Added By: valashain

Last Updated: Engelbrecht

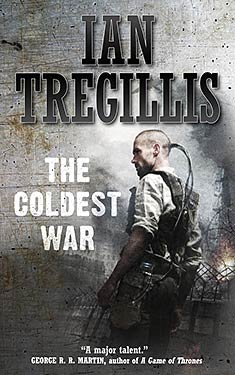

The Coldest War

| Author: | Ian Tregillis |

| Publisher: |

Orbit, 2013 Tor, 2012 |

| Series: | The Milkweed Triptych: Book 2 |

|

0. What Doctor Gottlieb Saw |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Alternate History (Fantasy) |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

For decades, Britain's warlocks have been all that stands between the British Empire and the Soviet Union - a vast domain stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the shores of the English Channel. Now each wizard's death is another blow to Britain's national security.

Meanwhile, a brother and sister - the subjects of a twisted Nazi experiment to imbue ordinary people with superhuman abilities - escape from a top-secret facility deep behind the Iron Curtain. They head for England, because that's where former spy Raybould Marsh lives. And Gretel, the mad seer, has plans for him.

As Marsh is once again drawn into the world of Milkweed, he discovers that Britain's darkest acts didn't end with the war. And while he strives to protect queen and country, he is forced to confront his own willingness to accept victory at any cost.

Excerpt

one

1 May 1963

Arzamas-16, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, USSR

Gretel laid a fingertip on Klaus's arm.

"Wait," she whispered.

Several seconds passed while she consulted some private time line that existed only in her head. He recognized the look on her face: she was remembering the future, peering a few seconds ahead.

Then she said, "Now, brother."

Klaus pulled the merest trickle of current from his stolen battery, just enough of the Götterelektron to dematerialize his hand. It was a gamble, one Gretel had assured him would work. But he'd practiced for weeks.

His hand ghosted through ferro-concrete. He wrapped his fingers around one of the bolts that sealed the vault. Klaus concentrated, focusing his Willenskräfte like a scalpel, and pulled a finger's width of steel through the wall. Gretel caught the slug before it clattered to the floor and gave them away.

They repeated the process twice. Klaus severed all three bolts, and the alarm circuit, in fifteen seconds. But the damage to the door was strictly internal; a passing guard would see nothing but pristine, unblemished steel.

It would have been easier for Klaus to walk straight through the wall with his sister in tow. But that would have tripped sensors and triggered their captors' fail-safes before he was halfway through. The entire facility, this secret city the locals called Sarov, bristled with antennae and circuitry attuned to the telltale whisper of the Götterelektron. Unauthorized expression of the Willenskräfte instantly triggered the electromagnetic equivalent of a shaped charge. The British had developed a crude precursor to this technology back during the war; they'd called their devices "pixies," and they had a range of a few hundred meters. The Soviet fail-safes could knock out a battery at six kilometers. Klaus knew the specs because he'd helped them test the system. He'd had no choice.

Gretel never worried about the fail-safes. Klaus stood on the cusp of fifty (according to his best estimate; he and his sister had been war orphans) and yet he still didn't know how or when Gretel called upon the Götterelektron to see the future. He suspected she relied upon batteries far less than she let their captors believe, and not when they thought she was using them. It had been that way back home in Germany, too.

They eased the vault door closed after slipping inside. Klaus groped for the light switch. Sickly yellow light cascaded from the naked bulb overhead, chasing shadows past rows of cabinets and shelves. A musty smell permeated the vault; their footsteps kicked up swirls of dust. The Soviets still referred to this place, almost reverently, as ALPHA. But they came here rarely these days.

The cabinets contained papers the Soviets had obtained during their lightning-fast occupation of the old REGP, the Reichsbehörde für die Erweiterung Germanischen Potenzials; the shelves held physical artifacts from Doctor von Westarp's farm, where the Reichsbehörde had lived and died.

Gretel and Klaus sought the batteries their captors had confiscated at the end of the war. He had managed, after months of preparation, to sneak a single battery past the Soviets' stringent inventory controls. But if his sister had foreseen things correctly (of which, of course, he had no doubt), they would need every millivolt they could muster on their long trek to the Paris Wall.

The rechargeable lithium-ion packs had been cutting-edge technology, decades ahead of their time in 1939. But they were blocky, bulky things, and hopelessly outdated compared to the sleek modules the Soviets had developed. Gretel's prescience aside, it was difficult to believe the Reichsbehörde batteries had retained any charge after twenty-two years. Klaus wiped away the layer of dust and grime coating the gauges. The batteries were degraded but still serviceable. If the gauges could be trusted.

Although Klaus had suffered tremendous misgivings about Doctor von Westarp's research, and had lost his unswerving faith in the Götterelektrongruppe long before the Communists' master stroke, he now felt a frisson of relief and pride. German engineering. A reminder of those golden days when the world had been so much simpler, their shared destiny so much grander. Even degraded, these old batteries represented a wealth of power and opportunity. More than Klaus had known in decades.

They also found a few of the old double harnesses. Klaus and Gretel stripped to the waist. It was awkward, but they both managed to don two harnesses, one in front and one in back. When they had finished, they both carried four batteries beneath their clothes. It was very uncomfortable.

"Let's go," he said, taking her hand.

But Gretel said, "Wait. We need something else, too." She led him down one aisle and up another, to a shelf holding a pair of jars filled with sepia-colored solution. Beside them lay an empty rucksack.

"What are those for?"

The corner of Gretel's mouth quirked up in a private little smile. "Don't worry. I've packed for you, too."

Something in the way she said it dislodged a forgotten moment from the recesses of Klaus's memory. It was the day of their capture, minutes before. He'd been away, and had rushed back to the farm to retrieve Gretel before the Communists overran the facility. He'd taken her hand, preparing to pull her through the wall, desperate to get back to the truck and drive ahead of the advancing Red Army:

"Wait," she said. She pointed at the rucksack. "We'll need that."

The sack clattered like ceramic or glass when he lifted it. "Don't worry," she said. "I've packed for you, too."

Klaus took one of the jars. A pallid, shriveled mass floated in the murk. The jar had a wide opening, and the lid had been sealed and resealed with wax. The yellowed label listed a set of dates and other annotations printed in Cyrillic, in a variety of hands and a variety of inks. The jar had last been studied six years ago. It was dusty.

He blew away some of the dust, then lifted the jar to the light, trying to peer inside. The contents settled against the glass like a dead fish.

Klaus frowned. "Is this... is this Heike's brain?"

"Part of it."

Heike. The invisible woman. Another of Doctor von Westarp's children, one of that small handful to survive the procedures and learn how to embrace the Willenskräfte. They had grown up together, lived together, trained together back at the Reichsbehörde. Until poor, fragile Heike had spent a long afternoon in private conversation with Gretel, and killed herself the next day.

The doctor didn't mourn his dead daughter. He dissected her. It was, after all, a perfect opportunity to study the physiological effects of channeling the Götterelektron. Since Heike had done that via the electrodes in her skull--like Klaus, Gretel, Reinhardt, and the others--the doctor had paid particular attention to her brain.

Gretel took the jar from his hands. She crumpled the label and tossed it aside, then picked at the wax with her fingernails. It flaked away in long clumps. Klaus caught a strong whiff of formaldehyde when she cracked the seal.

"Why..." Klaus trailed off. He tried again. "How will Heike's brain help us to escape?"

"It won't," said Gretel, as though explaining something obvious. She dumped out the contents. Formaldehyde and brain matter splattered on the floor. And then she added: "But we need a jar."

"What? I don't--"

Comprehension dawned, and something icy slithered down Klaus's spine. It became an oily nausea when it reached his gut. He put a hand over his mouth and swallowed. Oh my God.

Back during the war he had seen Gretel do strange things. Inexplicable things. Terrible things. Perhaps none more so than what she had done to Heike. Now he understood the why of it, but that only made things worse: Heike's suicide was a tiny cog in a vast machine. Gretel had prepared their escape long before they were captured. She had caused an innocent woman to kill herself, just to ensure one perfectly normal jar would be there twenty years later, exactly when and where they needed it. The sheer callousness rivaled anything ever done at the Reichsbehörde or Arzamas. But the scope of Gretel's machinations... It was a wonder Klaus's blood didn't crystallize in his veins.

Gretel was weaving cause and effect across decades. The farm had fallen because Gretel wanted it to happen. Why? It had gnawed at him since before their arrival at Arzamas. He'd asked, of course, but Gretel never answered his questions. Just smiled as she weaved her plans.

And here he was. A ghost along for the ride.

Klaus sighed. He feared this insight into his sister, but he hated Arzamas more. "What now?"

"Now you go to the bathroom."

Gott. This is getting worse and worse. "In the jar?"

Gretel frowned. Her braids--long raven-black locks streaked with gray--danced past her shoulders as she shook her head. She'd always worn her hair long, except in the early days here, when the Soviets had shaved their heads.

"No. You go," she said, pushing him toward the vault door, "to the bathroom." Another nudge toward the door, and this time she put the glassware in his hand. It was slippery. "Clean this. Leave it on the sink."

He started to talk, to ensure he understood what she said, but she interrupted him. "Go. And don't linger."

Klaus ran the water as quietly as possible, so that he could listen for footsteps in the corridor. He half suspected that part of Gretel's escape plan involved him getting caught outside the dormitory after curfew. The jar made his hands stink, and a layer of gunk had accumulated around the rim. He scrubbed it away as best he could with a towel. Working quickly, he managed to get the jar looking like it was mostly clean. And then, because the incriminating towel stank of formaldehyde (like his hands), he hid it behind one of the toilets. He balanced the jar on the narrow ledge of the sink, where a water-stained wall joined rust-stained ceramic.

When he returned to the vault, Gretel was slipping something into her blouse. "All done, brother? Time to go." She led him into the corridor.

Before it became a secret city, Arzamas-16 had been known as Sarov: a dozen churches built around the Sarova monastery, home of St. Seraphim. Everything was closed by order of the state when Sarov became a research facility. It grew quickly.

But inside and out, the architecture here was unlike most Soviet towns of comparable size: most of Arzamas-16 had been built by POW labor from Axis troops captured during the Red Army's sweep across Europe in the final months of the war. Arzamas-16 had a distinctly European, distinctly German, feel. It could have been a Thuringian village. The early days had been profoundly disorienting, when Klaus had watched the buildings going up and felt he was witnessing the destruction of the Reichsbehörde in reverse.

Arzamas-16 was a large and heavily guarded facility, ringed with walls, fences, and aggressive perimeter defenses. Including the fail-safes. This building, number three, sat near the center of town. Klaus suppressed the urge to keep looking over his shoulder while his sister led him toward the guard station.

Gretel pulled him to a stop at the base of a stairwell. They backed up a few stairs, until they perched in the shadows around the corner from the guard desk.

Klaus whispered, "The patrols--"

"There won't be any tonight." Gretel put a finger to her lips.

As Klaus's breathing slowed, he started to make out sounds from around the corner. He recognized the sound of liquid sloshing inside glass. It reminded him of poor Heike, and her ignominious end. Nothing happened for several minutes.

Then footsteps echoed up the corridor. Klaus braced for a fight he hoped to avoid. At best, he'd get a few seconds of complete insubstantiality before tripping the fail-safes, barely enough time for him and Gretel to escape through the wall.

A voice said, "What the hell are you doing?"

Another answered, "Drink with me, Sacha."

"Are you drunk?"

"I am not drunk. I am celebrating! It is, as I say this to you, not twenty minutes after midnight. Do you know what that makes today?"

The sound of glass on metal, like a bottle pulled across a desk. "Where did you get this?" That was Sacha's voice again. Klaus didn't know the guards by name, but he might have recognized their faces.

"It makes today," continued the first guard, "International Workers' Day. And so I am celebrating my hardworking brothers and sisters. To them!" A moment later, the sound of smacked lips.

"You're disgraceful, Kostya. Have you done the rounds, or must I do your job for you?"

Gretel patted Klaus on the knee when he tensed. Trust me, she mouthed.

"Disgraceful? I am a patriot, I'll have you know."

"You would drink jet fuel, if you could find it. What is that?"

"I distilled it myself." Again, the sound of a bottle being pushed across the desk. "One drink. To the workers."

A gasp. "I'm not putting that thing to my lips. Don't you ever brush your teeth? Your breath smells like shit."

"Suit yourself, Sacha."

"Not getting shot for dereliction of duty, that's what suits me."

"They don't shoot people here. They give them to the troops. Comrade Lysenko's special troops. For practice."

"I'd rather be shot."

"I'll drink to that."

A minute passed. Then: "One of us has to do the rounds. I suppose that's me, since you're hell-bent on getting shit-faced."

"No, no, I'll do the rounds. It's my service to the great Soviet Union." A wooden chair squeaked across pitted concrete. "But first I must piss. Patriotism is the only drink that stays in your blood. Vodka comes back out again. Watch the boards while I'm out."

The other guard--Sacha--sighed. "I'll watch."

Kostya's unsteady footsteps sounded louder and louder until he appeared around the corner. Klaus held his breath because he and Gretel were sitting in shadow but still easily visible to anybody who looked in their direction. His sloe-eyed sister watched the guard with something akin to dark amusement playing across her face. The guard shuffled past them without a glance.

From the direction of the bathroom, Klaus heard banging, flushing, belching, and running water.

Kostya shuffled past them again a few minutes later, jar in hand. He waved it triumphantly overhead. "Good news, Sacha!" he announced, disappearing around the corner. "I found this in the bathroom. Now you can have a drink with me."

Klaus turned to stare at his sister. She winked.

From the guard station, Sascha's voice said, "You found a jar in the bathroom? It's probably a sample jar. I'll bet somebody pissed in it."

"Nonsense. Look. Clean."

"Did you piss in it?"

"One drink. On Workers' Day."

Glass clinked against glass as somebody, probably Kostya, poured into the jar.

"Not so much. I don't want to go blind."

All Klaus could think of was formaldehyde and poor Heike's brain; the thought of imbibing from that jar nauseated him.

"To the Great Soviet." More clinking of glass.

Several moments passed in silence. And then Sacha said, "This isn't half bad."

After that there was more pouring, more toasts, and more clinking. Time passed. Gretel nudged Klaus with her elbow at one point, jerking him back to alertness. "You were going to snore," she whispered.

Klaus asked, "Do we rush them? They're both drunk."

Gretel rolled her eyes, but didn't say anything.

Not long after that, Sacha said (sounding more relaxed than he had before), "You smell like a wet dog, but you make a fine drink."

"Thank you."

"Is this really your own?"

"Yes." Kostya sounded blurry, subdued.

"How?"

Klaus understood the question. This was the most sensitive facility in the entire Soviet Union: an empire that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Even the guards were subject to scrutiny here. Klaus imagined the guards' quarters were searched almost as frequently as his own. So how did Kostya manage to distill his own vodka?

"I do it where they never look."

"They look everywhere."

"No." Kostya paused, possibly for another sip. He smacked his lips. "They never search the fail-safe chamber. Nobody likes to go down there..."

Klaus filled in the rest:... because it's full of high explosives.

The Götterelektron was the key to the superhuman feats of Doctor von Westarp's children, and their Soviet successors. But it was also their Achilles' heel. The circuitry was susceptible to a suitably crafted electromagnetic pulse. The British had designed their pixies after reverse engineering Gretel's battery, and used them with middling success during an ill-fated raid on the Reichsbehörde. Later, when the tide of war turned against the Reich, the Communists had unveiled a more potent version of the same technology.

The Arzamas fail-safe devices dwarfed the original pixies, but they worked on the same principle. They used chemical explosives to crush an electromagnet, blanketing the facility with a crippling EMP.

The bottom line being that nobody in his right mind willingly spent time near the fail-safes. An unannounced drill, a malfunction, even an escape attempt might come at any time. Death would be quick, and it would be certain.

Nobody searched the fail-safe chambers.

Sacha said, "Genius. To you."

"To me." Clink.

"Maintenance... they do that, time to time. What then? Pay them in vodka?"

"Some I could. Others would take my vodka and still sell me out. Pigs." Kostya spat. "Come. I'll show you."

Sascha belched before responding. "Into the chamber? Not going down there."

"It's safe. I've done it many times."

"You're a drunken madman." It sounded as though Sacha was making an effort not to slur his words. "I am smarter and more responsible."

"Then we'll disarm the fail-safe before we go down."

"Yes. That's a much better idea."

And then, after some discussion of whether they'd take the remainder of the bottle with them, they stumbled off to visit Kostya's still.

Gretel stood, stretched. "Well," she said. "Off we go."

Incredible, thought Klaus.

After half an hour of sneaking, hiding, dodging, and sprinting--each move dictated by the time line in Gretel's head--they stole a car. And, because the fail-safes had been disarmed, there was nothing to stop Klaus from dematerializing the car and everything in it when they reached the perimeter.

They escaped Arzamas-16 without incident, just two more ghosts in the gulag.

3 May 1963

Belgravia, London, England

Candlelight flickered through crystal wineglasses, glinted on true silverware, shimmered on fine tablecloths. The restaurant hummed with the murmur of genteel conversation punctuated by the occasional clink of fine china or pop of a wine cork.

Lady Gwendolyn Beauclerk said, "You're hopeless, William. You won't stop until you've found your way into a pauper's grave. I'm quite convinced."

Lord William Edward Guthrie Beauclerk, younger brother to the Thirteenth Duke of Aelred, squeezed his wife's hand. She laughed again.

"Pauper's grave? Never, my dear. I've left very specific instructions to be carried out on the event of my death."

"Have you?" Gwendolyn took another sip of the Chilean red. William hadn't tasted it, but the unanimous consensus at the table was that France's collectivized wineries would never produce anything approaching the South American wines.

"Oh, yes."

"You haven't mentioned this to me," said Will's brother, Aubrey.

Gwendolyn cocked her head. Her gown, royal blue silk, matched her eyes. Eyes that shone in the familiar way that meant, I'm listening.

Will paused to savor a last morsel of breaded veal. "When the time comes, darling, and I have departed from this mortal coil," said Will, "you and Aubrey shall bring my remains to the Tower Bridge. And there, from the highest parapet, you'll toss my body in the Thames."

Aubrey's face betrayed a flash of anger. "William!"

Viola Beauclerk, his horsey-faced wife, tittered behind an upraised hand. She stifled herself when the sommelier returned with another bottle to refill their glasses.

Will gently laid one hand over his unused glass. The sommelier acknowledged the gesture with a nod, sparing only the briefest glance at the stump of Will's missing finger. He whisked the glass away, looked doubly abashed: the glass ought to have been removed at the start of the meal, and he ought not to have noticed the injury. Such things were unimportant to Will, but the sommelier worked at the fringes of a social set where such lapses bordered on inexcusable.

Aubrey frowned. He waited for the sommelier to pass out of earshot before saying, "Must you talk so common at the table?"

"I'm merely reporting the facts of the matter, Your Grace." Will gestured at Gwendolyn. "You wouldn't ask me to keep secrets from my better half, would you? After all, this affects her as much as it does you. You'll be the ones carrying my body." Will patted his stomach, where the beginnings of a paunch were just visible beneath his vest. "You agreed it should be so."

"I have most certainly done nothing of the sort," said Aubrey. A quick, vocal disavowal fueled by the concern that somebody might overhear the conversation and somehow believe it to be the truth. Poor Aubrey, thought Will. Even as a child, you were humorless. I can't resist winding you up, and you know it.

Aubrey would never be capable of leaving Will's dark years entirely in the past. He'd spent too much time worrying about being seen with his younger brother, which at one time would have been social suicide. Will had come close to scuttling Aubrey's political career on more than one occasion. To this day, a sheen of anxiety--fear of embarrassment, of damaging publicity--settled over Aubrey whenever he and Will were together in public.

Will shook his head. "Oh, indeed you have. You ought to take more care when signing documents for the foundation." He winked at Gwendolyn and his sister-in-law. "An unscrupulous fellow could take advantage."

The flush of indignation crept up through the folds of fat at Aubrey's collar to his face. Quietly, he said, "It's your job to prevent exactly that sort of thing."

"Yes, it is. And you should be thankful that I am ever vigilant. Still, some things cannot be helped," said Will. He turned to Viola. "The arrangements for your husband's funeral are nothing short of scandalous. Still, it will be his final wish and by honoring it we shall honor him. Though I can't begin to speculate how we'll find so many Morris dancers on short notice."

Viola tittered again, the guilty laugh of the mildly scandalized.

Gwendolyn didn't enjoy baiting Aubrey as much as Will did. She said, "Well, then, at least it won't be a dour occasion. Let the Communists have their gray little lives." She shook her head. "Terrible."

"That's a rather unfair stereotype," said Aubrey, clearly pleased at the chance to change the subject. "They're just like us, truthfully."

Will read the subtle cues that told him Aubrey's attitude had riled her a bit. He settled back to watch. It was an old argument, but he never tired of it. Gwendolyn had no equal in verbal contretemps.

"Just like us? Forgive my ignorance, Your Grace, but I was unaware that the Kremlin had instituted a House of Lords," said Gwendolyn. "Or have you collectivized the estate at Bestwood?"

Touché, Will thought, and covered his mouth to hide a smile. Step lightly, brother.

Aubrey sidestepped the barb. "A fair point. I meant simply that the people of the Soviet Union have the same wants and needs as the rest of us. Their leaders may have different ideas about how to provide these things, but in the end we're all the same people."

"We're free to move about within the UK as we see fit. I quite suspect you'd find it a different matter if you tried to drive from Poland to Portugal. What was it Mr. Churchill once said? About the iron curtain that had been drawn around Europe?"

"Churchill was a good man for his time," said Viola, joining the discussion to support her husband. "The man we needed during the war. Nobody denies that bringing us through those years was nothing if not miraculous." Under the table, Gwendolyn squeezed Will's hand. Unaware that she had raked an old wound, Viola plunged ahead, parroting things she had heard from her husband: "But that was a different time. He had an outmoded, adversarial view of socialism. It's fortunate we're not tied to that yoke any longer."

"Well said, dear," said Aubrey. To Gwendolyn, he said, "I do agree that our cousins across the Channel are not so enlightened as we in certain areas. Which is precisely why I've sponsored several measures over the years aimed at fostering greater openness and cultural exchange between our peoples. We stand to benefit as much as they."

("Surely you mean 'comrades across the Channel,'" said Gwendolyn, sotto voce.)

"Aubrey has been pushing for such reforms since before the notion of détente was in vogue," Viola said.

"Détente? Is that what we're calling it?" said Gwendolyn. "The African situation strikes me as something of a stalemate. They support a revolution, or a workers' revolt, and we counter it by supporting the opposition."

Viola ignored her. "In fact, he was advocating for change long before the Great Famine of '42."

Aubrey shook his head. "Dreadful, that."

Gwendolyn squeezed Will's hand again. This time her soothing touch lingered, and Aubrey's disdain for open displays of affection be damned. The Great European Famine was the result of an exceptionally harsh winter. An unnatural winter. Will had been part of the team of warlocks tasked with creating that brutal weather. He'd been cut loose before the effort succeeded (more honestly, it had succeeded because he'd been tossed out), but not before he'd done wicked things for Crown and Country. Magical acts bought with blood.

Talk of the famine dredged up haunting memories, rekindled a long-smoldering guilt. Raked a wound that was always fresh, always tender. Sometimes, late at night when the memories attacked, Will couldn't meet his own eyes in the mirror.

But of course, Viola and even Aubrey were unaware of such things. There were men in Whitehall who would be quite displeased if they knew how completely Will had confided in his future wife during his long recuperation and reintroduction to civilized society. But they could go hang. Each and every one of them.

"I'd also submit," said Gwendolyn, "that the Japanese don't share your views of détente."

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere scraped against the eastern reaches of the Soviet Union like flint on steel. Border skirmishes flared where the sparks fell.

Viola shook her head knowingly. "Well, now, you simply can't reason with those people. They're not like us, you know. Brutal. Warlike. They lack the civilizing influence of a Christian faith. Twenty years of fighting!" She shuddered. "And what they did in Manchuria..."

"Speaking of cultural exchanges," said Aubrey, nudging the conversation in a direction less upsetting to his wife, "I spoke to Ambassador Fedotov today. He'll be hosting a reception next week." He raised his eyebrows, looking earnestly at both Will and Gwen. "You're available, I hope?" His smile was of the type wielded by only the wealthiest men, and only to their peers. "I give you my word the gathering won't be too terribly dour."

"Of course," said Will. "It would be a pleasure."

"Excellent. Fedotov said he looked forward to meeting you again."

Gwendolyn turned to Will. "You know the ambassador?"

Will shrugged. "We've crossed paths." Tipping his head at Aubrey, he said, "Via the foundation. Queer little fellow, the ambassador."

"I find him rather charming," said Viola.

As servers cleared away their dinner plates, Gwendolyn said to her husband, "You haven't told me about this."

Will shouldered more guilt. Not for deeds of the past, but for secrets kept in the here and now. She deserved better.

"Meeting the ambassador? It truly wasn't notable, darling. He had occasion to visit the foundation recently. It was the day of our whist tournament with Lord and Lady Albemarle, in fact. I was leaving, and in something of a state--you'll remember I was a bit tardy--"

"Yes. I remember." Gwendolyn didn't roll her eyes, instead letting the tone of her voice carry the effect.

"--and happened to encounter Aubrey and the ambassador as they came through the foundation. We exchanged niceties, that was that, and then I was out the door and somewhat manic about it."

Gwendolyn sat silently, watching Will for several moments. "Hmmm. Fascinating."

"Oh, if you haven't had a chance to enjoy his company," Viola said, "then you must attend. Do come. You'll find him delightful, Gwendolyn."

Gwendolyn smiled, just thinly enough that Viola wouldn't notice she was gritting her teeth. "I'm sure I will. I look forward to it."

Dessert was crème brûlée served with a raspberry reduction and bitter Rhodesian coffee. Will declined the coffee, ordering instead a strong Indian tea with lemon. Conversation turned to more mundane and less charged topics: race riots in the United States (disgraceful); another disruption in train service to the Midlands (disgraceful); Buckingham Palace's first color television (decadent).

The evening ended as they frequently did, with Will and Aubrey discussing foundation business at one end of the table while Gwendolyn and Viola chatted. The North Atlantic Cross-Cultural Foundation was a small, private, nongovernmental organization chartered with fostering improved relations between the United Kingdom and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Aubrey had created the foundation via permanent endowment in 1942, just in time for it to take a leading role in dealing with the flood of refugees streaming across the Channel. The flow of refugees came to an abrupt halt the following spring when the Iron Curtain slammed shut. But the foundation remained, and quickly became the place where, publicly, the British and Soviet empires intersected. Will liked to joke that he was both a lion tamer and a bear keeper. As the head of the foundation, Will worked closely with members of the Soviet diplomatic mission, their British counterparts, various members of Parliament, and occasionally the Foreign Secretary himself.

On the ride home, the London night cast dark shadows across Gwendolyn's face, interspersed with pale reflections from streetlamps shining on the white stucco houses of Belgrave Square. The interplay of light and shadow turned her blond hair white; it spun the faint dusting of gray at her temples to silver. She sighed, and tucked an errant lock behind her ear. She noticed Will watching her.

"What is it?" she asked.

"I might ask you the same," he said, smiling. She sighed a second time. "Out with it, now. Your burdens are my own, and vice versa. We had something about that in our vows, as I recall."

"Oh, Will. I'm sorry. It's just..." Her voice dropped to a whisper, so that their driver wouldn't hear her. "Your brother's wife is a vapid cow."

Will's laughter, loud and barking, startled the driver. In the rearview, his eyes briefly checked on the couple before turning back to Lyall Street. Will took Gwendolyn's hand, and he felt her tension begin to melt away as he stroked his thumb along the inside of her wrist.

"You know, there was a time when Aubrey wanted nothing more for me than to settle down with somebody like Viola."

"You'd have gone mad."

"Back then? I nearly did," he said, squeezing her hand and feeling grateful as ever that she had entered his life.

4 May 1963

Walworth, London, England

A garden shed in springtime: mud, mildew, spiders, and the stink of compost. Squalid solitude. Blessed solitude.

Raybould Marsh, formerly Lieutenant-Commander Marsh of Her Majesty's Royal Navy, and formerly of MI6, sat on a wobbly stool he'd nicked from a pub. He inspected tomato plants for bruises and fungus. He'd been taking them outside for longer periods each day and longer into the evening, acclimating them to the insult of cooler temperatures before permanently transplanting them into the garden. Done gradually enough, the transition wouldn't shock the plants.

People, thought Marsh, were much the same. Change things slowly enough, for long enough, and before you knew it, the world was warped beyond recognition.

He had expanded the shed soon after the war with materials scavenged from a disassembled Anderson shelter. The addition featured a low, sloping roof of translucent plastic, once smooth and white, now cracked and dirty by weather and age. Marsh's workbench sagged under paper sacks of potting soil, fertilizer, piles of planters. His cot stuck halfway under the bench, covered with rumpled sheets and a thin, water-stained, army-surplus blanket. A handmade bookcase, crammed with volumes of Kipling and Haggard, formed a makeshift headboard. A few old photographs had been pinned to the shelves, their edges yellowed and curled.

The clatter of a broken dish echoed from the house. Liv, his wife, raised her voice in shrill alarm. Marsh reached behind the plants and clicked on the wireless.

He didn't particularly care for the news or the state of the world, but it did drown out the noise. Running electrical mains to the shed had been something of a job, but necessary for preserving his sanity. Sometimes, when the clamor from the house became too much, he'd tune the radio between stations as a white noise generator.

The small of Marsh's back twinged when he leaned over to inspect another plant. Pain flared in his knee, too. The problem in his knee was an old one, something he'd had even as a young man. It came and went over the years. The pain in his back was a souvenir of age.

The odor of hot earth wafted through the shed. As the valves in the wireless heated up, they scorched away the fine layer of dust that had settled through the grille. Static became an ethereal warble laced with the suggestion of human voices. The amplifiers stabilized, and the voices became a Russian choir. Most stations on the Continent sounded like this when they weren't spreading the latest propaganda from Moscow. Sometimes, when he could stomach it, he listened to those broadcasts. They reminded him of desperate days from long ago. Days spent studying maps, conferring with warlocks, hoping to entice the Soviets to finish off the Third Reich.

Marsh gave the tuner dial a few flicks of his thumb. It landed on something loud and discordant--modern music played by a group out of Liverpool. Another flick brought him to a BBC station playing more familiar music. Marsh recognized the Benny Goodman recording, and remembered when it had been new. The big band hour was popular among people old enough to remember life before the war.

He listened to the remainder of the program while mending a leaky hose with bit of inner tube cut from a bicycle tire. The hose was a motley thing, riddled with patches down its length, but Marsh had kept it working long past its useful life. They might have scraped together enough money to afford the extravagance of a new hose, but Marsh never suggested this to Liv. A new hose would have meant fewer excuses to spend time in the shed. Meant cutting off another avenue of escape.

They'd purchased the bicycle for their newborn son, John, in happy anticipation of the day he'd be old enough to use it. It still leaned behind the shed, unused, rusting into nothing.

Vera Lynn sang wistfully of bluebirds and white cliffs. Liv used to sing the same song, better than Lynn herself. But she hadn't sung in the house since John was born.

Marsh made to change the station again, but the song ended before he could get his hands free, and then it was the top of the hour and time for the news. That morning's moon shot was the lead story. Three cosmonauts had departed the space station; in a few days' time, they would become the first men to see the far side of the moon with their own eyes. Von Braun was sure to receive the Order of Lenin upon their safe return. Predictably, President Nixon had sent effusive congratulations to Khrushchev on behalf of the American people. In the Near East, the Royal Navy had stationed the carrier HMS Ocean into the Persian Gulf, near British Petroleum's Abadan refinery in southern Iran, in response to increased Soviet activity along the borders of the Azerbaijan and Turkmen SSR. Elsewhere, scattered and confusing reports had trickled in to the BBC bureau in Cape Town, including rumors of abandoned villages in the Tanganyika Territory. Closer to home, foresters investigated a recent fire that had burned acres of woodland in Gloucestershire.

Outside, the kitchen door creaked and slammed. Marsh sighed. He flicked off the wireless.

Liv barged in a few moments later, rattling the tools hung behind the door. She stank of antiseptic and watered-down perfume. Marsh saw the bags beneath her eyes, darker than usual, and decided not to mention it. John had had one of his bad nights.

The wrinkles in the hollows of her cheeks creased into the edges of a frown. "Were you planning to spend the entire day out here?"

"I'm nearly finished."

Liv pursed her lips. "Nearly finished," she muttered. "You always say that."

"The sooner I get these in the ground, the sooner we can have a decent salad again." Marsh cringed inwardly as soon as the words passed his lips.

"Decent," she said. "As opposed to the indecent meals that I prepare the rest of the year."

Marsh wondered, as he sometimes did, about the passage of time. The years had transformed Liv's freckles, once so endearing and erotic, into age spots that repulsed him. How had things gone so terribly wrong? Time was a cruel alchemist.

"Don't, Liv. You know what I meant." She carried her handbag, he noticed. And she'd done her lips. Liv hadn't bothered in years, but she'd begun again recently. It meant she'd come home late, smelling of another man's aftershave and not respecting Marsh enough to hide it. "Where are you going?" he asked.

"Out," she said. Somehow, the plants didn't shrivel and blacken before the naked contempt in her voice. But Liv never missed her mark, never missed a chance to make him feel useless. Emasculated.

She flung something across the cramped shed. A ring of keys clattered on his workbench, knocking a large chip from a terra-cotta planter. "Feed your son." Over her shoulder as she walked away, she added, "It's your turn."

He waited in the shed until he heard the screeching of the garden gate. It banged shut behind Liv; he made a mental note to oil the hinges and replace the spring. Her heels clicked on the pavement outside, and then faded into the general low-level thrum of the neighborhood.

Marsh considered finishing with the tomatoes before going inside, but rejected the idea. John had to eat.

The house was quiet, but for the simmering of a pot Liv had prepared: barley soup with peas, carrots, and a bit of beef. Marsh filled a bowl, grabbed a towel, and went upstairs. The stairs creaked. John launched into a new round of keening.

John's room was down a short hallway from the bedroom his parents ostensibly shared. Marsh fished out the key ring with one hand while balancing the bowl in the other. Four keys hung from the ring. John paused when Marsh scratched the first key into the first lock. Marsh noticed a puddle beneath the door when he worked his way to the final and lowest lock.

He braced himself before turning the last bolt. Sometimes John ran, blind and mindless. But his son didn't rush the door. Shards of crockery splintered beneath the soles of Marsh's work boots when he entered. John had flung a bowl of soup across the room.

The room stank. The door behind Marsh was splattered with brown stains. John had flung other things at Liv, too. No wonder she'd left for the day.

Marsh turned on the light. Every wall had been covered with calico, and stuffed with carpet scraps, horsehair, and newspaper. Homemade soundproofing, the best Marsh could manage. In places, where the insulation was torn, he could glimpse the original robin's egg blue walls. The paint was a holdover from those last giddy days, when they'd done up the nursery in the final weeks of Liv's pregnancy. Before they'd taken John home from the hospital; before they'd discovered something wrong with their son.

That was the doctors' term. Wrong. Because they didn't know what else to call it.

Everything he'd done, everything they'd endured, all for naught. Ruined by a fluke of fate.

Yellowing placards lined the walls near the ceiling, displaying the letters of the alphabet. Those were leftovers from the period before they realized the extent of the problem, when Liv had thought she might be able to homeschool their son.

John himself huddled in his usual corner, naked. They'd given up trying to clothe him after he'd grown large enough to overpower Liv. He clenched his knees to his chest, rocking sideways and knocking his head against the wall with a steady, monotonous rhythm. That was another reason for the padding. John could do that for hours, even days, unless somebody moved him.

"It's me, son," said Marsh. "Your father."

Sometimes--on good days--John paused in his rocking, ever so briefly, when Marsh entered. A token acknowledgment, a hint of connection. But not today. John kept batting his head against the wall without interruption. Marsh had recently replaced the padding there.

"I brought something to eat."

Pat, pat, pat, pat, pat.

Marsh hunkered down next to John, cross-legged, ignoring the protests from his knee. John's rocking wafted the scent of his unwashed body at his father; he smelled faintly of sour milk. It took two people to bathe him, but Marsh and Liv rarely stayed in the same room together.

"I see you gave your mum some trouble today. You shouldn't be so difficult to her."

Pat, pat, pat, pat.

"She loves you as much as I do."

Pat, pat, pat.

Marsh sighed. "Let's get some food in you, son." He laid his hand on John's shoulder.

John rolled his head toward Marsh, turning a pair of colorless eyes at him. It always unnerved Marsh when he did that, just as much as it cut him with slivers of irrational hope. He knew those eyes were sightless, equally devoid of function as of warmth.

John sniffed the air. He leaned toward Marsh, snuffling with a machine gun burst of quick, sharp inhalations. Marsh held his free hand toward John's face, so that his son could get the scent. Then he did the same with the soup.

John's mouth fell open. But before Marsh could get the spoon in, his son began to wail: a single, unbroken note that lasted as long as the air in his lungs.

He did it again. And again. And again.

Copyright © 2012 by Ian Tregillis

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details