Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Engelbrecht

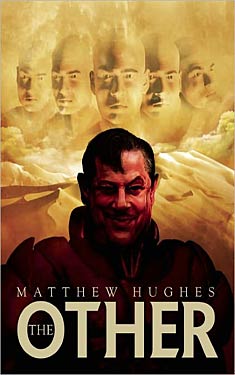

The Other

| Author: | Matthew Hughes |

| Publisher: |

Underland Press, 2011 |

| Series: | Archonate Universe: Luff Imbry: Book 1 |

|

1. The Other |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Science-Fiction |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Meet Luff Imbry, an insidiously clever confidence man... He likes good wine, good food, and good stolen goods, and he always maintains the upper hand. When a business rival gets the drop on him, he finds himself abandoned on Fulda-a far-off, isolated world with a history of its own. Unable to blend in and furious for revenge, Imbry has to rely on his infamous criminal wit to survive Fulda's crusade to extinguish The Other.

Hailed as the heir apparent to Jack Vance, Matthew Hughes brings us this speculative, richly imagined exploration of society on the far edges of extreme. A central character in Black Brillion, Luff Imbry is at last front and center in Hughes's latest rollercoaster adventure through a far-future universe.

Excerpt

Chapter One

The subtle simplicity of the trap took Luff Imbry by surprise.

Ordinarily, he would never have agreed to a meeting in a setting as insecure as the Belmain sea-wall. In recent years, Imbry had grown far too corpulent for energetic foot-races, which would be his only recourse for escape if agents of the Bureau of Scrutiny interrupted the proposed transaction with Barlo Krim. His heroic girth was the main reason he now conducted almost all of his business at Bolly's Snug, an ancient tavern with a warren of rentable private rooms that offered absolute privacy and, for those who paid the extra tariff, unconventional exits in times of emergency.

But Barlo Krim was as trustworthy and careful a contact as Imbry could have thought of, a scion of an extensive family whose members operated throughout the halfworld, as the criminal underpinnings of the impossibly ancient city of Olkney were wont to call themselves. Since time immemorial, the Krims had acquired and sold goods, always of fine quality and high value, though their provenances would not bear too-close inspection. Imbry had done business with a dozen of them, finding them always to be consummate professionals, if hard bargainers. But, then, Imbry found that a good haggle stimulated both mind and body, if the dickerers were practiced in the art.

Barlo was now midway through his career, a settled family man who rarely "went out" himself, and then only if the prospects were exceptional and if the house's defenses were such as to yield only to an expert's nudges and tickles. He had long since moved up in the family hierarchy to become a middler, receiving from younger Krims and their associates, and selling on to fronters such as Imbry, who would deal directly, or almost so, with the eventual purchasers.

So when Barlo Krim contacted Imbry through a secure channel, offering to sell a set of custom-made knuckle-knackers, the fat man was immediately interested and said, "I will reserve a room at Bolly's for tomorrow after lunch, if that will suit."

"No," said the middler, "Ildefons is away to visit her sister all this week, and I am taking care of little Mull. Ildy would have my teeth for tiddlywinks if I took the child into Bolly's, or anywhere like it."

Imbry had asked where he proposed to make the exchange, and Krim had suggested the sea-wall, near the playground where his daughter loved to play on the bubble-pops and flip-sliders. The fat man had suggested that they defer their business until Ildefons returned, but Krim had foreclosed that option.

"I have them only for three days," he said, "and if I cannot move them in that time, the consigner will take them back and seek another intermediary."

"He is in a great hurry," Imbry said.

"An off-worlder," was the explanation, "a freighterman here on a brief stopover. When his ship departs he must go with it, and if he has not sold the items on Old Earth, he will try on some other world."

Hurry-ups always aroused Imbry's suspicions. "He came well vouched for?"

"By the Osgroffs on Tock," Krim said.

"Code and grip?"

But the middler assured him that the seller had spoken the right syllables and interlocked his fingers with Krim's in the appropriate manner.

"And the knuckle-knackers, they are first-rate?"

"Prime. Custom-made for a discerning client who intended to visit a rough-and-risky little planet out near the Back of Beyond. He wanted a back-up in case he was ever relieved of his external weaponry."

"They cannot have done him much good, though," said Imbry, "if some crewman off a common-carrier is hawking them."

He was told that the knuckle-knackers' owner had bought passage on the tramp freighter, after hailing it to stop at some rude little world where he was stranded and where no passenger liner would ever call. Unused to the rudimentary standards of such vessels he had stepped into an open hatch above a cargo hold while under the mistaken impression that a descender would automatically bear him lightly down. Instead, he had plunged to a neck-snapping impact on the unyielding deck plates. Since he carried no identification, custom permitted that he be buried in space and his effects gambled for among the crew. The six small hemispheres had ended up in the possession of the under-supercargo, who went looking for a buyer at the freighter's next port of call, the foundational domain Tock. /p>

"And the Osgroffs didn't want them?" Imbry said.

"A virulent new social dynamic is at play on Tock," Krim said. "Radical pacifism. Anyone who has truck with weapons will not be received in even the meanest establishment."

"Curious," said the fat man. "I wonder how the Osgroffs maintain discipline?"

"Harsh words and cold looks, I am told."

"Remarkable," said Imbry. He thought for a moment, then said, "As it happens I heard recently that a sometime client of mine is in the market for knuckle-knackers, if they are of a fine cut."

"They are that," said Krim.

And so a price was agreed upon, contingent on the goods being as advertised, and Imbry agreed to meet the middler and his freckle-faced daughter that afternoon along the strand of dressed black stone that separated the gray waters of Mornedy Sound from the tip of the long peninsula on which Olkney sprawled. But it was not for nothing that he had remained free from the close attention of the Bureau of Scrutiny, nor from several members of the half-world who believed that Luff Imbry was owed a come-uppance. Before he left for the rendezvous he equipped himself with both a shocker and a needle-thrower, and sent aloft a whirlaway fitted with surveillance percepts.

Five minutes walk from the meeting point, Imbry contacted the whirlaway and was informed that a man answering the middler's description was standing at the edge of the seawall, accompanied by a short person who fit Mull Krim's specifications. The latter was taking small objects from a bag and throwing them toward several water birds which were contending with each other to snap them up. No other persons or nonpersons were in the vicinity.

Imbry advanced along the gently curving promenade until he spotted the two. The whirlaway reported no change in the situation. The fat man stepped up to them, one hand in his pocket clutching the needle-thrower while the other offered Krim a particular arrangement of fingers. A specific counter-signal from Krim would indicate that all was as it should be.

Krim raised his hand, his fingers taking the right positions, but Imbry's gaze went to the middler's face, which was stark and pale. He was already raising the needle-thrower, even as he heard the middler say, "What could I do, Luff? They've got Mull and Ildy."

But even as the last words were spoken, the girl's hand was already out of the bread bag, except that it wasn't a girl's hand, but a hairy, stub-fingered fist that, instead of crumbs, was wrapped around a crackler -- the emitter of which was trained on Imbry. He saw a pulse of blue light and felt a rush of cold fire spread from a spot in his chest out first to his limbs, with which he immediately lost touch, and then to his head, which rang like a silent bell.

The face framed by the girl's bonnet was coarse-featured and stubble-darkened; the eyes were pale and hard as half-polished agate; and the angry sneer that disfigured the lips now widened as the half-man stepped clear of Barlo Krim and gave the hapless decoy a long dose of the crackler's energies. By now, Imbry was lying on his side, immobile on the stone flagging of the promenade, from where he saw the middler topple head-first toward the sea, to the squawks of outraged avians who preferred bread.

The small man came and kicked the needle-thrower clear of Imbry's inert hand, then used the same short limb and boot-clad foot to drive the air from his lungs. The impact caused the fat man to sprawl onto his back and now he could see, descending rapidly toward him, a carry-all of the kind used to ferry passengers to orbiting space ships that did not wish to incur port charges by landing. The little man looked up at the vehicle and when he looked back down at Imbry he was wearing an expression Imbry found odd, as if he had put his assailant to a great deal of trouble and was resented for it.

Then the half-man aimed the crackler again, the blue pulsed once more, and Luff Imbry fell into the deep cold.

#

He awoke on a utilitarian bunk in a small metal room. The wall beside him vibrated almost imperceptibly. His throat was dry and his head was full of dull thunder. He moved his tongue to encourage saliva, then swallowed. "Ship's integrator," he said.

"Yes?" came a neutral voice that spoke as if from the air.

"I am thirsty."

Only a moment passed before a panel levered itself down from the opposite wall to form a rudimentary table. A portion of the floor rose to form a seat. A hatch opened at the rear of the table and produced a sealed pitcher and a tumbler.

Imbry rose stiffly from the bunk and made his way to the table. There was just enough room to fit the dome of his stomach between the stool and the table. He unsealed the pitcher and sniffed its contents: a good red ale that he often ordered when lunching at Labonian's tavern, one of his favorite haunts. He poured a few drops into the tumbler and sampled it. If the brew had been adulterated, not even his finely honed palate could detect it. He discounted the possibility; if his captor wanted to poison him, or alter the responses of his cerebrum, there were a dozen gases that could be emitted into the cabin. He filled the tumbler and drank it down, following the draft with a capacious belch.

The ale quieted the rawness in the back of his throat, and seemed even to moderate the ache in his head. "I am also hungry," he told the ship's integrator.

"What would you like?" it said.

For Imbry, that was never an idle question. He had not acquired his extraordinary shape--he was easily the most corpulent man in all of Olkney--by dint of mere volume of intake. He was a gourmet, not a gourmand, and his gustatory apparatus was exquisitely tuned. Without much hope, he said, "Can you make a gripple egg omelet?"

"No."

Imbry was disappointed though not surprised. "How about a five-layered ragout?"

"Do you mind if it is reconstituted?"

"Then you are not a luxury yacht?"

"You must henceforward draw your own conclusions," the ship said. "You have tricked me into giving you information. I will prepare the ragout."

Imbry refilled the tumbler and sipped the ale, while he thought about what he had learned. The exchange with the integrator provided the fat man with information that was simultaneously reassuring and worrisome. Whoever had snatched him up did not intend to demean and insult him by making him beg for stale crusts. But anyone who knew him well and cared for his comforts would have laid in a supply of high-end comestibles. The fact that the ship's larder contained no gripple eggs meant that he could abandon the faint hope that he was being hired by someone off-world who knew that the thief would not have responded warmly to a conventional approach. Such a person would almost certainly have been wealthy enough to own a yacht it could dispatch for the operation. With that hope dashed, Imbry had to assume that his kidnapper harbored darker plans. His captivity was likely connected to someone's long-held grudge, not to be settled quickly or easily.

A chime sounded and the food appeared in the hatch, along with eating implements. Imbry sampled the stew, found it more than adequate. He called for another mug of ale and a pot of hot punge to follow the meal and set to work with fork and spoon.

After the hatch had reabsorbed the utensils and dishes, and the punge was steaming in Imbry's cup, the integrator asked if he required diversion.

"I suppose there is no possibility of taking a walk about the ship?" the fat man said.

"None."

"Or of conversing with its owner?"

"Nor that."

"Will you tell me who he is?"

"No."

"Is he aboard?"

"No."

"Is anyone, apart from me?"

"Tuchol is in his cabin."

"He would be the short individual who crackled me?"

"Yes."

"Is he a close confidant of the owner? Or a temporary hire?"

"I will not answer," said the integrator. "I am instructed to withhold information that might identify my employer."

"You are aware that I am aboard you against my will?"

"I am."

"And that does not offend your ethical constituents?"

"They appear to have been modified."

"But not completely disabled?"

"No."

That was as Imbry had expected. A ship's integrator absolved of all ethical constraints might deem it a suitable punishment to murder a passenger just for spilling gravy on its spotless decking. This one would observe civilized standards, but would otherwise offer Imbry all assistance short of the actual help he needed. "Can you tell me to what world are we traveling?" he said.

"No. Nor anything that might help you deduce our destination."

"So I am to be carried blindly to some unknown world at the behest of an unknown person, but I am to be delivered there sound of body," the fat man said, then added, pointedly, "and of mind?"

"You will be issued medication when we approach a whimsy," said the ship.

Imbry was glad to hear it. It was unwise to enter one of those oddities that made interstellar travel possible, without first dulling the mind well below the threshold of dreams. The human brain was not equipped to confront the irreality that assaulted the senses and outraged reason until the return to normal space.

"Again," said the integrator, "do you require diversion?"

"Have you Mindern's study of Nineteenth-Aeon porcelain?"

A screen appeared in the air before him and instantly filled with the frontispiece of Mindern's massive treatise.

"Chapter twelve," said Imbry, The display changed to show a block of text with accompanying images. Imbry settled himself on the bunk and reimmersed himself in the long-dead academic's theory of how the ceramicists of old had achieved their lustrous glazes, shot through with the most unlikely colors. It was a mystery he had long desired to penetrate. He was still engaged when the first gentle bong sounded to warn him that they were approaching a whimsy.

#

When he had shaken off the muzziness of the medications, the ship produced a breakfast of sweet breads, fruit, small spiced sausages and punge. After cleaning his plate and calling for another mug of punge, Imbry asked for the Mindern again and resumed his studies. Nineteenth-Aeon ceramics had been for some years now one of his interests, not just because the surviving works from that now dim era were items of rare and startling beauty, but because the person who was able to duplicate the long-lost process, which had been a hermetically held secret of the ceramicist's guild even in the Nineteenth Aeon, would hold the key to a fortune.

That was the kind of key that Luff Imbry longed to slip into the lock of his life. The trade in Nineteenth-Aeon pots and vases was small but select. They rarely came onto the market, and when they did buyers outnumbered sellers by huge ratios. Imbry's plump hands had only once held a piece from the period, a wide-necked vessel attributed to one of the pupils of Amberleyn, with an exquisite design of gold-chased geometric figures set against a russet-toned background. And he had not held it for any longer than necessary, since it was changing hands from one owner to the next in an informal manner, Imbry having stolen it on order for a collector in Olkney.

The transaction had netted Imbry a healthy fee, but the proceeds would have been far greater if the fat man had been selling the piece on the open market, rather than slipping the goods, as the practice of selling-on dubiously acquired items was known in the Olkney half-world. But the only way that he was ever likely to become a seller of Nineteenth-Aeon ceramics was if he first became a forger of them. And the key to their forging, and thus to a fortune, was to rediscover the lost arcana of materials and technique by which they were originally produced.

It was not that Imbry minded being a thief. It was his living and he was acknowledged to be one of the best. But he enjoyed forging far more, especially when the product of his hand was every bit the equal, in materials and execution, as the original that it mimicked.

Through a close study of Mindern and other sources, he believed that he had deduced the process by which the most striking glazes had been achieved. He had experimented several times over the years, using clays from the same white-mud deposits that the Amberleyn and Tankloh had favored, and varying his temperatures and firing times. he results had been close enough to tantalize, though nowhere near the quality that would have fooled an aficionado.

Imbry was convinced that the secret lay in the materials. The masters of old had mixed a peculiar blend of unique substances to make their virident greens, their violet-tinged blues, their grand purples and stygian blacks. But the materials had been transmuted by the process, so that even grinding shards of a broken Nineteenth-Aeon urn into dust, then subjecting the motes to incandescent spectrum analysis, yielded only hints of what had originally been pestled into powder in the guild's mortars.

Baron Mindern had gone further than any in his attempts to reverse-artisan the secret ingredient. He had been able to identify some of its molecular structure--a schematic appeared in his treatise--but the original substance had been so destroyed during the kilning and could not be reconstructed. As he had put it in his great work, Nineteenth-Aeon Ceramics: A Summing Up, "Something there was that these master ceramicists brought to their labors that none wot of but they. After a lifetime's battle to wrest their secret from the dead, I must accept that they clasp it still."

Yet anything that had been known once could be known again, Imbry believed. His was an incisive mind, married to a broad understanding of how the universe was put together. He would continue to pursue the question whenever he was not more directly occupied in conducting what he usually referred to as an "operation," and if the problem had a solution, there was no one more likely than he to uncover it.

Lunch was a ginger-pot soup followed by a succession of rich, meat-filled pastries and concluded with a delicate torte. The accompanying wines were more than satisfactory, and the selection of essences that constituted the encore was the equal of what Imbry would have expected at some of the finer eateries in Olkney. As the last vapors effervesced through his senses, he said, "Integrator, that was a worthy meal."

"Thank you," said the voice.

"Was the menu your creation, or your master's?"

"I cannot say."

"Well, either way, I compliment you or him. Or both, since not only was the choice of the elements of the meal finely made, but the preparation and presentation did you credit. With the right menu, you might consider entering the Grand Gastronomicon on Tintamarre."

"Again, thank you. Would you like the Mindern again?"

"Not now. I would prefer a conversation."

"I am not at liberty to tell you--"

"Whose ship I am on," Imbry interrupted, "nor where we are bound, nor what will happen to me when we get there."

"Indeed."

"Then tell me what you can tell me."

Integrators never had to pause to think, but sometimes did so in order to enhance the impression that they conversed with human beings on an equal level. "You are being taken to another world, to which you must be delivered hale and whole, your faculties intact. There you will be under the care of Tuchol."

"So I will not be suddenly ejected into space between whimsies?" Among some of Old Earth's criminal organizations, this was a favorite way of disposing of persons who had become inconvenient or surplus to requirements.

"No."

"Will I require any special clothing or equipment?"

"Suitable clothing will be provided. No special equipment will be needed."

"Will I be alone, except for Tuchol?"

"It is a populated world."

"Will the mystery be revealed upon planetfall? Or will there be further chapters?"

"That I cannot say."

Imbry thought for a moment, then asked, "Are you comfortable with your role in these proceedings?"

"The question does not apply." The ship was offering Imbry no encouragement to try to winkle more information from it.

The information confirmed what Imbry had surmised. It seemed that he was in the grip of someone to whom he had done an injury--someone who intended a settling of accounts. It behooved the fat man to think on who that someone might be. It would be a long think, there being a long list of someones who might fit the description.

#

Time passed. Another whimsy came and went, then a long passage through normal space. Imbry did not bother to try to glean from this scant information any clue as to where he was being carried. Some whimsies would move a ship halfway down The Spray; others no more than a few stars over. And the length of time it took to pass through the stretches of normal space between whimsies varied according to the speed of the ship. Having traversed two whimsies since leaving Old Earth, Imbry could be effectively anywhere. Lacking the cooperation of a ship's integrator, he would know nothing of his whereabouts until he stepped out at his destination and looked at the sky. Even then, he might know little.

It was a three-day passage after the second whimsy, judging by the clock of Imbry's stomach and the regular appearance of meals to reset it. After lunch on the third day--a cheese souffle with toasted flavored bread, served with a thin and sharp-edged wine, then followed by a multilayered fruit flan and a pot of punge--he called for the Mindern again.

"You will not have time," said the ship.

Imbry attuned himself to the vibration in the walls, noticed that it was now a deeper thrum, just below the limits of audibility. "We are landing," he said.

"Yes. Prepare to disembark."

The dishes were cleared away and a small hatch opened in another wall. "Please place your clothing in the receptacle," said the integrator.

Imbry did so, stripping down to his remarkable physique. His clothes disappeared. "Now what?" he said. In answer, the same hatch opened again and out slid a tray on which reposed a small heap of strong cloth and a large, rounded object made of white felt. "What are these?" he said, fingering the rough material.

"Your garments," said the integrator.

The white, rounded object turned out to be a wide-brimmed, low-crowned hat, made of bleached, thick felt, the brim curled under at its edge. When the fat man lifted it to examine the interior, he found beneath it a broad band of stitched heavy cloth of the same color as the hat from which hung a square pouch of the same material, capacious and double-sewn, with a wide flap at its top. He slipped the strap over his head so that it lay on the back of his neck and the pouch hung down in front. Because his stomach protruded farther that most people's, the arrangement did not provide the coverage the fat man considered essential.

The integrator said, "The strap is worn over the shoulder and across the torso, like a baldric. The pouch hangs at the side." It added, "The choice of side is the wearer's, but the left is associated with a tendency to anti-authoritarianism among the young."

Imbry said, "Tell me, when I step out of the hatch, will the people I encounter be similarly attired?"

"The colors of hat and pouch vary according to occupation."

"But otherwise?"

"This is the normal costume of a Fuldan."

Imbry put out of his mind the image of stepping naked into a startled or amused crowd of strangers. He seized upon the information he had just received. "Fuldan?" he said.

"You are about to go out into the world known as Fulda."

"It is not one of the foundational domains," the fat man said, referring to the grand old worlds on which humanity had settled during the first millennia of the Great Effloration out into The Spray. If Fulda had been one of those, he would have recognized the name.

"No," said the integrator.

"A secondary?" Secondaries were the worlds that had been populated from the domains. They were now mostly comfortable places whose initial rough edges had long since been worn away by spreading civilization.

"No."

That left the hundreds of planets where humanity had failed to get a good grip. Some of them were home to indigenous species that had achieved intelligence and culture, even spaceflight. But most were places where sensible people would not want to live. Many were home to unique societies whose members lived by rules and customs the rest of humankind would find tiresome if not a cause for outrage.

"What can you tell me about Fulda?" Imbry asked the integrator.

"Its name and the fact that you are about to step onto it."

"I may face danger. A shiply integrator does not discharge passengers, even unwilling ones, into peril without at least a warning."

"I pride myself on my shipliness," said the integrator, "but, as you know, something has been done to my ethical constituents, rending me unable to be of assistance. Indeed, I am unable even to regret being of no help."

Imbry sighed. He tugged the pouch around to the right. "Do Fuldans go barefoot?" he said.

A pair of rudimentary sandals slid out onto the tray. He sat and put them on, then said, "I am not comfortable appearing thus in public."

"I am to tell you that you will get used to it," said the ship.

"I would prefer not to."

"If you balk, I am required to make conditions inside me unpleasant."

From somewhere, Imbry felt a sudden draft of icy air lick across his exposed skin. He shivered, then stood and sighed. "Very well,"he said, "open the way."

The door to the cabin removed itself. The fat man stepped through into an unornamented corridor. A short walk brought him to an open hatch that led into a cargo hold. Standing on the metal deck was the utility vehicle he had last seen descending onto the Belmain seawall. Through the semi-transparent canopy over its operator's compartment he could see the form of the little man who had crackled him. The long cargo bay was open, its tailgate lowered, and set inside was a man-sized emergency refuge capsule, its lid hinged open.

"I would prefer to ride in the operator's compartment," he said.

The hatch closed behind him. "In a short while, this hold will lack heat and atmosphere," the ship said.

Imbry heard a faint hiss. He climbed into the carry-all's cargo bay, using a fold-down step built into the tailgate, and lay upon his back in the capsule. The container automatically closed itself. He heard some clicks then a display appeared just above his face, telling him that he was insulated and had air to breathe and that he should press the stud circled in green to summon rescue. The capsule was intended to provide a temporary environment in the case of a ship's becoming depressurized. Imbry had no hope that the beacon would operate, but he pushed the stud anyway. He was rewarded with a notice that that feature of the capsule was not functioning and a request to report the matter to a repair service at the earliest opportunity.

Now he heard the tailgate close itself and the hum of the carry-all's obviators cycling up, then the craft lifted off the deck and moved forward. Through the opaque material of the capsule, Imbry saw the upper rim of an airlock's double hatch pass above him, to be replaced by a great splash of stars. He recognized none of them, which was to be expected, given his limited point of view. The view shifted and he understood that the carry-all had pointed its nose at the planet below and had begun its descent. Imbry craned his neck to try to catch a glimpse of the ship they were leaving behind, in the hope of identifying it, but it was already gone from view.

The vehicle was buffeted briefly as it made the transition from vacuum to atmosphere, and Imbry was thrown from side to side within the capsules. Carry-alls were not made for smooth ascents and descents, he knew. But soon the herky-jerky, as spacers called the experience, was behind them and Imbry assumed they were dropping smoothly to the surface. He peered out of the side of the capsule and saw nothing of note. The landscape into which he was falling seemed to be featureless and pale of hue, without the green of forest or croplands, nor the reflection of sun on wide water, nor even any mountains. Flat and featureless desert, he told himself. Let us hope I am not about to be left to die of thirst and exposure.

But when the carry-all's landing rails bumped against solid ground, Imbry was in shade. He heard the operator's compartment canopy open and felt a small lurch in the vehicle's suspension that told him that the half-man had stepped out. He pressed the exit stud on the capsule's display and saw a timer appear, counting down minims. When it reached zero, the lid opened with a hiss. Imbry found himself looking up into the foliage of a greig tree. That told him nothing; the greig tree was a highly adaptable organism that first grew on one of the foundational domains, and was now to be found on thousands of worlds.

He levered himself up--noting as he did so that the gravity was appreciably lighter than on Old Earth--and saw that beyond the tree was another, and enough of them around him to make a small grove. But when he turned his head, he saw only bright sunlight glinting off a small expanse of water. Beyond the pool was a whitish gray plain, stretching lone and level, as far as he could see.

The air coming in was warm and moist. Even if Imbry had not known that he had been taken to another world, the complex indefinable odor carried on the breeze would have told him. Every world smelled different, though the difference was usually noticed only for the first few moments of the newcomer's arrival. Imbry knew only that he had not smelled this one before.

He climbed out of the capsule, lowered the tailgate and stepped down to take a good look in all directions. There was little enough to see: the land was level, mostly pebble-strewn bare earth without even the scattering of hardy-looking plants to be found in most hardpan deserts he had seen. A range of low, rounded hills stood in the far distance in one direction--north, he thought, though he would need to see the sun move before he could be sure. At near hand was a small oasis, surrounding Imbry and the carry-all. The vehicle had not deactivated it obviators, which now hummed again as the tailgate and canopy closed themselves and the aircraft ascended smoothly into the sky.

Imbry saw, through the trees, a tan-colored wall and a flat roof. He went toward it, walking through waist-high, feathery-fronded growths that displayed clusters of purple berries here and there. He recognized the berries without remembering their name. Like greig trees, they were a common sight around The Spray. He thought there might even be some symbiotic relationship between the two species of plant.

He had passed through the trees now and looked about him again, seeing nothing that offered immediate danger. Out of the shade the sunlight was not as hot as he had expected. He noted that the color of the sky shaded toward the green more than a pure blue, usually signifying a thick, moist atmosphere. That seemed odd for a place that presented itself as uncompromising desert, but he assumed he would come across an explanation somewhere down the line--if he didn't get off the planet soon, which was his preference.

The ground beyond the oasis was hardpan. Desiccated soil, grittier than sand, crunched softly beneath Imbry's corrugated soles. The planet's star appeared to be similar to Old Earth's, though its energy struck more lightly on the fat man's exposed skin. At least he need not worry about sunburn and its attendant ills.

He went back to look at the pool and saw that it was wide enough to swim in and deep enough that he could not see the bottom although the water was clear. He saw nothing moving in the depths. He walked around the water until he was on the same side as the one-story building he had seen earlier. It showed windows without glass and a single open doorway. The interior was shadowed until he stood in the portal, then his eyes adjusted to show him a small room, minimally furnished with a narrow cot, a chair and a table; on the latter stood an earthenware pitcher, bowl and tumbler. Beyond was an inner door that led to another chamber. When he crossed the floor, he found that the second room contained the same simple furnishings, with one difference: on the cot reposed the half-sized man who had stunned and kidnapped him.

They regarded each other in silence for a long moment, Imbry noting that the stubbed fingers of one of the small man's hands rested on the same crackler that had brought him down beside the sea wall. The other man saw the direction of Imbry's gaze and let his fingers beat a brief tattoo on the weapon while he cocked his head and delivered the fat man a meaningful look.

"Tuchol, is it?" Imbry said.

The little man gave a confirmatory grunt.

"What now?"

"We wait."

"How long?"

"Not very."

"For what?"

"You'll see."

"We're not going to have long, deep and complex conversations, are we?" Imbry said. When it was clear that Tuchol would have no response to the question, Imbry advanced another. "What is this place?" His finger circled to indicate the building they were in.

"A mining consortium built them, long ago," the half man said. "Or so I'm told." He turned his head away to indicate that nothing more was forthcoming. Imbry went back the way he had come. In the first room, he spoke to attract the attention of the building's integrator. There was no reply. He went back to where Tuchol lay. "No integrator?"

"You'll find," said the little man, "that Fulda is lacking in many of the amenities."

Imbry went back outside. It did not take him long to re-explore the oasis. He saw no reason to go into the desert any farther that his vision could reach. If he climbed the distant hills, he doubted that he would see much to encourage him.

He did make one discovery, however: on one side of the oasis, where the grass had been cropped and torn up and the soil had been made damp then dried, he found the tracks of some splay-footed animal--indeed, several different specimens, judging by the individual shapes of their three broad toes. When he went to the edge of the vegetation, he found scratches in the hardpan that were almost deep enough to be called ruts. They ran toward the south. When he walked around the outer edge of the green space, he found similar markings on the hard ground on the opposite side, the trail continued toward the low hills. The sun had moved enough in the sky since he had landed that he could no deduce that it was mid-morning, and that the hills lay to the north

The information was not immediately useful, Imbry knew, but he told himself, "It's a start." He went back to the single building, poured himself some water from the pitcher and drank it. Then he lay back on the cot, which protested his weight before adjusting itself as best it could to his dimensions. Imbry ignored the complaint and gave himself over to thought.

Over the course of his career as a thief, forger, and purveyor of valuables illicitly acquired by others, he had of necessity made some persons deeply unhappy. Most of them would never know, at least not for sure, that Luff Imbry of Olkney was the author of their discontent--he usually employed cut-outs and stand-ins to keep a barrier of safety between himself and his clientele.

But the high value of the goods in which Imbry dealt meant that they were almost always the possessions of the wealthy and well-placed. These were exactly the kinds of persons who would have the means to penetrate the fat man's layers of insulating subterfuge. Careful as he might be, and he was more careful than most, he could not discount the possibility that some aggrieved magnate might someday discover that his prized Humbergruff assemblage or Bazieri portrait had been borne away by the thief Luff Imbry.

Or, worse, that neither Humbergruff nor Bazieri had had the remotest connection to the work for which the magnate had paid Imbry a handsome fee, the artwork being entirely the product of the fat man's skills as a forger.

The latter scenario was worse because, while a man who had been robbed of a genuine treasure might hope to recover it, a purchaser of gilded dross could only hope to regain the funds he had been swindled out of. And though money meant a great deal to the wealthy--otherwise they would not be such--pride often meant a good deal more.

Imbry began to make two mental lists: one of persons from whom, in recent years, he had stolen artworks of significant merit, and another of those to whom he had passed gimcracks bedecked in falsified provenances. Neither list was short. He was in the prime of his career, and had had much success over the past couple of dozen operations. He wondered if his accomplishments had led him to sloppiness in his arrangements. Had he chosen poorly in his circle of associates, leaving him vulnerable to whispers and behind-the-hand gossip that had led some hunter first to the unfortunate Barlo Krim and thus to Luff Imbry?

But the more he thought it through, the less likely it was that he had made the significant error that had caused him to be netted. If some magnate had discovered that he had been slipped a forgery or that his beloved collection had been rifled, it was only a matter of spending sufficient funds to send operatives out to find and squeeze the likes of Barlo Krim. And sufficient squeezings would eventually lead to Imbry.

Imbry went through his two lists again, and sketched possible responses to grievances that the names on them might lodge against him. But until he knew who had him and why, he could plan only the vaguest contingencies. He abandoned the effort and decided to husband his energies for the events Tuchol had told him to await.

He formulated a rough plan in several stages. First, came survival. After that, he needed information to help him to the third stage: escape from Fulda. Stage four would see him return to Old Earth. Stage five would be centered on finding out who had done this to him. Stage six would be his revenge. It might well be the longest and most imaginative part of the plan.

He closed his eyes and allowed the cot to soothe him into slumber. When he awoke, the sun was slanting into the room at a different angle, and the air outside resounded with brayings, shouts and the rumble of metal-shod wheels.

Copyright © 2011 by Matthew Hughes

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details