poster was of Bowie in his Ziggy Stardust phase with a red lightning bolt running across his face, and had been placed just under the large friendly letters that spelt out don't panic across the window.

At no point did anyone suggest that wearing an arm-band was compulsory, but I noticed that none of the mice, not even the ones in death metal sweatshirts, refused one.

The Serious Cybernetics Corporation's atrium was fitted with a line of card-activated entrance gates. Unlike most corporate offices, the barriers here were head-high and made of bullet-resistant Perspex - a level of security I'd only ever seen at New Scotland Yard and the Em- press State Building. Every mouse had an RfiD chip built into their brightly coloured ID card and had to tap in at the barrier. Three whole paragraphs of my employ- ment contract detailed exactly what penalties I would suffer should I lose or allow someone else to use my card. Since I hadn't actually received one yet, I dutifully reported to the long bright blue reception desk, where a young and incredibly skinny white woman with an Eastern European accent smiled at me and handed me my brand-new ID card and lanyard.

Then she handed me a towel.

It was a fluffy orange bathroom towel. 'What's this?' I asked.

'It's your first day towel,' said the receptionist. 'You wrap it around your head.'

'You're joking?'

'It shows you're a newbie,' she said. 'Then everyone will know to be friendly.'

I gave the towel a cautious sniff - it was clean and fluffy and smelt of fabric conditioner.

'Can I keep the towel afterwards?' 'Of course.'

I wrapped the towel around my head and fastened it like a turban. 'How do I look?'

The receptionist nodded her head. 'Very nice,' she said.

I asked how long I was supposed to keep it on, and she told me the whole first day.

'Well, at least it will muffle the tracking device,' I said, but that just got me a blank look.

Past the barriers was a short corridor with two sets of lifts on the left and access to the main stairwell on the right. Beyond them it widened out into an open atrium four storeys high. This, I'd been told by Johnson, was the Cage where the mice could hang out, mingle and chill. You could hear the air quotes around 'chill' when he said it.

From the point of view of us Vogons it was also home to the storage lockers where everyone, including me, was supposed to stash any outside electronic devices while at work. The lockers were the standard metal cubes with electronic locks keyed to the RfiD in our ID cards. The doors were randomly painted as a single square of one of the colours of the rainbow, with a number stencilled on in white or black - whichever contrasted best. You were not supposed to have a personal locker, but instead pick the first one available. Because the lock was keyed to your ID card, the locker sprang open automatically when you left the building. Long-term storage was forbidden.

Now, personally, if I was managing a building full of poorly socialised technophiliacs I would have gone for personal lockers and mechanical locks. When I asked Johnson about this, he said he'd made that very same suggestion his second week on the job, but management said no.

Any employee could check out a flip phone for use within the building. These were simple digital mobile phones which were restricted to internal calls only. They were offcially called babelphones - all calls to and from the outside were routed through the company switch- board and logged. But the majority of the mice didn't bother, because they spent most of their working hours logged into the company intranet - where they were much easier to contact.

The rest of the Cage was painted in bright pastel blues, oranges and pinks and was arrayed with tables, blobby sofas, beanbags and a table-tennis table. Vending machines lined the walls and there was a genuine human-sized hamster wheel in one corner, with a bright blue cable leading to an enormous plasma screen TV. Apart from a couple of guys who'd obviously pulled an all-nighter and then crashed on the sofas, the mice ignored the delights of the Cage and headed for their work assignments with the same grim determination as commuters on Waterloo Bridge.

The Serious Cybernetics Corporation prided itself on its lack of conformity and so the mice dressed with deliberate variety, although there were definite tribes. Skinny black jeans and a death metal sweatshirt, with or without a denim waistcoat, was one. Cargo pants, high tops, braces and check shirts were another - often with a floppy emo hairstyle that I thought had gone out of fashion when I was six. Lots of leggings in bright colours with luridly striped jumpers were favoured, but not exclusively, by the women. From my initial survey it was two thirds male and 95 per cent white. I did catch sight of a couple of reassuringly dark faces amongst the crowd. One of them, a short skinny black guy with a retro-Afro and a Grateful Dead T-shirt caught my eye and gave me the nod - I nodded back.

It was a good thing I had a towel wrapped around my head or I would have really stood out.

The Serious Cybernetics Corporation actually occupied two separate buildings. The entrance, the Cage, and most of the administration were part of a speculative office development on the corner of Tabernacle Street and Epworth Street that had gone bust in 2009. When celebrity entrepreneur Terrence Skinner made his surprise migration from Silicon Valley to Silicon Roundabout he snapped it up cheap - well, by an oligarch's definition of cheap.

But that wasn't enough, so he also acquired the five-storey former brick warehouse further up Tabernacle Street, and built enclosed walkways on the first and fourth floors to link them.

I knew all this because I'd taken the time to acquire the original building plans. What can I say? I like to be prepared.

Because of this layout, most of the mice were funnelled up a wide steel staircase that led from the floor of the Cage to a first floor mezzanine and then on to their open-plan offices, cubicles and conference rooms.

The Cage had balconies on the third floor which gave a good overview of the mice in their million hordes as they went to do... I had no idea what they did. When I checked them out, I saw Tyrel Johnson leaning casually on the railing and looking down at us. He spotted me looking up and beckoned.

I took the lift.

When I joined him at the railing I pointed at the towel around my head and Johnson smiled.

'Everyone has to wear one on their first day,' he said, and introduced me to my fellow Vogon Leo Hoyt, a white guy with darkening blond hair and cornflower blue eyes. He was wearing a credible navy M&S suit that had almost, but not quite, been tailored to fit.

We shook hands; his grip was firm and smile sincerely welcoming. I was instantly suspicious.

'Are we going to have a briefing?' I asked, which made Leo laugh.

'This isn't the police,' he said. 'We don't get briefings here. We have information dispersal conclaves.'

'Really?'

'Oh yeah,' said Leo, and grinned.

'Do we get one of those then?' I asked. 'Somebody is up to no good,' said Johnson.

'How do you know?'

'There are unexplained gaps in the security logs,' said Johnson. 'Just a few seconds here and there. Leo found them.'

Leo looked suitably smug.

'A glitch?' I asked Leo, who shook his head.

'They looked like deliberate breaks,' he said, hesitated and then admitted, 'I can't find a pattern though.'

'I want you to work the employee side,' said Johnson.

'Interviews?' I asked.

'No,' said Johnson. 'For the first couple of days I want you to wander around and stick your nose where it doesn't belong. Get to know some mice and get a feel for the place. Let them get used to seeing you around, and after a week or so you'll be invisible.'

Especially when I could take the towel off.

Before I headed back to rejoin the mice I asked Johnson whether he'd worn a towel on his first day.

'What do you think?' he asked, and I decided to treat that as a rhetorical question.

I started with the emergency exits, memorising positions and routes so that in the event of an emergency I would know where to guide people out. It's one of those weird truths you learn early on as police that quite a high percentage of the public have all the survival instincts of a moth in a candle factory. They run the wrong way, they refuse to move, some will run towards the danger, and others will instantly whip out their phones and take footage.

While I was studying the exits I took a moment to check the alarm systems that guarded them and tried to see if they were vulnerable to tampering either from the inside or out.

One place I couldn't check were the offices on the top two floors of Betelgeuse, the northernmost building. As far as I could tell, there was only one point of access for these - an enclosed skyway on the fourth floor that bridged Platina Street. Two similar skyways on the first floor gave access to the offices on the lower floors, but this one was different.

For a start, it was painted a sinister clean room white, had tinted windows and terminated in a plain blue door with a security lock that not only required the correct ID card but also a passcode as well.

'It's a secret project,' said Victor when we had lunch together.

'No shit, Sherlock,' said Everest, talking around a mouthful of pizza.

I'd met Victor and Everest during my initial wanderings. Everest had marched up to me in one of the multifunction floating workspaces and demanded to know whether I'd got my job because I was black.

'Of course,' I said, just to see what the reaction would be. 'I didn't even have to interview.'

He was a stout white man, heavy around the hips, face adorned with the traditional round glasses and neck beard and topped with a mass of curly brown hobbit hair. He was dressed in a purple OCP T-shirt, baggy khaki shorts, black socks and sandals. His ID card was purple and yellow and gave his name as Harvey Window. 'Told you,' he said to his companion - a short, round white woman with small blue eyes and brown hair cut into a short back and sides. She ignored him and held out a hand.

'My name is Victor, pleased to meet you.' There was a stress on the name that said here is a clue, let's see if you get one. I shook his hand and said I was pleased to meet him too.

'This is Everest,' said Victor.

Everest held out a clammy hand for me to shake and then, after the merest clasp, snatched it back.

'Let me make things very clear,' he said. 'We are the company assets and you are here to keep us safe. Not for your benefit, but for our benefit.'

'I live but to serve,' I said, which he seemed to accept at face value.

'Good,' he said and, turning, walked away.

'Everest?' I asked. 'Not Gates or Bill or Money?' Victor shrugged.

'Someone called him Update once and we almost had to call the police,' said Victor and sniggered.

'Really?' I asked. 'The police?'

'Really,' said Victor. 'He tried to take a bite out of an Asset Co-ordinator and if Tyson hadn't grabbed him I think he would have drawn blood.'

'Tyson?'

'Your boss,' she said. 'Tyrel.'

'Victor!' Everest called from across the room. 'We have that thing - remember.'

'Don't worry,' said Victor as he turned to follow Everest. 'We're the freaky ones - everybody else is normal.'

Later I'd made a point of hanging out on one of the balconies overlooking the Cage until Victor and Everest turned up for lunch, although of course at the Serious Cybernetics Corporation, lunchtime was an illusion. Once I clocked where they were sitting I wandered down and bumped into them accidentally.

The Cage had a truly mad array of snack machines, all of them completely free - the better to encourage the mice not to wander beyond the confines of the office. They were wonderfully varied and some, like the doughnut machine with the art deco stylings, were either antiques or reproductions of antiques.

I'd been boringly conventional and had a tuna and sweetcorn baguette from a machine adorned with a reproduction of Delacroix's Liberty Being Too Busy Leading the People to Pull Her Dress Back Up across its front. Victor had a box of sushi from a genuine Japanese automated sushi dispenser and Everest had a pepperoni pizza from a machine that purported to make it from scratch.

He stared at me as I sat down and continued to stare at me as I said hello and for about a minute after I start- ed talking to Victor, and then went back to his pizza as if I didn't exist. Occasionally he would take a series of precise slurps from a can of Mountain Dew, and he said nothing until I asked Victor about the top floors of Betelgeuse.

'Those are the Bambleweeny floors,' he said. 'And off limits.'

'What do they do up there?' I asked.

'Why do you want to know?'

'It's easier to guard something when you know what it is,' I said.

Everest's brow wrinkled as he thought about my answer. 'If Tyson didn't brief you,' he said, 'then you don't need to know.' Which showed a charming faith in the wisdom of hierarchies.

Victor giggled and put his hand over his mouth.

I gave him a quizzical look and he returned a little shake of his head and rolled his eyes at Everest who was diligently finishing his pizza.

'It's a mystery,' said Victor.

One way in which us Vogons differed from run-of-the- mill mice was that we had a definite shift pattern, so come five Johnson insisted I clock out.

'Tired people don't do their jobs properly,' he said, demonstrating one of the reasons why he'd left the police.

I took my towel with me and showed it to Beverley when I got home.

'And you wore that all day?' she asked.

'To be honest, I forgot I was wearing it after a while,' I said.

Eventually it got incorporated into Beverley's improvised Bulge support system but only after it had been washed. I said this was great, because now I would always know where my towel was, but that got me yet another blank look.

The next day I turned up for work sans towel, but I kept the suit. I managed to ingratiate myself with a number of mice and Victor invited me to join one of the floating role-playing games that assembled in one of the satellite conference rooms accessible from the Cage. 'Metamorphosis Alpha,' said Victor, when I asked what we were playing. Which turned out to be an ancient game from the 1970s with a horrible resolution mechanic but I'm not a purist about these things. Be- sides being fun, it was a useful way to get to know my fellow mice - the better to guard them from harm, or

themselves.

Leo Hoyt spotted us playing in the corner of the Cage and came over to glower at me, and then walked away shaking his head.

'I bet he prefers World of Darkness,' said Victor. Everest made a rude noise.

There were rumours that Terrence Skinner some- times sat in on these pick-up RPG sessions, although Victor and Everest said he'd never sat down with them. A lot of the mice didn't so much admire Skinner as worship the ground he walked on. He was famous for being the dull tech billionaire, the one whose company InCon nobody could remember the name of, the one that had made his fortune behind the scenes and wasn't blowing it on Mars rockets, sewage systems and genetically modified rice.

I wasn't introduced to the Great Man immediately - that was not how things worked at the SCC. Instead Terrence Skinner practised what he called 'management by walking around' which involved him striding through the various cubicle farms, trailing personal as- sistants and nervous project facilitators in his wake.

He tried to drop in on me unexpectedly on my third day while I was hot-desking in the Haggunenons' room. You could hear him coming twenty metres away, but Johnson had briefed me so I looked suitably surprised when he materialised at my shoulder.

'What are you doing?' he asked.

'I'm checking yesterday's entry logs for anomalies,' I said.

Terrence Skinner was a tall, rangy man with widely spaced blue eyes, thinning blond hair and thin lips. He wore an expensive black linen blazer over a faded blue Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy T-shirt with a picture of a smiley face with lolling tongue and hands covering its eyes. The words Don't Panic were written in large friendly letters next to the face.

'What kind of anomalies?' He had a strong, almost comical, Australian accent. An affectation, I knew, because I'd seen a TED Talk from five years previously when his accent was much less pronounced and almost hidden beneath a layer of West Coast tech-speak.

I was actually looking to see if there were any breaks in the CCTV coverage that corresponded with any particular person entering the building, only I wasn't about to announce that to Skinner's entourage - just in case.

'Anything irregular, double entries, duplicate IDs - that sort of thing,' I said.

'Do you think somebody's sneaking in?'

'It's always possible, sir,' I said. 'No system is foolproof.'

'Not when there are so many inventive fools, eh?' said Skinner who, I noticed, didn't invite me to call him Terry or even Mr Skinner.

I gave a convincing little chuckle, because it never hurts to ingratiate yourself with the boss.

'Yes, sir,' I said.

'I'm pretty certain that we have algorithms looking for that sort thing.'

'You never know,' I said.

A tall, athletic white woman dressed in a lightweight suit, one of the team of bodyguards that guarded Skinner in shifts, gave me a curious look before returning to her scanning-the-cubicles-for-lethal-threats routine.

You want to start with the snack machines, lady, I thought. That's an early death from Type 2 diabetes right there.

Skinner turned to the woman.

'I feel safer already,' he said, gave me a friendly nod and off he swept.

I asked Johnson about the bodyguards when I handed in the results of my anomaly search.

'Somebody tried to kill him in California,' he said. 'So he hired some specialist security.'

'Who was it tried to kill him?'

'It was just a carjacking,' said Johnson. 'But he got paranoid and wanted the extra reassurance. It's the fashionable thing to do in California - or so I'm told.' He glanced down at the printout I'd done for him. 'Anything tasty?'

I said as far as I could tell nobody was sneaking in.

Johnson grunted.

'They're sure it was a carjacking?' I asked. Johnson gave me a look.

'Who?' he asked.

'The American police.'

'Why do you care?' he asked.

'What if it wasn't a carjacking?' I said. 'What if it was a proper assassination attempt?'

'You think Google's out to get him?'

'He thinks it's serious enough, doesn't he? Why else did he get the bodyguards?'

'He has a personal masseuse, you know,' said Johnson.

'It might be a security threat,' I said.

'You really are fresh out of the Job, aren't you?'

'It might be though, mightn't it?'

Johnson sighed.

'The personal security of Mr Skinner is not our concern,' said Johnson. 'We're here for the premises and the mice. And somebody is sneaking around behind our back - I can feel it.'

'Gut instinct?'

Johnson waved his hand at his office door.

'Go play with the mice, Peter,' he said. 'find me a rat.'

And just to prove that the private sector wasn't that different from the police, I found the rat the very next day - entirely by chance.

I'd taken to swinging past the fourth floor skyway at random intervals. If Johnson had asked, I would have told him that its forbidden nature would attract the most rats. I really hoped he didn't ask, because it was a terrible excuse and the truth was I was dying to know what the secret might be.

A series of team meetings and high-level conference calls were scheduled for that afternoon, to coincide with morning on the West Coast of America. With most of the management tied up, the rest of the mice took the opportunity to skive off. If I were a rat, I thought, now would be a good time to poke about where I didn't belong. So I headed up to the fourth floor skyway to see if anyone was poking about up there.

I didn't actually expect anyone to be trying to break into the security door in broad daylight, so I was a bit surprised to turn the corner and find someone doing just that.

He was a skinny white man in his twenties, with black hair, long legs in spray-on black jeans and pristine white high tops. White T-shirt tight across his back as he leaned against the blue door - his open palm pressed where I guessed the lock had to be.

I considered letting him break in, but he must have heard me or something because he snapped away from the door and turned to face me. Which is when I recognised him.

'Hello, Jacob,' I said. 'What are you up to this time?'

Copyright © 2020 by Ben Aaronovitch

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details